Some Sunlight Seeps In

In relation to transparency in the Financial Remedies Court (FRC) there are further signs that the tectonic plates are shifting.[[1]]

BT v CU

In November 2021, Mostyn J set the cat among the pigeons with his judgments in BT v CU [2021] EWFC 87, [2022] 1 WLR 1349, [100]–[114], and, four days later, in A v M [2021] EWFC 89, [101]–[106].

The headline message was clear and unequivocal (A v M, [104]):

‘In step with the modern recognition of the vital public importance of transparency, my default position for the future will be to publish my financial remedy judgments in full without anonymisation, save as to the identity of children. Derogations from that default position will have to be distinctly justified.’

‘Justified’, that is, as spelt out in BT v CU, [113], ‘by reference to specific facts, rather than by reliance on generalisations’.

Mostyn J explained his thinking (BT v CU, [103]–[105]) as follows:

‘103. … I accept that the current convention is that a judgment on a financial remedy application should be anonymised, although the decision whether to do so reposes in the discretion of the individual judge. Mr Chandler has cited the judgment of Stanley Burnton LJ in Lykiardopulo v Lykiardopulo [2011] 1 FLR 1427, para 79 where anonymisation is described as the “general practice” justified by reference to respect for the parties’ private lives, the promotion of full and frank disclosure, and because the main information is provided under compulsion.

104. The move to transparency has questioned the logic of this secrecy. Almost all civil litigation requires candid and truthful disclosure, given under compulsion. The recently extended CPR PD51U – Disclosure Pilot for the Business and Property Courts – contains intricate and detailed compulsory disclosure obligations. Para 3.1(5) requires parties “to act honestly in relation to the process of giving disclosure”. Many types of civil litigation involve intrusion into the parties’ private lives. Yet judgments in those cases are almost invariably given without anonymisation.

105. I no longer hold the view that financial remedy proceedings are a special class of civil litigation justifying a veil of secrecy being thrown over the details of the case in the court’s judgment. In my opinion it is another example of the Family Court occupying a legal Alsatia (Richardson v Richardson [2011] EWCA Civ 79, [2011] 2 FLR 244, para 53, per Munby LJ) or a desert island “in which general legal concepts are suspended or mean something different” (Prest v Petrodel Resources Ltd and others [2013] UKSC 34, [2013] 2 AC 415, para 37, per Lord Sumption).’

He went on ([109]): ‘it is time for [the convention] to be abandoned’.

Mostyn J bolstered the argument by pointing out ([106]–[108]) the practice in relation to appeal judgments, whether the appeal is to a High Court Judge or to the Court of Appeal, of granting anonymity in such judgments only in rare cases where the specific facts warrant it. This, as he pointed out, makes ‘secrecy … even more difficult to defend’, indeed, ‘impossible to defend’.

A v M

In A v M, [105]–[106], Mostyn J elaborated his reasoning:

‘105. There seems to have been a certain amount of surprise caused by my decision in BT v CU to abandon anonymisation of my future financial remedy judgments. Views have been expressed that I have snatched away an established right to anonymity in such judgments. This is not so. I do not believe that there is any such right. My personal research tells me that before the 1939–1945 War, and indeed until much more recently, there was no anonymity in the Probate Divorce and Admiralty Division (“PDA”), children and nullity cases apart, and even then only sometimes. For example, there is no example after 1858 of a first instance judgment in a variation of settlement case being published anonymously until as late as 2005 when N v N and F Trust [2005] EWHC 2908 (Fam), [2006] 1 FLR 856 was reported in that form. Even in nullity cases a general rule that they should be heard in camera was unlawful: Scott v Scott [1913] AC 417, HL. That case, far from being a paean to PDA exceptionality, is, in truth, precisely the contrary. It is a clear statement (to adopt modern metaphors) that the PDA was neither Alsatia nor a desert island: see Earl Loreburn at 447, where he succinctly stated:“the Divorce Court is bound by the general rule of publicity applicable to the High Court and subject to the same exception.”

See also, to the same effect, Viscount Haldane LC at 434, 436; Earl of Halsbury at 443; Lord Atkinson at 462–463; and Lord Shaw of Dunfermline at 469, 475 and 478–480.

106. It is therefore difficult to understand how the practice arose of routinely anonymising ancillary relief judgments given in the Family Division (the successor to the PDA) or in the Family Court proceeding at High Court judge level. So far as I can tell, it is traceable back to the provisions in the Matrimonial Causes Rules (“MCR”) that made the Registrar the usual first instance judge – see for example rule 77(1) of the 1973 rules which stated that “on or after the filing of a notice in Form 11 or 13 an appointment shall be fixed for the hearing of the application by the Registrar.” The Registrar always sat in chambers. Rule 78(2) allowed an application to be referred to a judge, and rule 82(2) provided that the hearing of a referred matter “shall, unless otherwise directed, take place in chambers.” I believe that the earlier versions of the MCR said the same. It is to this banal provision that all the secrecy that has surrounded financial remedy judgments can probably be traced, although routine anonymisation of first instance judgments does not seem to have taken hold until the 1990s. So far as I can tell, the practice of anonymising judgments given by High Court judges is explicable only by reference to the hearing having been in chambers and behind closed doors. But that of itself would not explain the adoption of the practice as a chambers judgment is not secret and is publishable whether or not anonymised: see Clibbery v Allan and Another [2001] 2 FLR 819 at [24]–[33], [74], [117]–[118] and [150]. I have not been able to discover any statement of practice made at any time before Thorpe LJ’s judgment in Lykiardopulo v Lykiardopulo [2010] EWCA Civ 1315, [2011] 1 FLR 1427 (at [45] and [79][[2]]]) explaining, let alone justifying, the convention (whenever it arose) of routinely anonymising almost all ancillary relief judgments given by High Court judges. That convention is very hard, if not impossible, to square with the true message of Scott v Scott which is that the Family Courts are not a desert island.’

On 16 November 2021, I published a comment on all this under the title More Transparency in the Financial Remedies Court. I wrote:

‘It seems to me, if I may be permitted to say so, that Mostyn J is entirely correct, in his history, in his analysis and in his conclusion. His judgments in these two cases should be welcomed, accepted and applied by all.’

I observed that one commentator had pointed out that the reasoning in BT v CU and A v M is the complete opposite of what the same judge had previously said in W v M (TOLATA Proceedings: Anonymity) [2012] EWHC 1679 (Fam), [2013] 1 FLR 1513, and then in DL v SL (Financial Remedy Proceedings: Privacy) [2015] EWHC 2621 (Fam), [2016] 2 FLR 552 (and, I add, in Appleton and Gallagher v News Group Newspapers and PA [2015] EWHC 2689 (Fam), [2016] 2 FLR 1). However, as I went on:

‘The issue is not that Mostyn J has changed his mind about anonymisation of judgments – as he explicitly accepts that he has: BT v CU, para 105. A judge is always entitled to revise his earlier thinking, not least to take account of changes and developments in the legal landscape. The question, put starkly, is whether he was right then, and is wrong now, or whether he was wrong then and is right now. We should all agree that, whatever his earlier thinking, Mostyn J has provided clear and compelling justification for his most recent views, views which, I suggest, are well founded in both history and principle. He is, if you like, recanting old heresy rather than descending into new heresy.’

I asked rhetorically, What are the objections? In substance, I said, there seemed to be two: ‘first, that cases in the FRC involve private and sensitive matters which properly justify the anonymisation of the parties; secondly, that such cases involve massive and ongoing compulsory disclosure’. Neither contention, I went on to argue, was convincing.

I threw down a challenge:

‘Those who wish to controvert what Mostyn J is now saying must do so by addressing the detail of what he is saying … and then coming up with an equally compelling counter-argument; an argument based on principle and not on a sentimental attachment to an allegedly established practice which is, in truth, of surprisingly recent origin.’

So far as I am aware, no one has risen to the challenge.

Xanthopoulos v Rakshina

Now, on 12 April 2022, Mostyn J has returned to the issue, with a masterly judgment which, while staying with the historical and analytical fundamentals of BT v CU and A v M, provides much more of the detail underpinning his reasoning and a richer and more profound analysis: Xanthopoulos v Rakshina [2022] EWFC 30, [74]–[141]. His judgment deserves to be read in full, so I eschew summary.

Suffice it to note that he gives us in turn: an extended treatment of the procedural history touched on in A v M, [106] ([77]–[88]); a fine encomium for the extraordinary dissenting judgment of Fletcher Moulton LJ in the Court of Appeal in Scott v Scott [1912] P 241 ([89]–[90]); compelling disquisitions on the true meaning of section 12 of the Administration of Justice Act 1960 ([91]–[93]), on the meaning and effect of the standard rubric ([94]–[97]), on the important judgment of Lord Woolf MR in Hodgson v Imperial Tobacco Ltd [1998] 1 WLR 1056 ([98]–[100]), and on anonymity orders ([101]–[106]); a devastating analysis of Clibbery v Allan [2002] EWCA Civ 45, [2002] Fam 261, observing that the opinions of Dame Elizabeth Butler-Sloss P and Thorpe LJ on the key point were obiter, that their reasoning ‘stood on a very shaky foundation’, and that they had in any event been overtaken by the rule changes in 2009 which entitled journalists to attend hearings in chambers ([107]–[116]); and an interesting discussion of the consequences of the introduction of the standard Family Division judgment template in about 2002 ([117]–[118]). At that point in the analysis, he provides this summary ([119]–[121]):

‘119. In my opinion, for the reasons set out above, in a financial remedy case heard in private, which does not fall within section 12(1)(a) of the 1960 Act, the standard rubric is completely ineffective to prevent full reporting of the proceedings or of the judgment ...

120. For the reasons I have stated above, the justification identified in Clibbery v Allan for having a blanket ban on the full reporting of proceedings heard in private disappeared with the 2009 rule change.

121. Therefore it follows that anonymisation can only be imposed by the court making a specific anonymity order in the individual case. Such an order can only lawfully be made following the carrying out of the ultimate balancing test referred to by Lord Steyn in Re S. It cannot be made casually or off-the-cuff, and it certainly cannot be made systematically by a rubric. On the contrary, the default condition or starting point should be open justice, and open justice means that litigants should be named in any judgment, even if it is painful and humiliating for them, as Lord Atkinson recognised in Scott v Scott.’

He concludes with references to In re Guardian News and Media Ltd & Ors [2010] UKSC 1, [2010] 2 AC 697 ([122]); to the Practice Guidance I had issued as President on 16 January 2014, Transparency in The Family Courts: Publication of Judgments, paras 18–20 of which he subjects to what I have to confess is pointed and well-merited criticism ([123]–[124]); and then to the Consultation Papers issued by the President on 29 October 2021 and by the FRC lead judges, Mostyn J and HHJ Hess, on 28 October 2021 ([125]–[127]). He identifies the fallacy in posing the question in the form ‘Why is it in the public interest that the parties should be named?’ rather than, as it should be, in the form ‘Why is it in the public interest that the parties should be anonymous?’ ([128]). He has interesting and important things to say about the Judicial Proceedings (Regulation of Reports) Act 1926 ([129]–[134]), before explaining why on the facts of the case he has decided not to anonymise the names of the parties, while restraining the naming of their children ([135]–[139]). His final observations merit quotation in full ([140]–[141]):

‘140. My fundamental conclusion is that, irrespective of the terms of the standard rubric, section 12(1) of the 1960 Act, following long established principles, permits a financial remedy judgment (which is not mainly about child maintenance) to be fully reported without anonymity unless the court has made a reporting restriction order following a Re S balancing exercise. In my opinion this freedom can only be restricted by primary legislation and not by rules of court. Section 12(4) of the 1960 Act states that:“Nothing in this section shall be construed as implying that any publication is punishable as contempt of court which would not be so punishable apart from this section (and in particular where the publication is not so punishable by reason of being authorised by rules of court).”

The power of the Family Procedure Rule Committee to make rules under this subsection is strictly confined to making something presently punishable as contempt not so punishable. It cannot make rules the other way round to make punishable as contempt something that is not presently so punishable. Therefore, any change to make financial remedy judgments systematically anonymous has to be done by primary legislation.’

Having fired this shot across their bows, he adds:

‘141. I accept and understand that the question of open justice in financial remedy cases is a matter of some controversy on which views are far from unanimous. I express the hope that the Financial Remedies Court Transparency Group (a sub-group of the Family Transparency Implementation Group) will consider carefully the legal issues raised in this judgment.’

Consistently with his reasoning, the rubric attached by Mostyn J to the judgment is in the following terms:

‘This judgment was delivered in private. The judge hereby gives permission – if permission is needed – for it to be published. The judge has made a reporting restriction order which provides that in no report of, or commentary on, the proceedings or this judgment may the children be named or their schools or address identified. Failure to comply with that order will be a contempt of court.’

In Xanthopoulos v Rakshina, Mostyn J has delivered a judgment of tremendous range and power; a masterly and, at the end of the day, compelling demolition of commonly held but in truth, as he demonstrates, fundamentally flawed conceptions; and a judgment in which, I would respectfully urge, like its two predecessors, he is entirely correct, in his history, in his analysis and in his conclusion. His latest judgment, like the previous two, should be welcomed, accepted and applied by all.

I repeat my earlier challenge:

‘Those who wish to controvert what Mostyn J is now saying must do so by addressing the detail of what he is saying … and then coming up with an equally compelling counter-argument; an argument based on principle and not on a sentimental attachment to an allegedly established practice which is, in truth, of surprisingly recent origin.’

Is there no one willing to take up the gage?

It has been suggested by the commentariat that Mostyn J violated the rule of stare decisis in changing his mind. This is not so. He was not bound by his previous view. High Court judges are not technically bound by decisions of their peers, but they should generally follow a decision of a court of co-ordinate jurisdiction unless there is a powerful reason for not doing so: Willers v Joyce & Anor (No 2) [2016] UKSC 44, [2018] AC 843, [9]. Mostyn J clearly articulates powerful reasons for not adhering to his previous view, of which the foremost is that he now acknowledges it as fundamentally erroneous.

In the meantime, I venture to suggest that, despite the detail of the judgment, there is room for some additional exploration of these important issues, elaborating some of what Mostyn J has said and even, if he will forgive me, filling in a few gaps. I do not seek to challenge his conclusions, merely to add some additional support for his arguments.

Scott v Scott

I start with the great case of Scott (Otherwise Morgan) v Scott [1912] P 4, [1912] P 241, [1913] AC 417. The facts were simple. A wife petitioned for nullity on the ground of her husband’s impotence. The Registrar made an order in common form that ‘this cause be heard in camera’. At the trial before Sir Samuel Evans P, the suit was undefended, the husband having withdrawn his defence. The judge granted the wife a decree nisi. Subsequently, on her instructions, the wife’s solicitor obtained an official transcript of the hearing, of which copies were sent to the husband’s father, to a sister of the husband and to ‘an intimate friend’ of the wife. Her purpose was ‘in defence of her reputation’ and in response to allegations by the husband ‘reflecting on her sanity’. Bargrave Deane J held that this was a contempt of court.

On appeal by the wife to the Court of Appeal and further appeal to the House of Lords, there were three issues: (1) Did the court have jurisdiction to make the order that the case be heard in camera? (2) If so, did the order made by the Registrar prevent the subsequent publication of the proceedings? (3) Was the order made by Bargrave Deane J in a ‘criminal cause or matter’ so as to preclude any appeal to the Court of Appeal?

The full Court of Appeal by a majority (Cozens-Hardy MR, Farwell, Buckley and Kennedy LJJ, Vaughan-Williams and Fletcher Moulton LJJ dissenting) answered all three questions in the affirmative and dismissed the appeal.[[3]] The House of Lords (Viscount Haldane LC, the Earl of Halsbury, Earl Loreburn, Lord Atkinson and Lord Shaw of Dunfermline) unanimously allowed the appeal, answering all three questions in the negative.

We are all familiar with the ringing statements of the high constitutional importance of open justice which are to be found in Scott v Scott; in particular, in the dissenting judgment of Fletcher Moulton LJ[[4]] in the Court of Appeal (vitally important as foreshadowing so much of what was later to be said in the House of Lords) and in the famous speech of Lord Shaw of Dunfermline in the House of Lords. These are two great judicial declarations which ring down the ages. But for present purposes a narrower focus is sufficient.

In relation to what is now the Family Division, the case is of importance – great, and continuing, importance – for two reasons.

First, it established definitively and for all time that, as Viscount Haldane LC put it ([1913] AC 417, 436), referring to the Court for Divorce and Matrimonial Causes established by the Matrimonial Causes Act 1857:

‘the Court which the statute constituted is a new Court governed by the same principles, so far as publicity is concerned, as govern other Courts.’

Earl Loreburn was equally pithy (447):

‘the Divorce Court is bound by the general rule of publicity applicable to the High Court.’

Specifically, it followed that, specific statutory provisions apart, the Divorce Court and its successors could, and can, sit in camera only in the very limited circumstances permissible in the other Divisions.

As I put it in Re Webster, Norfolk County Council v Webster [2006] EWHC 2733 (Fam), [2007] 1 FLR 1146, [39]:

‘Scott v Scott established once and for all that there is in principle no difference for these purposes between the Family Division and the other two Divisions. It is impossible to argue that the Family Division as such has any greater powers to sit in secret or to enforce the confidentiality of its proceedings than any other part of the High Court. If it is to be argued that the Family Division has some such power, either generally or in some particular class or classes of case, that power is not to be derived from the fact that the Family Division is the Family Division or from any “practice” of the Family Division however inveterate; it has to be founded in specific statutory authority or, since the coming into force of the Human Rights Act 1998, justified by reference to the Convention.’

Scott v Scott demonstrated the astonishing fact that in a succession of cases between 1869 and 1903 the practice exemplified by the Registrar’s order had grown up in disregard – one is tempted to say defiance – not merely of section 46 of the 1857 Act, which provided that ‘the witnesses in all proceedings before the court … shall be sworn and examined orally in open court’, but also of the definitive judgment of Bramwell B sitting in the Full Court in H (Falsely Called C) v C (1859) 29 LJ(P&M) 29, 1 Sw & Tr 605.

Lord Shaw of Dunfermline was scathing in his indictment of what had been allowed to happen ([1913] AC 417, 478–479):

‘I think it would have been better had those attempts to evade the publicity commanded by the statute then ceased and the judgment of Bramwell B been accepted as law.’

Having referred to what Sir James Hannen JO had said in A v A (1875) LR 3 P&M 230, he continued:

‘I must say … that, accepting this as historically accurate, it appears to me to be a confession of a progressive departure from the law. No doubt it bound the learned judge, but it is an illustration of … the liability, unless the most rigorous vigilance is practised, to have constitutional rights, and even the imperative of Parliament, whittled away by the practice of the judiciary.’

It might be thought that these magisterial pronouncements (and there is much else in Scott v Scott to similar effect) would have put an end, once and for all, to the idea that in some mysterious and unexplained fashion the Divorce Court and its successors the Probate Divorce and Admiralty Division and the Family Division are not bound by the same principles as the rest of the High Court. Not a bit of it. One hundred years on and the heresy is still with us. As I had to lament as recently as 2018 in Kerman v Akhmedova [2018] EWCA Civ 307, [2018] 2 FLR 354, [20]–[22]:

‘20. Mr Shepherd was … on much firmer ground when he asked rhetorically, “Whether the Family Court is to be permitted to adopt different trial and post trial procedures to those permitted by other divisions of the High Court.” As a matter of generality, the answer to this is, and must be, an emphatic NO!

21. It is the best part of sixty years since Vaisey J explained in In re Hastings (No 3) [1959] Ch 368 that “there is now only one court – the High Court of Justice.” It is now eleven years since I observed in A v A [2007] EWHC 99 (Fam), [2007] 2 FLR 467, paras 19, 21 (though, of course, at the time I was a mere puisne), that “the [Family Division cannot] simply ride roughshod over established principle” and that “the relevant legal principles which have to be applied are precisely the same in this division as in the other two divisions.” In Richardson v Richardson [2011] EWCA Civ 79, [2011] 2 FLR 244, para 53, we said that, “The Family Division is part of the High Court. It is not some legal Alsatia where the common law and equity do not apply.” And in Prest v Petrodel Resources Ltd and others [2013] UKSC 34, [2013] 2 AC 415, para 37, Lord Sumption JSC observed that “Courts exercising family jurisdiction do not occupy a desert island in which general legal concepts are suspended or mean something different.”

22. It is time to give this canard its final quietus. Let it be said and understood, once and for all: the legal principles – whether principles of the common law or principles of equity – which have to be applied in the Family Division (and, for that matter, also, of course, in the Family Court) are precisely the same as in the Chancery Division, the Queen’s Bench Division and the County Court.’

I note, before passing on, that the House of Lords in Scott v Scott recognised three so-called exceptions to the principle of open justice: cases involving children, cases involving lunatics and cases relating to secret processes. None, as will be appreciated, has any bearing on the point with which we are here concerned.

The second point to be derived from Scott v Scott was the definitive statement that it is not, as such, a contempt of court to publish an account of what has gone on in chambers or to publish a judgment delivered in chambers. According to Bargrave Deane J ([1912] P 4, 6–7):

‘It is gross contempt of Court to report anything heard in camera. It is the same even in regard to reporting summonses heard in chambers, or in Court as in chambers, which is, in effect, the same thing, unless by special leave of the judge.’[[5]]

Fletcher Moulton LJ, in his great dissenting judgment, later vindicated in the House of Lords, was pitiless in his demolition of Bargrave Deane J’s intellectually lazy and simplistic decision ([1912] P 241, 271–272):

‘The language of the order provides for privacy at the hearing. It has nothing to do with secrecy as to the facts of the case. The learned judge interprets it as enjoining such secrecy. He realizes that having done so he is logically compelled to put all hearings in chambers on the same footing, and he therefore declares that under the procedure of our Courts there is an absolute obligation to perpetual secrecy as to what passes at the hearing of all summonses in chambers. No one has ventured to say before us a single word in defence of this part of the judgment. It is not too much to say that it is ludicrously at variance with the actual practice. Many thousands of summonses in actions are heard in chambers in the course of each year, and during all my experience at the Bar and on the Bench I have never heard it suggested that there is the slightest obligation of secrecy as to what passes in chambers. Everything which there transpires is and always has been spoken of with precisely the same freedom as that which passes in Court. Yet, as the judge acknowledges, the phrases “in camera” and “in chambers” are synonymous. We start, therefore, from the datum line that the judgment which we are asked to declare unappealable is confessedly based on reasoning which makes the whole lives of those who are professionally engaged in litigation one long series of criminal contempts of Court.’

He went on (275):

‘conclusive proof that the order cannot bear the interpretation contended for by the respondent is derived from an examination of the origin of such orders and the jurisdiction under which they are made. The result of such an examination is in my opinion to establish beyond doubt that the order that the case should be heard in camera has always been intended to relate and has in fact related to the mode of conducting the hearing and to nothing more.’

Ever since then, the law has been quite clear, and it applies as much to the Family Division as to any other part of the High Court. In the absence of any relevant restriction imposed by statute it is not a contempt of court to publish or report a judgment, whether in whole or in part, merely because it was given or handed down in private – in chambers – and not in open court: Forbes v Smith [1998] 1 All ER 973 and Hodgson & Ors v Imperial Tobacco Ltd & Ors [1998] 1 WLR 1056.

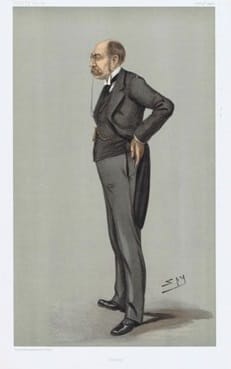

Fletcher Moulton (1844–1921): mathematician, barrister, MP, appeal court judge and Law Lord. He was at one point judged to be one of the twelve most intelligent men in the United Kingdom. During the Great War he served as Director-General of the Explosives Department.

Proceedings heard in chambers

Mostyn J in In Xanthopoulos v Rakshina, [98], has set out in full what he rightly describes as the ‘vitally important synopsis of the status of proceedings heard in chambers’ provided by Lord Woolf MR in Hodgson v Imperial Tobacco Ltd [1998] 1 WLR 1056, 1071, a synopsis which he said, and I agree, ‘stands in completely conformity with the judgment of Fletcher Moulton LJ’. I repeat the key propositions:

‘(1) The public has no right to attend hearings in chambers because of the nature of the work transacted in chambers … (2) What happens during the proceedings in chambers is not confidential or secret and information about what occurs in chambers and the judgment or order pronounced can, and in the case of any judgment or order should, be made available to the public when requested. (3) …. (4) To disclose what occurs in chambers does not constitute a breach of confidence or amount to contempt as long as any comment which is made does not substantially prejudice the administration of justice. (5) The position summarised above does not apply to the exceptional situations identified in s12(1) of the Act of 1960 or where the court, with the power to do so, orders otherwise.’

Exactly the same principle applies in the Family Division: Clibbery v Allan [2002] EWCA Civ 45, [2002] Fam 261.

The litigant’s right to speak about their case

Before proceeding further there is another crucially important point emphasised by Fletcher Moulton LJ in a key passage ([1912] P 241, 272–274) which is too long to quote but requires to be read in full. Mostyn J has set it all out in Xanthopoulos v Rakshina, [89], so I shall be selective. Fletcher Moulton LJ first explains that:

‘Civil Courts exist solely to enforce the rights or redress the wrongs of those who appeal to them and for no other purpose. They have ample powers for so doing. They summon the defendant to come before them, they give both parties assistance in obtaining the necessary evidence, they hear the rival contentions, and finally they decree the appropriate relief if any. But they can do no more except that when called upon to do so they enforce the relief that they have granted. Beyond and besides this the Court acquires no power or jurisdiction over an individual by reason of his having become a litigant. He remains in all other respects as free and as independent of interference from the Court as he was before the suit was instituted or as any other member of the public is who has never been a litigant.’

Postulating a nullity suit in which the defendant has been successful, he continues:

‘He was brought into the suit by no act of his own, but by the summons of the Court. He has been present at the hearing not by bargain with the judge, but of right. And now it has been declared that the charges were unfounded. In virtue of what authority can the judge control the future actions of that man and say that he shall never speak of that which has passed at the hearing, including of course the oral judgment pronounced by the judge? How has that defendant surrendered or forfeited any part of his personal freedom of action? He is sui juris and remains so, and the fact of his having been compelled to be a litigant cannot put him for all time in the position of being in statu pupillari to the judge before whom the cause has come, so that such judge can impose upon him his personal views as to propriety or duty.’

He then adds an important point which, as we will see, has its resonance in the modern jurisprudence of the Human Rights Act 1998:

‘it is often not merely a solace but a duty which a man owes to himself and to those about him to inform them fully of all that has passed in these inexpressibly painful cases. It may be vital to him to clear away misconception in the minds of those who are dear to him or whose good opinion he values, and to obtain from them the sympathy and support that he needs.’

Turning to the converse situation he continues:

‘the argument is equally strong in the case of the petitioner. She comes before the Court as of right to obtain its aid in enforcing her rights. In accepting that aid she no more relinquishes her personal freedom of action than does the defendant in entering an appearance. The Court can impose no terms as a condition of its rendering its aid to parties in the enforcement of their claims. They have the right to demand that aid of the Court and it is there to give it without conditions. The same considerations apply to a defendant who is unsuccessful. The Court has the right and the duty to decree the proper relief against him, but it can do no more. It cannot add to that relief directions or commands as to his future conduct. If they are not part of the relief itself they are pronounced without authority.’

He comes to his exordium:

‘The magnitude of the danger is illustrated by the present case. The serious encroachment on personal liberty which is here proposed is not supported by a single decision. There is on record no case where the Courts have asserted a right to control the personal acts of litigants after the conclusion of the suit except to enforce the relief granted. Yet without the support of any precedent the learned judge has in this case arrogated to judges the power to do so and we are asked to support him. The nature of the encroachment emphasizes the warning. Most people feel that the unrestricted publication in newspapers of what passes at the hearing of certain types of cases is a great evil, and many proposals have been made for regulating it. But all agree that this must be done by the Legislature. The judges are not the tribunal to decide on the proper limitations of public rights. The order in the present case is an attempt to assert for judges indefinitely wide powers in this respect. Not even the strongest partisan of legislative action has ventured to propose that private communications between individuals as to that which passes at the hearing of a suit should be interfered with. This order proceeds on the basis that a judge can of his own initiative absolutely forbid them.’

Now that, of course, was said in a dissenting judgment, albeit one which received the approbation of the House of Lords. But the same views as those expressed by Fletcher Moulton LJ are to be found also in the speeches in the House of Lords of the Earl of Halsbury ([1913] AC 417, 441) and Earl Loreburn (449), who expressly associated themselves with the Lord Justice,[[6]] and of Lord Shaw of Dunfermline. Lord Shaw in striking language (483) denied the right of the judges to require a litigant to ‘remain perpetually silent’ and (484) denounced Bargrave Deane J’s order as ‘an exercise of judicial power violating the freedom of Mrs Scott in the exercise of those elementary and constitutional rights which she possessed’.

So what, if any, statutory provisions are there affecting, in a case such as this, what was laid down in Scott v Scott? The short answer is that, apart from the Human Rights Act 1998, there are none.

I first consider the position before the Human Rights Act 1998 came into effect on 2 October 2000.

Judicial Proceedings (Regulation of Reports) Act 1926

So far as concerns the Judicial Proceedings (Regulation of Reports) Act 1926, there is a much contested and still unresolved question as to whether it applies to proceedings for ancillary relief: see Rapisarda v Colladon [2014] EWFC 1406, [2015] 1 FLR 584, [31]–[35], Cooper-Hohn v Hohn [2014] EWHC 2314 (Fam), [2015] 1 FLR 745, [30]–[70], and, most recently, Norman v Norman [2017] EWCA Civ 49, [2017] 1 WLR 2523, [2018] 1 FLR 426, [69]–[70]. And there is also a suggestion that, even if it does, it has no application to ancillary relief proceedings in chambers (see Mostyn J in Appleton and Gallagher v News Group Newspapers and PA [2015] EWHC 2689 (Fam), [2016] 2 FLR 1, [22]), a questionable proposition unsupported by the language of the Act. Be all that as it may, and even if the Act does apply to ancillary relief proceedings, including those heard in chambers, sections 1(b)(i) and 1(b)(iv) specifically exclude from the ambit of the statutory restrictions on publication ‘the names, addresses and occupations of the parties and witnesses’ and ‘the judgment of the court and observations made by the judge in giving judgment’.

Section 12 of the Administration of Justice Act 1960

Section 12 of the Administration of Justice Act 1960 does not apply to ancillary relief proceedings except, conceivably, in a very limited class of very unusual cases (I am not aware of any reported example): see Spencer v Spencer [2009] EWHC 1529 (Fam), [2009] 2 FLR 1416, [10]–[15]. And, in any event, it is elementary that even in a case where section 12 does apply, it does not prevent identification of anybody involved in the proceedings, not even the children: see Pickering v Liverpool Daily Post and Echo Newspapers plc; Pickering v Associated Newspapers Holdings plc [1991] 2 AC 370, 421, a decision of the House of Lords on the analytically identical section 12(1)(b), and Re B (A Child) (Disclosure) [2004] EWHC 411 (Fam), [2004] 2 FLR 142, [82(v)]. The reason why a child’s anonymity is protected in children proceedings is not because of section 12 of the 1960 Act; it is because of section 97 of the Children Act 1989, a provision which applies only in proceedings brought under that Act (including, it may be noted, financial proceedings under Schedule 1).

For present purposes, therefore, both the 1926 Act and the 1960 Act can be ignored.

Section 11 of the Contempt of Court Act 1981

I need also to refer to section 11 of the Contempt of Court Act 1981, which provides that:

‘In any case where a court (having power to do so) allows a name or other matter to be withheld from the public in proceedings before the court, the court may give such directions prohibiting the publication of that name or matter in connection with the proceedings as appear to the court to be necessary for the purpose for which it was so withheld.’

This seemingly applies only to proceedings held in open court (hence the reference to ‘the public’) and is therefore unlikely to be of much relevance to the hearing, almost invariably in chambers, of proceedings in the FRC. (For the use of section 11 in relation to the hearing in open court of proceedings about the medical treatment of an adult patient, see Re G (Adult Patient: Publicity) [1995] 2 FLR 528, as explained in Re HM (Vulnerable Adult: Abduction) (No 2) [2010] EWHC 1579 (Fam), [2011] 1 FLR 97.) Indeed, I am not aware of any financial remedies case where section 11 has been considered, let alone applied.

The inherent jurisdiction

Before turning to consider the impact of the 1998 Act, there are two other points to be borne in mind about the legal landscape before 2000:

- First, as was commonly understood, the undoubted power of the court to restrain the publication of the name of a child, or information about a child, was to be found in the inherent parens patriae jurisdiction in relation to children: see In re Z (A Minor) (Identification: Restrictions on Publication) [1997] Fam 1 and Kelly (A Minor) v BBC [2001] Fam 59. It was this jurisdiction which led to the creation, following the decision of Sir Stephen Brown P in the Cleveland case, Re W & Ors (Wards) (Publication of Information) [1989] 1 FLR 246, of what eventually, during the 1990s, became the familiar standard reporting restriction order: see, for the history, Harris v Harris, Attorney-General v Harris [2001] 2 FLR 895, [345]–[353].

- Secondly, it was equally the common understanding that the inherent jurisdiction in relation to adults had been abrogated in 1960 and not revived: In re F (Mental Patient: Sterilisation) [1990] 2 AC 1.

It follows that, to put it no higher, it was not all obvious that there was any jurisdiction to restrain the publication of the name of an adult or information about an adult other than under section 11 of the 1981 Act. Nor, so far as I am aware, was the attempt ever made. Indeed, it is notable that when, as in Re G (Adult Patient: Publicity) [1995] 2 FLR 528, it was desired to impose such restraint, the jurisdictional basis was indeed found in section 11.

Human Rights Act 1998

As already noted, the Human Rights Act 1998 came into effect on 2 October 2000. It was very quickly identified as providing a mechanism enabling the grant, in an appropriate case, of an order restraining the publication of the name of an adult or information about an adult: see, for example, the judgments of Dame Elizabeth Butler-Sloss P in Venables v News Group Newspapers Ltd & Ors [2001] Fam 430, in X (A Woman Formerly known as Mary Bell) v O’Brien [2003] EWHC 1101 (QB), [2003] 2 FCR 686, and in In re a Local Authority (Inquiry: Restraint on Publication) [2004] EWHC 2746 (Fam), [2004] Fam 96.

The point emerged very early on in the context of proceedings, heard in chambers, under Part IV of the Family Law Act 1996. The claim was for an occupation order in a case involving unmarried partners. The question arose as to whether the man could obtain an injunction to restrain the woman talking about the proceedings and telling her story to a newspaper. I held that, at the end of the day, this question fell to be resolved by having regard to and balancing the interests of the parties and the public as protected by Articles 6, 8 and 10 of the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms (the Convention), considered in the particular circumstances of the case: Clibbery v Allan & Anor [2001] 2 FLR 819, [120]–[154]. It is important to recognise that this approach, and indeed my decision on the point, were unanimously upheld by the Court of Appeal, which dismissed the appeal: Clibbery v Allan [2002] EWCA Civ 45, [2002] Fam 261, [82]–[83], [86], [119], [121].

In In re S (A Child) (Identification: Restrictions on Publication) [2004] UKHL 47, [2005] 1 AC 593, the House of Lords made clear ([23]) that:

‘since the Human Rights Act 1998 came into force in October 2000, the earlier case-law about the existence and scope of the inherent jurisdiction need not be considered in this case or in similar cases. The foundation of the jurisdiction to restrain publicity in a case such as the present is now derived from convention rights under the European Convention. This is the simple and direct way to approach such cases.’

Thus the previous distinction in this context between the principles applying in the case of a child and those applying in the case of an adult have been swept away. In each case the governing principles are those to be found in the 1998 Act and the Convention.

It follows from all this that that the 1998 Act and the Convention are central to the issue we are considering. They are indeed, I suggest, determinative.

Fletcher Moulton LJ’s ringing declaration of principle as to the litigant’s right to speak is now to be found in the jurisprudence of the Convention. As the Court of Appeal has recently explained (Tickle v Griffiths [2021] EWCA Civ 1882, [27]–[28]):

‘27. The right to freedom of expression, protected by Article 10 of the Convention, encompasses a right to speak to others, including the public at large, about the events and experiences of one’s private and family life. As Munby J (as he then was) pointed out in Re Angela Roddy [2003] EWHC 2927 (Fam), [2004] EMLR 8 [35–36] this is also a facet of the right to respect for private and family life:“amongst the rights protected by Article 8 … is the right, as a human being, to share with others – and, if one so chooses, with the world at large – one’s own story …”.

28. Corresponding to the right of an individual to impart information about his or her private and family life, without interference by a public authority, is the fundamental right of others to receive such information, without such interference. That is a right enjoyed by the media parties here, as well as the general public.’

Of course, as the Court of Appeal went on to explain, this is not an absolute right, for both Article 8 and Article 10 are qualified by ‘the need to protect the rights of others who are participants in the “story”’. To this extent the principle enunciated by Fletcher Moulton LJ is now modified, because section 6 of the Human Rights Act 1998 imposes on the court, as a public authority, the duty ‘[not] to act in a way which is incompatible with a Convention right’.

But – and for present purposes this is the vital point – the law requires that, before coming to the conclusion that a party to litigation is to be barred from speaking out (and, if that is what they wish, speaking out using their own name) the court must first undertake the well-known ‘balancing exercise’ mandated by the decision of the House of Lords in In re S (A Child) (Identification: Restrictions on Publication) [2004] UKHL 47, [2005] 1 AC 593: see, for a well-known example, Re P (Enforced Caesarean: Reporting Restrictions) [2013] EWHC 4048 (Fam), [2014] 2 FLR 410.

Moreover, as the Court of Appeal went on to observe in Tickle v Griffiths, [30], referring to O (A Child) v Rhodes [2014] EWHC 2468 (QB), [2014] EWCA Civ 1277, [2015] EMLR 4, [2015] UKSC 32, [2016] AC 219, ‘the right to tell one’s own story is likely to carry considerable weight’. Indeed, the one aspect of the judgment of Lieven J at first instance which the Court of Appeal criticised was when it observed ([70]) that ‘Lieven J may, if anything, have slightly undervalued this aspect of the case’.

There is, moreover, clear authority as to how the balancing exercise is to be applied where what is sought is the anonymisation of the litigants. Mostyn J has set out for us in full (Xanthopoulos v Rakshina, [104]) what Lord Neuberger MR said in H v News Group Newspapers Ltd [2011] EWCA Civ 42, [2011] 1 WLR 1645, [21], so I confine myself to the key parts of Lord Neuberger’s summary:

‘(1) The general rule is that the names of the parties to an action are included in orders and judgments of the court.

(2) There is no general exception for cases where private matters are in issue.

(3) An order for anonymity or any other order restraining the publication of the normally reportable details of a case is a derogation from the principle of open justice and an interference with the Article 10 rights of the public at large.

(4) Accordingly, where the court is asked to make any such order, it should only do so after closely scrutinising the application, and considering whether a degree of restraint on publication is necessary, and, if it is, whether there is any less restrictive or more acceptable alternative than that which is sought.

(5) Where the court is asked to restrain the publication of the names of the parties and/or the subject matter of the claim, on the ground that such restraint is necessary under Article 8, the question is whether there is sufficient general, public interest in publishing a report of the proceedings which identifies a party and/or the normally reportable details to justify any resulting curtailment of his right and his family’s right to respect for their private and family life.

(6) On any such application, no special treatment should be accorded to public figures or celebrities: in principle, they are entitled to the same protection as others, no more and no less.

(7) An order for anonymity or for reporting restrictions should not be made simply because the parties consent: parties cannot waive the rights of the public.’

In this connection one needs also to consider Lord Neuberger’s subsequent Practice Guidance (Interim Non-disclosure Orders) [2012] 1 WLR 1003. I quote the key parts:

‘4. Applications which seek to restrain publication of information engage article 10 of the Convention and section 12 of the Human Rights Act 1998 (“HRA”). In some, but not all, cases they will also engage article 8 of the Convention. Articles 8 and 10 of the Convention have equal status and, when both have to be considered, neither has automatic precedence over the other. The court’s approach is set out in In re S (A Child) (Identification: Restrictions on Publication) [2005] 1 AC 593, para 17. ...

9. Open justice is a fundamental principle. The general rule is that hearings are carried out in, and judgments and orders are, public …

10. Derogations from the general principle can only be justified in exceptional circumstances, when they are strictly necessary as measures to secure the proper administration of justice. They are wholly exceptional … Derogations should, where justified, be no more than strictly necessary to achieve their purpose.

11. The grant of derogations is not a question of discretion. It is a matter of obligation and the court is under a duty to either grant the derogation or refuse it when it has applied the relevant test …

12. There is no general exception to open justice where privacy or confidentiality is in issue. Applications will only be heard in private if and to the extent that the court is satisfied that by nothing short of the exclusion of the public can justice be done. Exclusions must be no more than the minimum strictly necessary to ensure justice is done and parties are expected to consider before applying for such an exclusion whether something short of exclusion can meet their concerns, as will normally be the case … Anonymity will only be granted where it is strictly necessary, and then only to that extent.

13. The burden of establishing any derogation from the general principle lies on the person seeking it. It must be established by clear and cogent evidence ...

14. When considering the imposition of any derogation from open justice, the court will have regard to the respective and sometimes competing Convention rights of the parties as well as the general public interest in open justice and in the public reporting of court proceedings … On the other hand, the principle of open justice requires that any restrictions are the least that can be imposed consistent with the protection to which the party relying on their article 8 Convention right is entitled.’

Ah, but I hear you murmuring, what is that to do with us? That was a civil case, not a family case, and things are different in the Family Court and the FRC. Why? This is simply another revival of the desert island heresy. And, in fact, the Court of Appeal has now three times applied Lord Neuberger’s approach in financial remedy cases: K v L [2011] EWCA Civ 550, [2012] 1 WLR 306, Norman v Norman [2017] EWCA Civ 49, [2017] 1 WLR 2523, [2018] 1 FLR 426, and XW v XH [2019] EWCA Civ 549, [2019] 1 WLR 3757.

The emergence of the present practice in financial remedy cases

So what is the basis for the contention that judgments in financial remedy cases should be anonymised? And when did the present practice of almost routine anonymisation emerge?

Ancillary relief as we know it today, as provided for by Part II of the Matrimonial Causes Act 1973, did not exist prior to the enactment of the Matrimonial Proceedings and Property Act 1970. Before then, the court had wide powers to make orders in relation to income, variously described in different contexts – the details do not matter for present purposes – as alimony, maintenance and periodical payments. In relation to capital, in contrast, the court’s powers were very limited. Under section 45 of the Matrimonial Causes Act 1857 and its successor provisions the court could direct the settlement of an adulterous wife’s property (the scope of this was later extended to other forms of a wife’s misconduct: see now section 24(1)(b) of the 1973 Act). Under section 5 of the Matrimonial Causes Act 1859 (see now section 24(1)(c) of the 1973 Act) the court could vary any ante-nuptial or post-nuptial settlement. That was all.

Mostyn J has summarised for us the development of the practice in relation to this: Xanthopoulos v Rakshina, [78]–[88]. There is no need for me to add anything to what he has said. I take it as read.

The important point for present purposes is to note how very infrequent was the anonymisation of financial remedies cases in that era. A useful snapshot is provided by Tolstoy on Divorce.[[7]] The chapter on financial provision (alimony, maintenance and periodical payments, and variation of settlements) runs to 44 pages. Of the scores of cases cited, only five are anonymised: K v K (Otherwise R) [1910] P 140, M v M [1928] P 123, CL v CFW [1928] P 223, N v N (1928) 138 LT 693 and J-PC v J-AF [1955] P 215. None of them, it may be noted, was a settlement case. Indeed, as Mostyn J has pointed out (A v M, [105]), the first anonymisation of such a case was as late as 2005 when N v N and F Trust [2005] EWHC 2908 (Fam), [2006] 1 FLR 856 was reported in that form.

Thirty years later the picture had begun to change, quite markedly, as illustrated by the following table: it shows the number of first instance ancillary relief cases reported in the Family Law Reports (FLR) since the first volume in 1980 and how many of those cases are anonymised.

| Total | Anonymised | % of total | |

| 1980–2021 | 554 | 364 | 65.7 |

| Broken down | |||

| 1980–89 | 84 | 18 | 21.4 |

| 1990–99 | 70 | 51 | 72.9 |

| 2000–09 | 149 | 114 | 76.5 |

| 2010–19 | 219 | 158 | 72.1 |

| 2020–21 | 32 | 23 | 71.9 |

| 1990–2021 | 470 | 346 | 73.6 |

It can be seen that from 1990 onwards the overall anonymisation rate has been 73.6%.

This rate is supported by analysis of all the first instance ancillary relief cases listed in At A Glance, 2021–2022. This shows that of the 374 cases listed (covering the period since 1970 though with comparatively few cases from the 1970s and 1980s), 270 – 72.2% – are anonymised.

Plainly, something dramatic occurred in the 1990s.

Mostyn J has pointed to the significance of the introduction of the judgment template incorporating the standard rubric: Xanthopoulos v Rakshina, [117]–[121]. I would respectfully agree with him that this has had, and continues to have, a very significant causative effect on the practice of anonymisation in financial remedies cases. However, the picture is, I suggest, somewhat more complex than he has suggested – though I emphasise at once that this has no effect at all on the correctness of his ultimate conclusion.

At about the turn of the Millennium, five innovations created the practice with which we are now familiar:

(1) In 1999, BAILII started publishing the judgments of the judges of the Family Division in their original form (earlier judgments on BAILII seem to have been derived from what had been published in law reports): in the case of written judgments, the judgment as prepared by the judge; in the case of extempore judgments, the official transcript as approved by the judge.

(2) With effect from 11 January 2001, all judgments in the Family Division (as in the other Divisions of the High Court and Court of Appeal) were required to have single spacing and paragraph numbering: Practice Direction (Judgments: Form and Citation) [2001] 1 WLR 194, [1.1].

(3) During 2001[[8]] the practice emerged of attaching two standard form rubrics to written judgments handed down in the Family Division. In their developed form, one rubric read as follows:

‘I direct that pursuant to CPR PD 39A para 6.1 no official shorthand note shall be taken of this Judgment and that copies of this version as handed down may be treated as authentic.’[[9]]

The only significance of this for present purposes was that the official shorthand-writers were no longer concerned with the transcribing of written judgments, only with the transcribing of judgments delivered ex tempore. The other rubric (what I shall refer to hereafter as ‘the rubric’), in its developed form, read:

‘This judgment was handed down in private on [date]. The judge hereby gives leave for it to be reported. The judgment is being distributed on the strict understanding that in any report no person other than the advocates or the solicitors instructing them (and other persons identified by name in the judgment itself) may be identified by name or location and that in particular the anonymity of the children and the adult members of their family must be strictly preserved.’[[10]]

(4) With effect from 14 January 2002, the use of neutral citation numbers (previously confined to the Court of Appeal and the Administrative Court) was extended to the Family Division (as to the other Divisions of the High Court): Practice Direction (Judgments: Neutral Citations) [2002] 1 WLR 346, [1].

(5) During 2002, electronic templates for the preparation of written judgments were made available to the judges. These templates: (a) automatically formatted the judgment so as to comply with Practice Direction (Judgments: Form and Citation) [2001] 1 WLR 194, [1.1]; (b) automatically generated the appropriate form of neutral citation number; and, in the case of the Family Division template, (c) automatically inserted both rubrics (though the judge could, if desired, alter the text of the rubrics or delete them altogether).

It will be appreciated that none of these developments can explain the increase of anonymised judgments from 21.4% in the 1980s to 72.9% in the 1990s.

It is important to recognise one crucially important factor which makes the anonymity of reported judgments an uncertain proxy for judicial behaviour. With only a handful of exceptions (I have in mind the Tax Cases – TC – ‘Published under the direction of the Board of the Inland Revenue’, and the Immigration Appeal Reports – Imm AR – published by The Stationery Office for the Upper Tribunal (Immigration and Asylum Chamber)), none of which is relevant for present purposes, law reports are not, and never have been, official publications sanctioned or controlled by the judges or, indeed, by any public authority. They are, as they always have been, produced by private commercial publishers (this is so even in the case of the so-called ‘Official Reports’ published by the Incorporated Council of Law Reporting, except that it operates as a charity). As Lord Woolf CJ said in Practice Direction (Judgments: Neutral Citations) [2002] 1 WLR 346, [6], ‘the judges cannot dictate the form in which law publishers reproduce the judgments of the court’.

It follows from this that, although, if a judgment is reported with the names of the parties, we can be confident that the judge has not stipulated anonymity, the converse is by no means necessarily true. A case may have been anonymised by the judge; it may, on the other hand, have been anonymised by the law reporter.

In his judgment in Scott v Scott [1912] P 241, 281–282, Fletcher Moulton LJ referred to the change in practice in the 1850s and 1860s when the names of parties in nullity cases, which had previously been set out in full, were now replaced with initials. He attributed this change of practice to the ‘private undertakings’ responsible for the publication of law reports.

Prior to 1999 we have no means of knowing what was going on ‘behind the scenes’ in the case of first instance judgments: as we shall see, BAILII was to change all that. However, some information was, and is, available in relation to appellate judgments. Beginning in, I believe, 1951 an official collection, housed in the Royal Courts of Justice, was made of the official transcripts of judgments in the Court of Appeal (including many cases that were never published in any law report); and for many years the judgments of the House of Lords as handed down had been in the public domain. These sources are interesting for what they reveal.

I referred above to the five anonymised cases cited in Tolstoy on Divorce.[[11]] The first four are all judgments at first instance. All we can tell from the published reports is that K v K (Otherwise R) [1910] P 140 (a decision of Bargrave Deane J) arose in the context of a nullity case where the respondent wife was of unsound mind; and that CL v CFW [1928] P 223 (Lord Merrivale P) was a divorce case in which the respondent husband was of unsound mind. In neither case, therefore, was the anonymisation of the parties in any way unusual in terms of contemporary practice. In contrast, M v M [1928] P 123 (Lord Merrivale P) was a judicial separation case and N v N (1928) 138 LT 93 (Lord Merrivale P) a divorce case in which neither party was of unsound mind. Why they should have been anonymised is unclear.

In the fifth case, J-PC v J-AF [1955] P 215, also published as J v J [1955] 2 All ER 617, there is nothing to tell us why the judgment at first instance of Sachs J was published in anonymised form. It was a divorce case where neither party was of unsound mind. The original transcript of the judgments of the Court of Appeal as prepared by the Official Shorthand Writers, at that time the Association of Official Shorthandwriters Limited, is, however, available and is now accessible on JustisOne. It shows that the case was in fact Jones v Jones and Goddard – though I note that Sachs J had referred to the woman named as Mrs W. So, the decision to anonymise was, seemingly, that of the law reporters, not the Court of Appeal.

We can see from BAILII, which reproduces the judgment of the House of Lords as handed down in the case reported as In re F (Mental Patient: Sterilisation) [1990] 2 AC 1, that the House of Lords anonymised the handed down judgment and entitled it ‘In re F (Respondent)’. There was, however, no prohibition on the naming of F; indeed, the order made by the House of Lords on the appeal, which is in the public domain and is published by BAILII, sets out F’s name in full, as well as the name of her mother, her next friend. So the decision to anonymise was that of the judges, but was not accompanied by any prohibition on the naming of the parties.

Unfortunately, so far as concerns first instance judgments, we are never likely to be able to get to the bottom of what was going on in the 1980s and 1990s before the arrival of BAILII. We cannot tell whether the anonymisation of any particular case was determined by the judge or by the law reporter. We can, however, be pretty confident that even if a judgment had been anonymised by the judge this will not have been accompanied by any direction for secrecy by the judge, whether by rubric (for the rubric had not yet been invented) or by reporting restriction order (for at that time such orders were confined to cases involving children) or otherwise. Put another way, anonymisation involved no more than a decision not to supply the names of the parties; it was not a prohibition on the naming of the parties.

With the advent of BAILII it is now possible to see in much more detail exactly what is going on. As I have said, what BAILII publishes is, in the case of a written judgment, the judgment as prepared by the judge; in the case of an extempore judgment, the official transcript as approved by the judge. Moreover, where a rubric has been attached to a judgment by the judge, BAILII publishes the rubric. Thus, anyone who studies a judgment as published on BAILII can readily see:

- Whether the judgment was extempore (in which case the name of the official shorthand-writer is given) or handed down in writing.

- Whether, where this was shown by the judge, a written judgment was handed down in private or in open court.

- Whether in the case of an anonymised judgment there is a rubric.

It follows that in the case of an anonymised written judgment the decision to anonymise will have been that of the judge. It should be noted that where what is published on BAILII is an anonymised official transcript, one cannot tell whether the anonymisation originated with the shorthand writer who prepared the transcript (as I suspect will have happened in many cases) or with the judge who approved it.

Examination of anonymised financial remedies cases published on BAILII reveals that there are many such cases (including many judgments of mine at first instance) where, although the judge has determined that there should be anonymisation, there is nonetheless no rubric. In other words, although the judge has decided not to supply the names of the parties, there is no judicial prohibition on the naming of the parties. The inevitable corollary of this is that one cannot assume, just because a judgment has been anonymised (even judicially anonymised), that there is any judicial prohibition on the naming of the parties.

In contrast, law reports still typically publish judgments in such a way as not to make clear whether the judgment was written or extempore and often, moreover, without including the rubric.[[12]] The consequence, as will be appreciated, is that the reader of an anonymised judgment in a law report will not be able to tell whether the anonymisation originated with a shorthand writer, with the judge or with the law reporter. Of much more importance, unless the judge has referred to it in the body of judgment itself, the reader of an anonymised judgment in a law report may not be able to tell whether there is a rubric.

The position, it might be thought, is most unsatisfactory.

The rubric

Let it be assumed, however, that an anonymised judgment has been published with a rubric. Where does this take us? If Mostyn J is right – and he is – the answer is simple: nowhere. Let me elaborate.

It is important to remember that, unless embodied in an order of the court, a judicial expression of view, a judicial warning, or a judicial statement of what can or cannot be published is a waste of breath and not worth the paper on which, if written, it is recorded: see R v Socialist Worker Printers and Publishers Ltd ex parte Attorney-General [1975] QB 637, 646 (Lord Widgery CJ), Attorney-General v Leveller Magazine Ltd [1979] AC 440, 473 (Lord Scarman).

In the context of ancillary relief, consider Spencer v Spencer [2009] EWHC 1529 (Fam), [2009] 2 FLR 1416, [19]–[22]. I had been invited by counsel ‘to make abundantly clear to the media’ that the 1926 Act applied to the proceedings before me. I refused to do so, observing ([21]) that:

‘what I am being invited to do is to give an advisory opinion and to offer advice to the media – advice which it is insinuated will carry the more force because it comes from a judge. The difficulty is that although persons, the media included, may be obliged to obey the orders of a judge, if the judge offers advice they are entitled to accept or reject that advice as they wish, just as they are entitled to accept or reject advice from any other quarter. So, were I to express any views on the matter, and all the more so were I to address the media in the way suggested, not merely would I be stepping outside any proper judicial function, I would not, in fact, be achieving anything of utility to the parties.’

This was followed by Roberts J in Cooper-Hohn v Hohn [2014] EWHC 2314 (Fam), [2015] 1 FLR 745, [28].

Moreover, if it is to be effective and enforceable, if the need arises, as an order, it must be drafted in the way in which injunctions are usually drafted and, moreover, in terms which are clear, precise and unambiguous; there must be a penal notice; and the procedures required by section 12(3) of the Human Rights Act 1998 and Practice Direction 12I: Applications for Reporting Restriction Orders must be complied with: see Re HM (Vulnerable Adult: Abduction) (No 2) [2010] EWHC 1579 (Fam), [2011] 1 FLR 97, and Re RB (Adult) (No 4) [2011] EWHC 3017 (Fam), [2012] 1 FLR 466.

The purpose and effect of the rubric are, I suspect, still not as well understood as one would like.

For many years, so far as I am aware, the meaning and effect of the rubric attracted neither curiosity nor judicial consideration. I think I am correct in saying that the point first arose, as it happened before me, in Re B, X Council v B [2007] EWHC 1622 (Fam), [2008] 1 FLR 482, and then again Re B, X Council v B (No 2) [2008] EWHC 270 (Fam), [2008] 1 FLR 1460, when I was asked to make successive modifications to the rubric (the first to allow naming of the local authority, the second to allow naming of certain family members) which I had attached to an earlier judgment reported as X Council v B (Emergency Protection Orders) [2004] EWHC 2015 (Fam), [2005] 1 FLR 341. On each occasion as I made clear, I merely assumed, though without deciding the point, that ‘the rubric is binding on anyone who seeks to make use of a judgment to which it is attached’ – though I did not seek to explain how or why: Re B, X Council v B (No 2) [2008] EWHC 270 (Fam), [2008] 1 FLR 1460, [12].

Three years later, in 2011, I engaged with the question and sought to provide an answer.

The starting point, as I explained in Re RB (Adult) (No 4) [2011] EWHC 3017 (Fam), [2012] 1 FLR 466, [13], is that:

‘The rubric is not an injunction: see Re HM (Vulnerable Adult: Abduction) (No 2) [2010] EWHC 1579 (Fam), [2011] 1 FLR 97. It is not drafted in the way in which injunctions are usually drafted. There is no penal notice. And the procedures required by section 12(3) of the Human Rights Act 1998 and Practice Direction 12I: Applications for Reporting Restriction Orders will not have been complied with.’

But, I went on, ‘this does not mean that it is unenforceable and of no effect’. I went on to explain why ([15]–[16]):

‘15. … the publication of a judgment in a case in the Family Division involving children, is subject to the restrictions in section 12(1)(a) of the Administration of Justice Act 1960. To publish or report such a judgment without judicial approval is therefore a contempt of court irrespective of whether or not it is in a form which also breaches section 97(2) of the Children Act 1989.

16. The rubric is in two parts and serves two distinct functions. The first part (“The judge hereby gives leave for it to be reported”) has the effect, as it were, of disapplying section 12 pro tanto, and thereby immunising the publisher or reporter from proceedings for contempt. But the second part (“The judgment is being distributed on the strict understanding that …”) makes that permission conditional. A person publishing or reporting the judgment cannot take advantage of the judicial permission contained in the first part of the rubric, and will not be immunised from the penal consequences of section 12, unless he has complied with the requirements of the second part of the rubric. This is merely an application of a familiar principle which one comes across in many legal contexts and which finds expression in such aphorisms as that you cannot take the benefit without accepting the burden, that you cannot approbate and reprobate and that if a thing comes with conditions attached you take it subject to those conditions.’

Re RB was a case involving an incapacitated adult where I was exercising the inherent jurisdiction. Section 12, therefore, had no application (see [9]). I had handed down various judgments in private (in chambers), each including in the heading the words ‘In Private’. I had deliberately omitted the rubric. I explained why ([20]):

‘Since section 12 did not apply, there was no need for me to include the first part of the rubric; and absent the first part there was neither need nor justification for the second part.’

I have to confess that this had not always been my understanding. BAILII shows that in two cases, one reported as Re S (Adult Patient: Inherent Jurisdiction: Family Life) [2002] EWHC 2278 (Fam), [2003] 1 FLR 292, and the other as HE v A Hospital NHS Trust [2003] EWHC 1017 (Fam), [2003] 2 FLR 408, each relating to the social or medical care of an incapacitated adult, my judgment as handed down in private was not merely anonymised but also included the full rubric. That, of course, as I must accept, was an error on my part.

It is convenient to mention also Re X (A Child) (No 2) [2016] EWHC 1668 (Fam), [2017] 2 FLR 70, where I had handed down a judgment in open court. It was suggested that, in error, the rubric had been omitted. I rejected the argument. Having referred to the analysis in Re RB, I said ([5]):

‘Now none of this has any application to a judgment handed down in public. The rubric in its standard form applies, as a matter of language, only to judgments handed down in private. But there is a more fundamental point in play here. Section 12 (which applies only to reports of “proceedings before [a] court sitting in private”) does not apply to the contents of a judgment handed down in public. Nor, as a quite separate point, does anyone need a judge’s permission to publish or report a judgment given or handed down in public, unless, that is, there is in place, and there was not here, some specific injunctive or other order preventing publication. It will thus be seen that there was no basis for my including the rubric in my judgment.’

On 13 April 2022, the day after Mostyn J had handed down his judgment in Xanthopoulos v Rakshina, Moor J handed down, in public, a judgment in a financial remedies case (it was, in fact, an appeal) in which the parties were named: Lockwood v Greenbaum [2022] EWHC 845 (Fam). The attached rubric read:

‘This judgment was delivered in public. It can be reported in full but the two children of the parties must not be identified other than as they are referred to in the judgment. All persons, including representatives of the media, must ensure that this condition is strictly complied with. Failure to do so will be a contempt of court.’

With all respect to the judge, this surely invites two questions, to neither of which there is a satisfactory answer: (1) What (if any) is the effect of this in law? (2) What is the basis for the assertion that failure to comply ‘will be a contempt of court’?[[13]]

It is fairly clear that Moor J’s approach is not consistent with that of Mostyn J.

It can thus be seen that the rubric has no proper role to play in a financial remedy case where, to repeat, there is, in contrast to a case involving a child, no statutory prohibition on the publication of a judgment handed down in chambers, and, absent any reporting restriction order, nothing to prevent anyone doing so. Absent any statutory prohibition, the first part of the rubric is unnecessary and, if nonetheless included, wholly redundant. For the would-be publisher does not need the permission of the court to publish and can justify publication, and defend a complaint of contempt, without reference to the first part of the rubric. That being so, there is nothing for the second part of the rubric to bite on. Since the would-be publisher does not need the permission of the court gratuitously granted by the first part of the rubric in order to defend a complaint of contempt, he can publish without having to comply with the requirements of the second part of the rubric.

I therefore agree entirely with Mostyn J’s conclusion (Xanthopoulos v Rakshina, [119]) that ‘in a financial remedy case heard in private … the standard rubric is completely ineffective to prevent full reporting of the proceedings or of the judgment’.

There is a further point to be noted. Use in this context of the current form of rubric raises the question whether it is appropriate, indeed lawful, to seek to threaten a penalty for contempt in a case where there is in fact no reporting restriction order.

Clibbery v Allan

As we have seen, Mostyn J has cast a critical eye over certain dicta in Clibbery v Allan [2002] EWCA Civ 45, [2002] Fam 261, especially the statement by Thorpe LJ ([106]) that:

‘I have no difficulty in concluding that in the important area of ancillary relief, … all the evidence (whether written, oral or disclosed documents) and all the pronouncements of the court are prohibited from reporting and from ulterior use unless derived from any part of the proceedings conducted in open court or otherwise released by the judge.’

The reasoning leading to this conclusion appears from what Thorpe LJ had previously said ([93], [100]):

‘93. In the family justice system the designation “in chambers” has always been accepted to mean strictly private. Judges, practitioners and court staff are vigilant to ensure that no one crosses the threshold of the court who has not got a direct involvement in the business of the day … This strict boundary has always been scrupulously observed by the press. Of course the judge always retains a residual discretion and, accordingly, a hearing in chambers may culminate in a judgment in open court. Alternatively the judge may make an abbreviated statement in order that the public interest in the proceedings may be at least partially satisfied.

100. … family proceedings are easily distinguishable from civil proceedings in the other Divisions of the High Court … in family proceedings the relationship between the court and the litigants is clearly distinguishable from the relationship between the litigants and the court in civil proceedings. In the latter the parties bring into the arena such material as they choose to bring together with such material as they may be ordered to bring during the development of the case … The determination of an ancillary relief application proceeds on a very different basis … All parties are under a duty of full and frank disclosure, clearly recognised well before the advent of the statutory powers for equitable redistribution of assets on divorce.’

He went on ([104]–[105]) to refer to the well-known speech of Lord Brandon of Oakbrook in Livesey v Jenkins [1985] AC 424 and to the implied undertaking not to disseminate litigation material ‘for ulterior purposes’.

Thorpe LJ was, of course, entirely correct to emphasise just how extensive are the obligations under Livesey v Jenkins [1985] AC 424 and under the implied undertaking. But one is nonetheless entitled to question how he managed to get from there to his sweeping conclusion.

I do not propose to traverse again the ground which Mostyn J has already covered. And in venturing a view I am very conscious that I am parti pris, for I had been the judge at first instance whose judgment (Clibbery v Allan & Anor [2001] 2 FLR 819) was being dissected by the Court of Appeal. Nonetheless, I trust that a few observations are in order:

(1) It is not immediately apparent how Thorpe LJ’s conclusion is to be reconciled with the proposition, accepted, as we have seen, by the Court of Appeal in the very same case, that a proposed prohibition of publication was to be resolved having regard to and balancing the interests of the parties and the public as protected by Articles 6, 8 and 10 of the Convention, considered in the particular circumstances of the case.