A Beginner's Guide to Deferred Compensation (and Other Forms of Remuneration)

Introduction

For most people earned income means periodic salary payments, received net of tax, from an employer. However, for a comparatively small cohort of people, earned ‘income’ can look a lot more complicated and uncertain. It might take on a different form to that of a simple cash payment. It might be received some time after the period in which it is earned. It may be wholly or partly dependent on some future event or performance.

Financial remedy practitioners must be ready to deal with parties who benefit from more complex pay structures. That can be a daunting task. In our experience, these remunerative structures can be intimidating and inscrutable to outsiders, despite being common and comprehensible to people in certain sectors of industry. Indeed, they are often defined with jargon and acronyms (RSUs, LTIPs, RSOs, PSOs etc.) that might sound like gibberish to the uninitiated.

These remunerative structures have multiple attractions for employers and are increasingly common. They help to align the motivations and fortunes of the employer and employee. By linking the value of the employee’s pay packet to the fortunes of the employer company, they can incentivise performance. Deferring payment of future remuneration and making it subject to continued employment (or more specific performance conditions) gives employees a motive to stay put and keep up their hard work, which will hopefully assist the long-term performance of the business.

It is for this reason that the term ‘Long Term Incentive Plan’ (‘LTIP’) is sometimes used to refer to deferred compensation arrangements comprised of periodically granted parcels of equity instruments in the employer company (e.g. shares or options). Typically, these LTIPs have a built-in delay in receipt, contingent on continuing employment and sometimes linked to specific individual and/or company performance conditions.

In this article, we explore these deferred compensation structures, as well as other related forms of remuneration, and how they might be approached by financial remedy practitioners. We attempt to:

(1) Introduce and define the term ‘deferred compensation’;

(2) Define, in broad terms, common forms of deferred compensation and consider how they can be ascribed value. We also raise specific considerations for each form of deferred compensation in the context of financial remedy proceedings; and

(3) Outline the court’s general approach to deferred compensation in financial remedy cases and discuss some remaining areas of uncertainty.

What do we mean by deferred compensation?

For ease of reference, we use the generalised term ‘deferred compensation’ to refer to pay structures with an element of delay or uncertainty to their receipt.[[1]] In this article, we consider:

(1) Restricted Stock Units (‘RSUs’);

(2) Options;

(3) Carried Interest (or ‘Carry’);[[2]] and

(4) Co-Investment.

Throughout this article we refer to the payers of compensation as ‘employers’, and the recipients as ‘employees’. We appreciate that this is an oversimplification, and that the formal taxonomy of remunerative relationships between payer and recipient can be more complex.

Before we are branded as heretics, a word about Carry and Co-Investment. We know that many would argue that Carry and Co-Investment are not properly classified as deferred compensation. That said, both have features in common with more conventional forms of deferred compensation, and both are often inextricably linked to the terms of an ‘employee’s’ engagement. They are thus included in the scope of this article: we will get to their distinguishing features in due course.

Finally, this article self-identifies as a ‘beginner’s guide’. It is intended to be a high-level introduction. It includes a few medium-depth detail dives, but there is a limit to how specific or prescriptive an article of this nature can be. Whilst we attempt to identify common threads, deferred compensation schemes are often bespoke to individual employers and/or employees. As such, it is ultimately the employer and employee who are best placed to resolve any ambiguities about their operation. More on this later.

(1) Restricted Stock Units (RSUs)

What are they?

RSUs are units of stock (shares) in the ‘employer’ company that are awarded on a given date (the ‘grant date’) and vest, sometimes periodically, over a pre-determined time period.

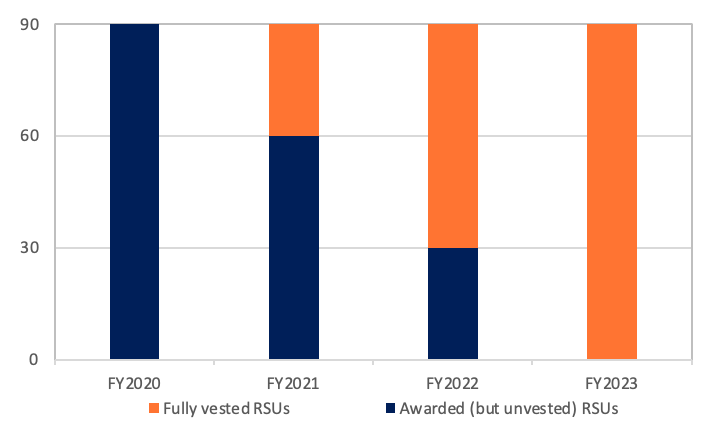

RSUs are often granted as part of a wider package of total compensation in a given earning year. RSUs are ‘restricted’ during the vesting period which is dictated by specific terms that attach to the RSUs. Typically this is a set time period. Three years is a common vesting period, but it can be longer or shorter than this and the vesting periods may differ for different tranches of RSUs. This is illustrated in the figure below.

Generally, the recipient employee cannot realise or deal with the shares during the vesting period. At the vest date, the shares become realisable and are effectively released to the recipient. Often, tax is payable at the point of vesting, and a portion of the shares are sometimes withheld by the employer to meet any tax falling due. The recipient employee will then receive the net balance of the shares, which they can sell at the prevailing share price to realise cash.

From an administrative perspective, RSUs (vested and unvested) are sometimes held in a nominee third party portfolio account, set up to receive the RSUs from the employer. Generally, RSUs do not pay dividends prior to their vesting, although occasionally employers might grant the equivalent of dividends to accrue in an escrow account.

How are they valued?

For RSUs granted in a publicly traded company, the current listed share price provides a helpful and indicative starting point as to their value. For RSUs in privately held companies, things are more complex. To form a reliable view as to the value of the RSUs, it is first necessary to have an understanding of the value of the company as a whole, having specific consideration to its differing classes of shares, including the RSUs, which may in turn require expert business valuation evidence.

However, as a practical point, it is common for businesses to perform valuations, whether these are undertaken by management or third-party advisors, when implementing share schemes and RSU grants. Requesting such valuations or other relevant information can be a helpful step when assessing the value of RSUs in privately held businesses.

Regardless of whether the RSUs are in publicly listed or privately held companies, from a pure valuation standpoint, the specific terms of their restrictions will also dictate the extent to which valuation discounts should apply to reflect a lack of marketability. In both cases, there are relevant studies that are informative when approaching this issue. That said, the approach of the Family Court in applying discounts to RSUs for illiquidity, contingency and/or future endeavour is inconsistent, and will very much depend on the particular facts of a given case. Discounting may not arise at all if RSUs are to be subject to Wells sharing. Their net value can then be estimated by deducting any notional tax at the applicable rate. The specific tax treatment of RSUs is outside the scope of this article.

Specific considerations…

Often there is argument about the extent to which RSUs constitute shareable matrimonial property. If granted during the marriage, they will generally be viewed as matrimonial property even if subject to deferred receipt over a vesting period. The fact of deferral makes Wells sharing of RSUs an attractive option.

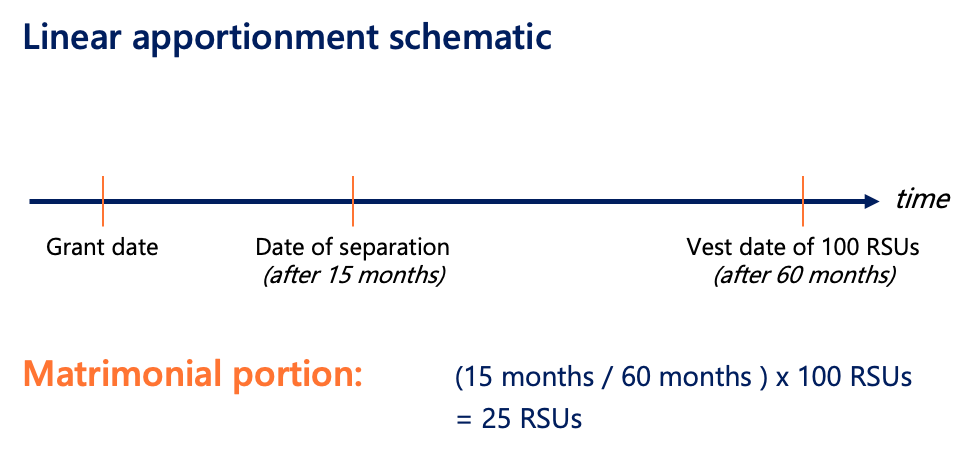

If they are not being Wells shared, practitioners should be wary of simplistic current valuations, which may chime with an atypically high or low stock price. If their vesting is subject to continuing specific performance conditions,[[3]] then there may be justification for discounting or departure from equal sharing even if granted during the marriage. In these circumstances a notional straight-line apportionment of the RSU value over the grant-vest period may be a sound method for identifying the ‘matrimonial’ element – more on this shortly. There is a distinction between performance-related vesting conditions and the more basic condition of continuing employment. The latter is less likely to justify a departure from equal sharing.[[4]]

There may also be debate about how the scheme operates in practice. The actual nature of performance conditions is often a hot topic. In the first instance, disclosure of the scheme rules may provide clarity, failing which a letter from the applicable department of the employer company may be appropriate.

(2) Options

What are they?

Call options are a form of financial derivative that gives the holder of the option the right, but not obligation, to purchase a given quantity of stock (the ‘Underlying’), at a given point in time (the ‘Exercise Date’ or ‘Expiry Date’), at an agreed price (the ‘Strike Price’ or ‘Exercise Price’).[[5]]

Unlike RSUs, options are not a grant of stock ownership to an employee and if the option is not ‘exercised’ prior to its Expiry Date, then it will lapse and will have nil value. By way of example, if the share price of the ‘Underlying’ is lower than the Strike Price (sometimes referred to as being ‘Out of the Money’) at the point of exercise, then the holder of the option will not exercise the option and let it ‘lapse’ instead. In contrast, if the share price exceeds the Strike Price, then the holder will exercise the Option and crystalise a windfall, equal to the share price less the Strike Price, multiplied by the number of options held.

As with RSUs, options can also be awarded with differing maturity dates, becoming exercisable over a given period of time, as dictated by the rules of the scheme. By way of example, an employee may be granted 90 options, with 30 becoming exercisable after year one, a further 30 after year two, and the final 30 in year three, as illustrated in the figure above.

The vesting of options may also be linked to specific performance conditions or simply continued employment. Often the exercising of the option amounts to a simultaneous purchase and sale of the stock, with the profit paid out to the employee subject to tax. Like RSUs, options are also sometimes ‘held’ in a nominee third party investment portfolio account.

How are they valued?

The valuation of options is complex and is often informed by esoteric financial models, the most popular of which is the Black-Scholes-Merton Option pricing model, for which Merton and Scholes received the 1997 Nobel Prize for Economics.[[6]] Importantly, from the perspective of finance theory, options can never have nil value. That is, even if the option is currently ‘out of the money’, it will still have a positive value to reflect the possibility that the option, may, come back into the money at expiration. Of course, the probability of such a likelihood will reflect both the current share price and time to expiry, and may be vanishingly small.

For the Black-Scholes-Merton pricing formula itself, whilst complex, its inputs are relatively straightforward comprising only five variables: (i) time to maturity; (ii) the risk-free interest rate; (iii) the volatility of the Underlying; (iv) the current price of the Underlying; and (v) the Strike Price. It follows, therefore, that if reliable estimates can be made of the requisite parameters, an estimate can be made as to the value of the options. However, it may be necessary to seek input from a reliable forensic accountant with experience of performing such calculations.

One additional consideration when estimating the value of Options held by a given individual is the specific criteria that attach to the options. By way of example, options are often granted to incentivise and reward employees for growth in the employer firm. To put this in context, if the current share price of Company A is £1, then the ‘Strike Price’ of the granted options might be, say, £1.20, to incentivise the employee to contribute to growing the value of the firm by 20%. However, without knowing the current value of the business, the agreed ‘Strike Price’, set at some historical point in time, tells you relatively little as to the actual, current value of the business. As such, information provided alongside any grant of options should be scrutinised with care.

Specific considerations…

The same considerations apply to options as to RSUs. First, consideration will need to be given to the grant date, vesting date, any attached continuing specific performance conditions, and the reliability of their ascribed present value if they are not being Wells shared.

In our experience, the more rigorous valuation approaches outlined above are routinely overlooked. Practitioners and judges often take the more simplistic approach of ascribing the gross value as the share price at trial less the strike price, multiplied by the number of options, before perhaps applying an (often arbitrary) discount. We were famously reminded by Moylan J (as he then was) in H v H [2008] EWHC 935 (Fam) that the computation phase in financial remedy cases is not supposed to be a ‘detailed accounting exercise’ to achieve ‘mathematical/accounting accuracy which is invariably no more than a chimera’. The degree of valuation rigour required will be a case-specific question and will need to be balanced against the potential value of the options in question. That said, we warn that the ‘simplistic’ approach above may sometimes be inappropriate, especially in cases with proportionately large quantities of options that are not to be Wells shared in specie.

(3) Carried Interest

What is it?

The right to participate in, and receive, Carried Interest or ‘Carry’ is typically awarded to senior individuals, often partners and fund managers, in Private Equity, Venture Capital and Hedge Funds. It is often governed by a percentage share (which may change over time) of the overall ‘carry pool’ generated by the fund or firm. Given the option-like nature of Carry,[[7]] it can be large and may amount to an individual’s largest single form of remunerative benefit in any one year, or over a given period of time.

As we flagged at the outset, many would argue that Carry is not really a form of deferred compensation, but rather a performance linked profit-sharing arrangement to reflect excess returns generated by the investment professional. It most commonly takes the form of a performance-contingent fee, expressed as a percentage of a return on an investment or fund above a certain benchmarked annual level, compounded annually (typically referred to as the ‘Hurdle Rate’). If the Hurdle Rate is not met, then no Carried Interest entitlement will arise.

By way of a (simplified) worked example, if a fund raises capital for investment with a target rate of return for investors of, say, 8% and an entitlement to Carry of, say, 20%, then 20% of any returns over 8% will be shared by the employees and partners of the investment firm or Hedge Fund that are entitled to Carry. Let us say that ‘Fund A’ raises £100 million from investors and invests it with the same criteria as set out above (8% Hurdle Rate, 20% Carry entitlement). After three years, Fund A is worth approximately £140 million, representing an investment return equivalent to approximately 12%. In this scenario, the total Carry pool entitlement for Fund A would be equal to approximately £2.9 million.[[8]]

How is it valued?

Given the option-like nature of Carry, its valuation can be highly complex. It may require expert forensic accountancy evidence and much will depend on the investment stage of the fund.

On the one hand, the fund in which an individual holds an entitlement to Carry may be well established, with a long-documented track record of investment performance. In such scenarios, and especially where the fund is reaching the end of its life, an indication of the value of any Carry to be received may be undertaken by reference to a simple algebraic equation along the lines of:

(1) current value of fund; less

(2) the implied value of the fund, had it only achieved its Hurdle Rate; multiplied by

(3) the investment fund’s entitlement to Carry; multiplied by

(4) the individual’s percentage share of the total Carry Pool

On the other hand, there can be significant uncertainty as to the potential value of future Carry where a fund is newly formed and its investments are at the beginning of their life cycle. In our experience, in these circumstances investment professionals who hold entitlement to Carry in early-stage funds can be unwilling to place any value on its potential receipt at some stage in the future, citing the significant uncertainty that accompanies it.

Nonetheless, a reliable estimation of Carry is still necessary for the purposes of financial remedy proceedings and there are options available to the parties in such scenarios. One method is computational modelling, sometimes referred to as Monte-Carlo simulation. This allows for tens of thousands (or more) of simulations to be run, using parameters and inputs based on historical investment returns generated by the fund (or other similar funds) and the wider markets in which the fund invests. With these multiple simulations, a probability distribution can then be generated to allow for conclusions to be drafted to varying degrees of confidence, in the form of: there is an X% chance that Carry of between £Y million and £Z million will be paid out.

It goes without saying that this type of financial modelling is complex and, as with the more rigorous approach to valuation of Options, it will not be appropriate for all cases. It also requires forensic accountants and business valuation experts with specific experience in preparing and analysing such computational models. Nevertheless, very substantial sums might be at stake when Carry is in issue, so this kind of expert evidence may be necessary.

At the time of writing, carried interest is generally taxed at capital gains rates in the UK. However, the tax treatment of carried interest is a controversial topic and is beyond the scope of this article.

Specific considerations…

As should be clear, cases involving carried interest entitlements will require considerable care.

Readers should be aware that if the hurdle is met in one year, but the fund underperforms in subsequent years, a scenario can arise where the recipient may have to pay back some or all the carried interest they have received to date. This is known as a ‘clawback provision’. This can mean that a recipient’s final entitlement may only be known at the end of a fund’s lifecycle. Carried interest often vests over a number of years, and sometimes only at the closing of a fund.

When identifying the ‘shareable’ matrimonial element of an as yet unvested Carry entitlement, Mostyn J has recently endorsed a straight-line apportionment as a possible appropriate method in A v M [2021] EWFC 89. He set out his workings with characteristic clarity at [15] – the marital portion of the Carry was ‘C’, calculated as A/B (A being the period in months from fund establishment to date of trial, and B being the period of months from fund establishment to what he found to be the likely fund end date).

(4) Co-Investment

What is it?

Like Carry, we concede that Co-Investment is not, technically, a form of deferred compensation. Nevertheless, given its close relation and the frequency with which it occurs alongside other forms of Deferred Compensation, we address it here.

Co-Investment is exactly what it sounds like: a requirement that the ‘employee’ joins the ‘employer’ (often a partnership) by making a minority co-investment into the entity or fund which the employer manages and/or has invested in.

Again, like Carry, Co-Investment requirements are most common in certain areas of finance. In some cases, Co-Investment can go hand in hand with Carry entitlement, with Co-Investment being the required quid pro quo: the rationale being that it ensures that the employee (typically a senior partner or fund manager) has ‘skin in the game’. Those fund managers who have invested their own personal capital by way of Co-Investment will probably be highly incentivised to ensure that the venture is a success.

Co-Investment is often illiquid and rarely capable of extraction prior to the realisation of the entity or maturity of the underlying fund. The tax treatment of Co-Investment interests can be complex and specific advice should be sought, where necessary.

How is it valued?

Co-Investment typically follows the form of investments made into the fund. That is, Co-Investment receives a net return achieved by the fund manager, similar to that which an external investor might receive. However, the specific terms can vary from Co-Investment to Co-Investment in respect of whether Carry is deducted or what management fees, if any, are charged on the sums Co-Invested. As with other forms of Deferred Compensation, the employer and employee are often best placed to provide information on the current value of Co-Investment.

Specific Considerations

Where the principal investment is made from matrimonial funds, Co-Investment will often be treated by the court as a matrimonial asset. In B v B [2013] EWHC 1232 (Fam), Coleridge J described Co-Investment as ‘in the nature of capital saved out of annual income’. Wells sharing may be appropriate, or if a reliable valuation exists at trial (or settlement) it may be more appropriate to ‘cash out’ the recipient spouse from other liquid assets. If Co-Investment is to be Wells shared, there may be argument about a departure from equal sharing to reflect post-separation endeavour.

The law

For several years, the court’s approach to deferred compensation in financial remedy cases has been criticised as arbitrary and inconsistent. This article is being written today, in January 2022, in response to a handful of cases determined in the last few years at Court of Appeal and High Court level. The effect of these has been to make the court’s position on the treatment of deferred compensation as clear as it has ever been. That said, there is still a sizeable area of uncertainty, which needs to be navigated with caution.

In the following section, we:

a) Draw out propositions from the jurisprudence that constitute the court’s ‘general approach’ to deferred compensation; and

b) Discuss the main remaining points of uncertainty.

Basic propositions – the court’s general approach

(1) A party’s earning capacity cannot amount to a matrimonial asset subject to the sharing principle. For that reason, a maintenance order can only be made against income earned post-separation if required by need or (very rarely) to reflect an element of compensation.[[9]] Waggott [2018] EWCA Civ 727, SS v NS [2014] EWHC 4182.

(2) By way of exception, in some cases fairness may justify a bespoke percentage-based sharing of discretionary future cash bonuses. If reasonable needs cannot be fairly met from a maintenance award paid from basic salary alone, then it might be fair to apportion a receiving party’s reasonable needs between a budget for ‘ordinary expenditure’, and a further budget for ‘additional discretionary items which will vary from year to year’. The former might be met by periodical payments from basic salary. The latter might be met by a capped share of an annual discretionary bonus. The share must be capped to avoid inadvertent sharing of income. SS v NS, H v W [2015] 1 FLR 75.

(3) For the purposes of carrying out the computation exercise required by s 25, save in cases where there has been undue delay between separation and determination, assets are valued as at the date of trial. The court must attempt to place a notional value on all assets, including those asserted to be non-matrimonial, and elements of deferred compensation that have been earned but may not yet have vested or become payable. Cowan v Cowan [2001] 2 FLR 192, E v L [2021] EWFC 60.

(4) Unspent income (in whatever form) earned within the marriage should generally be treated as a matrimonial capital asset subject to division between the parties, even if its actual receipt is deferred and subject to continuing employment. Such compensation should generally not be shoehorned into the category of a future income stream if it has been earned within the marriage. That said, readers should note that there is an alternative opposing view that has been peripherally endorsed by the Court of Appeal, although in our experience it has been generally ignored. More on this shortly. SS v NS.

(5) The features of deferral and conditionality will often justify separate treatment. Deferral makes Wells sharing apt, and specific performance conditions (over and above simply continuing to turn up to work) might justify a departure from equal sharing. They may alternatively result in discounting at the computation stage, as discussed earlier in the article. SS v NS.

(6) Where such adjustment is appropriate, be wary of double discounting. Different judges have taken different approaches to whether difficulties in realisation should be reflected at the computation stage (by applying a discount to the valuation – see Mostyn J in WM v HM [2017] EWFC 25), or at the distribution stage (by departure from equal sharing – see Bodey J in Chai v Peng [2018] 1 FLR 248). That said, in Martin v Martin [2018] EWCA Civ 2866 (WM v HM on appeal), the Court of Appeal took the view that even where an asset is discounted at the valuation stage to reflect illiquidity/risk, the court might still assess that discounted value as having different ‘weight’ to the value of other safer assets like a matrimonial home. Moylan LJ said that this would not be to ‘take realisation difficulties into account twice’, but rather to acknowledge the ‘difference in quality between a value attributed to a private company and other assets’ which might be a ‘relevant factor when the court is determining how to distribute the assets between the parties to achieve a fair outcome’. Moylan LJ’s words in Martin appear to leave open the possibility of reflecting realisation difficulties at both the computation and distribution stage, although he emphasised this was not to ‘mandate a particular structure’…

(7) The question of whether a tranche of deferred compensation was earned inside or outside the marriage is one of fact. It is an important distinction. If earned within the marriage, subject to the points above it will probably be a matrimonial asset subject to the sharing principle. If it was earned post-separation, it is prima facie non-matrimonial property that should not be shared, but might be invaded if required to meet needs, or in very rare circumstances to reflect an engagement of the compensation principle. C v C [2019] 1 FLR 939.

(8) When assessing whether a tranche of deferred compensation amounts to non-matrimonial property, the court must conduct the three-stage exercise set out by Moylan LJ in Hart v Hart [2016] EWCA Civ 497. That is to (1) case manage appropriately to ensure the issue is properly dealt with, (2) make such determinations as the evidence permits, and (3) cross-check the arithmetical output of those determinations in a ‘holistic assessment of fairness’. In some cases it will be possible to draw a ‘clear dividing line’ to identify the perimeters of matrimonial and non-matrimonial property, in others a ‘more complicated continuum’ might exist, and the court will have to do its best with a broad assessment to carry over to the final discretionary stage. Hart, C v C.

(9) In those cases where the vesting period of a portion of deferred compensation straddles the date of separation and is subject to continuing performance conditions, a straight-line apportionment might be an appropriate tool to calculate the notionally matrimonial portion of the asset (subject always to the third, discretionary stage of the Hart exercise). This method plots the accrual of the asset as a straight line between £0 and its notional trial value over the period in which it is earned: the matrimonial portion is the section of the line falling within the marriage. This type of approach has been deployed by Mostyn J (twice) and Roberts J and has withstood scrutiny from the Court of Appeal. WM v HM, C v C,[[10]] Martin v Martin and A v M [2021] EWFC 89.

(10) Carried interest is properly viewed as a ‘hybrid’ species of asset – something between a return on a capital investment and an earned bonus with characteristics of both. Insofar as it has not crystallised at the point of separation, it will often be part product of matrimonial endeavour and partly the product of endeavours post-separation. Straight-line apportionment can also be an appropriate tool to calculate the matrimonial portion of an as yet uncrystallised carried interest entitlement, as discussed above. A v M, B v B [2013] EWHC 1232 (Fam).

(11) Wells sharing of deferred compensation (including carried interest entitlements that have yet to fall in) may be appropriate. However, Wells sharing has fallen out of favour with the Court of Appeal in recent years and is thus to be limited where possible. A v M, SS v NS, Versteegh v Versteegh [2018] EWCA Civ 1050.

Capital or future income stream?

At point four above, we say that unspent income earned during the marriage, including in the form of unvested deferred compensation, should generally be treated as a capital asset rather than a future income stream. There is an alternative school of thought. In Lawrence v Gallagher [2012] EWCA Civ 394, Thorpe LJ treated deferred compensation as a future income stream rather than capital. At first instance, Parker J had awarded the wife a 45% Wells share of unvested deferred bonuses earned during the marriage (albeit she wrongly believed them to be vested). She described them as ‘part of the assets acquired during the partnership’. Thorpe LJ overturned this aspect of Parker J’s judgment, saying at [52] ‘these were bonuses deferred in collection and conditional on performance. They were not capital assets but part of the appellant’s income stream upon which he is taxed at top rate’.

Mostyn J was highly critical of this approach in SS v NS and said at [12] of his judgment that there would have to be ‘special features present’ before earned but deferred monies/assets were excluded from the divisible pool. Mostyn J’s approach has generally been followed by other High Court judges, including Roberts J in C v C and Francis J in O’Dwyer v O’Dwyer [2019] EWHC 1838 (Fam). In O’Dwyer Francis J said at [28] of his judgment ‘if a bonus is earned during the marriage but not paid out until after the marriage has ended then there is every reason to treat it as matrimonial property in the true sense’.

Lawrence v Gallagher is difficult to sweep under the proverbial carpet. It is a Court of Appeal authority, and Thorpe LJ’s treatment of the deferred compensation, whilst case-specific, cannot be dismissed as obiter. Lawrence v Gallagher came before the Waggott watershed, where a much clearer line was drawn between capital and income. That said, in XW v XH [2019] EWCA Civ 2262, a husband had been awarded £28m of RSUs and Options during the marriage, which were largely unvested at the date of the trial, although for a significant proportion vesting was only contingent on continued employment (and not specific performance). At first instance, Baker J (as he then was) excluded all the RSUs and Options from division, as Thorpe LJ had done in Lawrence v Gallagher.

This specific element of the judgment was challenged on appeal. The authors understand that the court was referred to the tension between SS v NS and Lawrence v Gallagher in submissions.[[11]] The Court of Appeal declined to overturn that element of Baker J’s judgment and dealt with the point very briefly at [165]. Moylan LJ noted that ‘although the judge dealt with the RSUs and options very briefly’, he had ‘not been persuaded that he was wrong to decide that they were “dependent on future performance” and should, therefore, be “disregarded”. This was a decision which he was entitled to reach and takes them outside the scope of marital property’.

Where does that leave us? Despite the conspicuously cursory manner with which the point was addressed, we do not think XW v XH necessarily endorses the treatment of unvested deferred compensation granted during the marriage as a future income stream. The Court of Appeal simply declined to interfere with Baker J’s exclusion of the deferred compensation from division. Whilst the Lawrence v Gallagher approach (income rather than capital) appears to have been largely ignored in practice, the assessment will always be fact specific. As Mostyn J accepts – ‘special features’ in a given case might justify such treatment. In our experience Mostyn J’s characterisation in SS v NS is far more commonly adopted by judges and practitioners alike.

‘Run off’ – still a sound concept?

Waggott closed the door on any residual misapprehension that an earning capacity can be subject to sharing. As noted by Roberts J in C v C, the logical consequence of the Waggott principle was to exclude post-separation earnings from the reach of the sharing principle. This applies whatever form those post-separation earnings might take (cash savings, investments or ‘any tangible accretion to future capital wealth’). It is thus pertinent to the treatment of deferred compensation.

There is a problem. There are three pre-Waggott High Court level authorities that appear to endorse some limited sharing of post-separation income. These are Rossi v Rossi [2007 1 FLR 790, H v H [2007] 2 FLR 548 and to a lesser extent CR v CR [2008] 1 FLR 323.

In Rossi, Nicholas Mostyn QC (then sitting as a deputy High Court judge) opined that an asset representing the proceeds of a bonus or other earned income should not be properly classified as non-matrimonial unless it related to a working period which commenced at least 12 months post-separation. He acknowledged an ‘element of arbitrariness’ in his proposed cut off point. He approved a point made previously by Coleridge J, which is that ‘during a period of separation, the domestic party carries on making her non-financial contribution but cannot attribute a value thereto which justifies adjustment in her favour’. This proposition was explicitly rejected by Roberts J at [40] of her judgment in C v C as a justification for sharing post-separation income:

‘Whatever regime was then put in place by the parties in relation to their mutual and ongoing contributions to their children’s welfare and the financial support of the family, it was not an ongoing marital partnership. For this reason, and absent arguments about needs and compensation, I do not accept the wife’s proposition that her ongoing contributions to the general welfare of the family matched those of the husband’s and/or gave rise to any entitlement to an equal share in the husband’s post-separation earnings. However, and it is an important caveat, that does not necessarily mean that those contributions were, or are, irrelevant as part and parcel of the over-arching circumstances of the case in terms of an assessment of needs or fairness of outcome.’’

In H v H, Charles J decried the 12-month post-separation cut-off approach adopted in Rossi as arbitrary and lacking ‘regard to the realities and circumstances of a given case’. Charles J instead awarded the wife decreasing uncapped percentages of the husband’s bonuses earned in the three years post-separation (1/3rd, 1/6th, and 1/12th). He described this as a ‘run off’ award. One might consider his approach to be more arbitrary than that in Rossi. He said at [111] of his judgment:

‘To my mind it is in particular the concept of an award in respect of the loss of a share in the enhanced or greater income or earning capacity created by the contributions, lifestyle and spadework of the parties during the marital partnership, and thus an award in respect of that fruit or product of the joint endeavours of the parties during the marital partnership, that provides the answer to the general question. In my view that rationale could be classified as either compensation or sharing.’

Waggott renders the reasoning at [111] of Charles J’s judgment completely unsustainable. A spouse has no entitlement to share in the post-separation fruits of an earning capacity, even if said earning capacity was built during a marriage.

In CR v CR, Bodey J made a £9m award to a wife out of a £16m asset base. The £1m departure from equality was justified by including a £5m Duxbury fund within the wife’s award (in addition to her retention of the family home and a holiday home at £4m aggregate). Bodey J made clear that he intended within his award to give some recognition to the ‘big income imbalance’ between the parties going forward: the product of an earning capacity assisted by the wife’s ‘past contributions’. That said, Bodey J’s award was nonetheless predicated on a generous assessment of the wife’s future needs and a determination that it was unfair for her to amortise her non-Duxbury capital when the husband would have recourse to his substantial future earnings. Whilst generous, Bodey J’s approach was ultimately pinned to needs. When viewed retrospectively, it probably doesn’t fall foul of the Waggott principle.

All three of these cases were referenced in Waggott, not least because Mr Waggott himself had offered Mrs Waggott a declining share of post-separation bonuses: a ‘run off’. Macdonald J raised these authorities with the husband’s counsel as anomalies. Nigel Dyer QC for the husband explained Mr Waggott’s offer of ‘run off’ as an ‘example of pragmatism, namely the goal of achieving an end resolution’. The Court of Appeal applauded this aim but asked whether any of the three ‘run off’ cases supported the proposition that the post-separation fruits of an earning capacity could be shared. It answered its own question at [122]: ‘the clear answer is that it is not’.

The Court of Appeal did not go so far in Waggott as to say that the three ‘run off’ cases had been wrongly decided. Nonetheless, post Waggott and C v C, many thought that the notion of ‘run off’ was dead, and that the approaches deployed to share post-separation earnings in Rossi and H v H had been disapproved and consigned to history. However, in E v L [2021] EWFC 60, Mostyn J re-affirmed his Rossi approach of drawing the non-matrimonial income boundary line at an earning period commencing no less than 12 months post-separation.

On one level, one can see how it is difficult to draw a ‘clear dividing line’ where an annual tranche of compensation (in whatever form) is granted by reference to an earning year overlapping with the marriage. That said, in E v L, Mostyn J refers to ‘earnings made during separation’ and not just annual bonuses/compensation awards. Does Mostyn J intend the same approach to apply to the residual proceeds of monthly salary income earned up to 12 months post-separation? If so, wouldn’t that incentivise an earning party to spend at a higher level to avoid paying their ex-spouse half of any savings made from income earned post-separation? What of clear breaks in an employment continuum? Hypothetically, would a sign-on bonus received on commencement of an entirely new role within 12 months of separation fall subject to sharing?

The idea that the sharing principle applies to all proceeds of income accrued within one earning year of separation is difficult to reconcile with Waggott. It creates an artificial one-year grace period in which the Waggott principle does not apply. Further, even in relation to annually granted tranches of compensation, the linear apportionment approach discussed and illustrated earlier in this article seems a more rigorous analysis. Remuneration is not ‘banked’ at the beginning of a financial year – it is accrued over the course of the earning period. Hart obliges the court to make such factual determinations as the evidence permits. A straight-line apportionment of annual compensation referable to a period straddling separation is a straightforward calculation and may be an appropriate tool with which to carry out the second stage of the Hart exercise.

Our view is that caution is required where this point arises. Those seeking to share the fruits of income earned proximately post-separation will cite Rossi and E v L in support, those resisting will cite Waggott and C v C. Waggott is obviously the higher binding authority, and it is telling that the Court of Appeal dealt with Rossi head on and withheld endorsement of its approach. The extent to which the Rossi/E v L 12-month grace period can be reconciled with the ratio of Waggott is a matter for debate.

[[1]]: We do not include cash bonuses as deferred compensation.

[[2]]: ‘Promote payments’ are similar in structure to Carry and are often used in Real Estate finance.

[[3]]: Such shares are sometimes separately classified as ‘PSUs’ (Performance Stock Units).

[[4]]: Although there is conflicting authority on the point – see the discussion below about Lawrence v Gallagher, SS v NS and XW v XH.

[[5]]: For ‘European’ options, the exercise date and the expiration date are one and the same. However, financial options are an exotic equity instrument and can take a myriad of forms, the discussion and explanation of which is beyond the scope of this article.

[[6]]: Fischer Black was ineligible for the prize as it is not awarded posthumously, following his death in 1995.

[[7]]: By ‘Option-like’, we mean that in certain scenarios, where the required performance metrics are achieved, Carry can be large, whereas in situations where the Hurdle Rate is not met, its value will be nil.

[[8]]: 20% x ((£100 million x (1 + 12%)3) – (£100 million x (1 + 8%)3) = £2.9 million.

[[9]]: That is, the compensation principle birthed by Miller; McFarlane and explored recently by Moor J in RC v JC [2020] EWHC 466 (Fam).

[[10]]: It seems that Roberts J endorsed a version of this approach in C v C, although the precise methodology is not entirely clear from the judgment. It appears from paragraphs [19], [52] and [54] that each tranche of the husband’s RSUs was subject to a 56-month ‘earn-out’ period. Applying this ‘formula’ to the RSUs the husband calculated the matrimonial portion of both vested and unvested RSUs.

[[11]]: Although they are not referred to in the list of authorities relied upon in the Family Law Report…