Fair Shares Supplementary Reports: An Overview

Following the Fair Shares Report, additional analysis was undertaken on the dataset, resulting in four supplementary Reports. This article provides a summary of the findings from these additional Reports, drawing out some of the key issues going forward with regards to policy and practice.

Introduction

The Fair Shares Report,[[1]] published in November 2023,[[2]] provided a comprehensive overview of the financial settlements that people make on divorce. It is the first fully representative study in England and Wales to examine those arrangements. An overview of the key findings from the main Report can be found in the Spring 2024 issue of this Journal[[3]] whilst a more detailed outline of the study’s methods and aims can be found in the Spring 2023 issue.[[4]]

Following that Report, additional analysis was undertaken on the dataset, resulting in four supplementary Reports. This article provides a summary of the findings from these additional Reports, drawing out some of the key issues going forward with regards to policy and practice.

What happens in cases involving domestic abuse?

The findings in this Report[[5]] were based on a subset of the Fair Shares dataset. This includes the responses of 670 divorcees who reported in the survey that the abusive behaviour of their ex-spouse was a reason for the breakdown of the marriage, and interview data from 12 divorcees who experienced abuse during the marriage.

Whilst the main Fair Shares report provided evidence that women with children and those in older age tend to come out of divorce poorly compared with men, the supplementary report highlighted the particular financial vulnerability faced by female survivors of domestic abuse. Not only were female survivors of domestic abuse, on average, entering divorce in more vulnerable financial positions than other women,[[6]] but they also often continued to be in more precarious financial positions following divorce.[[7]] Taken together, these findings demonstrate the particular financial risk that this group of divorcees face when getting divorced compared with other female divorcees, with potentially less capacity to support themselves financially after divorce, particularly given that domestic abuse was more common among women with dependent-age children,[[8]] with the added financial burdens and constraints that childcare brings.

Despite having fewer financial assets, the research also showed how both male and female survivors of domestic abuse were not only more likely than other divorcees to have incurred legal or mediation costs in sorting out their finances on divorce, but they were largely shouldering the legal services bill themselves rather than receiving legal aid – with fewer than one in five accessing this. This is despite domestic abuse survivors being – subject to means-testing – entitled to seek legal aid for finance matters on divorce if they meet one of the prescribed evidence requirements. These low levels of legal aid awarded to domestic abuse survivors and the costs incurred by them highlight the issues surrounding the low capital and income thresholds for survivors and raise serious questions about the need to increase these so that the most vulnerable have access to legal support and advice.

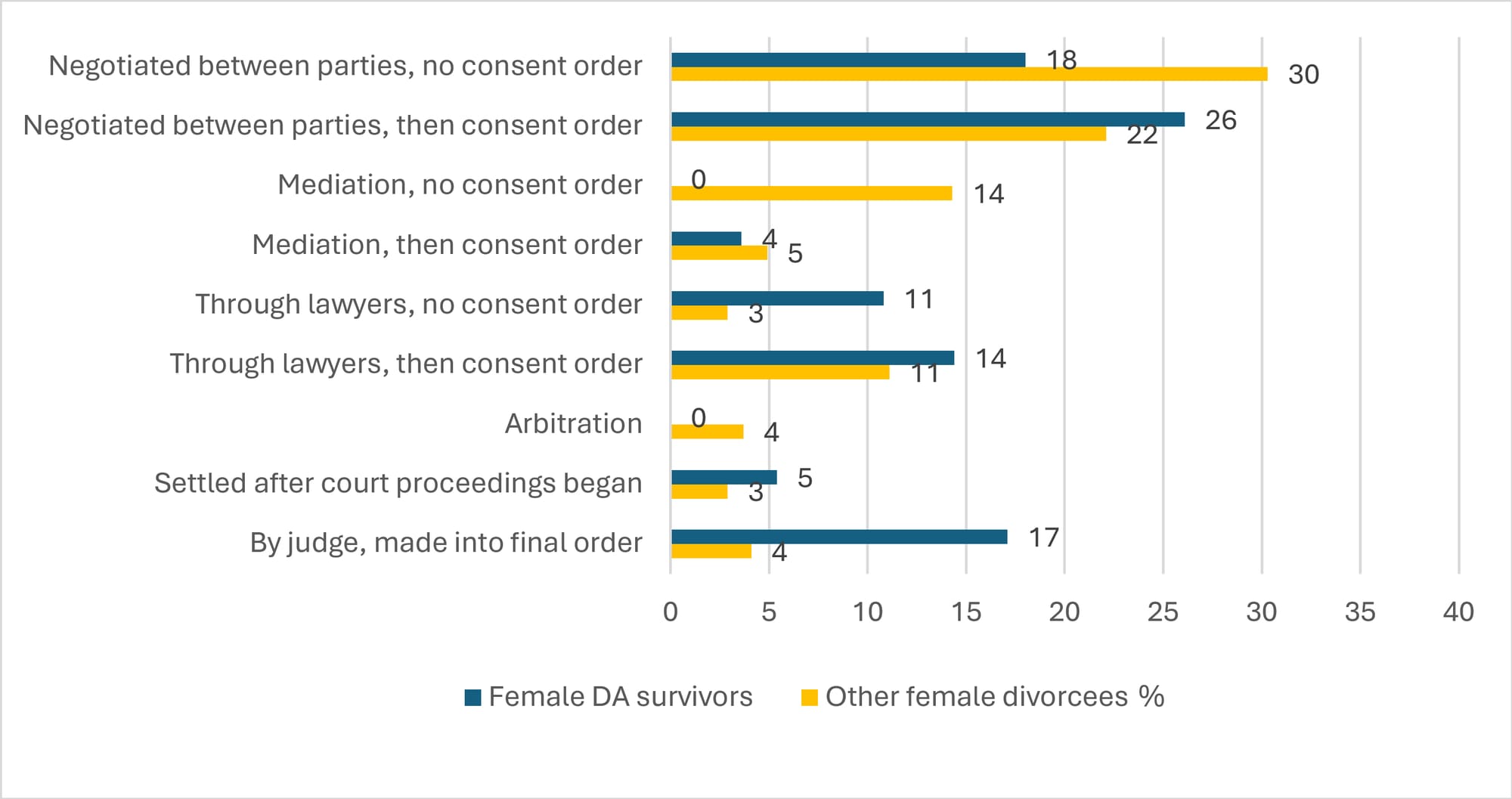

The research also highlights the vital role of the formal legal process for survivors of domestic abuse. As Figure 1 shows, the use of the non-court option of mediation was successful for only 4% of female survivors who reached a financial settlement compared to 19% for other female divorcees. However, the formal justice system was more likely to be used by female survivors to achieve a financial arrangement, with 17% of female survivors with a financial settlement reporting that their case had been determined by a judge, compared to only 4% for other female divorcees.

Figure 1: Method by which financial settlements were reached

Bases: female survivors of domestic abuse (257) and other female divorcees (499) with an arrangement.

Whilst the changes to the Family Procedure Rules to ensure that courts encourage parties to undertake non-court dispute resolution (NCDR) is a positive development for most couples, the Fair Shares additional findings provide a note of caution in relation to domestic abuse survivors. The fact that survivors are accessing the court and legal advice in higher proportions than other divorcees, with few survivors coming to agreements using mediation, suggests that many survivors want – and need – legal advice and support as well as robust judicial oversight and intervention. Given the low levels of successful mediation for domestic abuse survivors, any additional compulsory period spent on this form of NCDR may simply exacerbate existing vulnerabilities and power dynamics in these cases, and result in more costs being incurred as a result of the delay in the case reaching a judge. It is particularly important here to note that domestic abuse survivors in this study were more likely to report feeling that their ex-spouse had the most say when coming to the financial arrangement. Indeed, if unequal power dynamics – effectively a continuing form of controlling behaviour post-divorce – and non-disclosure are hampering any true negotiation, reducing opportunities for survivors to have their ‘say’ in any outcome reached, survivors may succumb to pressure to agree out of court and end up with a potentially poor settlement. Therefore, we suggest that a considerable degree of caution is required when reflecting on the appropriate family justice process for domestic abuse survivors, particularly in light of the current policy drive towards NCDR.

Child arrangements and financial settlements

In England and Wales, the issue of shared care has become particularly pertinent since the introduction of the presumption of parental involvement in the Children Act 1989.[[9]] However, financial arrangements are rarely discussed in the shared parenting debates, particularly in relation to how finances and property on divorce are divided and the approaches and attitudes of these parents to financial and property division.

Even beyond issues of shared parenting, there is a general lack of evidence about the ways in which child arrangements and financial settlements are made alongside each other, who is making them and why they are doing so. This is a particular issue given the strong policy priority of private ordering of family disputes. Without robust evidence regarding how negotiations and arrangements are arrived at and managed outside the courts and Child Maintenance Service, with or without legal advice, there is no firm evidence base from which policy makers can discuss and assess what changes might be required.

The findings in this Report[[10]] were based on a different subset of the Fair Shares dataset, drawing on the responses of 1,189 survey participants and 26 interviewees who had dependent-aged children with their spouse at the time they divorced.

An important backdrop to understanding how parents with different child arrangements navigated the financial aspects of the divorce process are the factors they took into account during any negotiations. This is particularly important within a family justice system which is discretionary and where many divorcees make financial arrangements outside the formal legal system. Putting their children’s needs first was a priority for many divorcing parents – regardless of their child arrangement – both when considering what they wanted from a financial arrangement and when reaching any financial settlement. Furthermore, all parents, irrespective of child arrangement type, commonly cited that what they wanted from a financial arrangement was stability for their children, particularly emotional stability, educational stability (schooling), social stability (friends and hobbies) and housing stability, with housing stability being a particularly important motivation for parents who had greater day-to-day responsibility for their children.

The fact that many parents focused so strongly on placing their children’s needs at the centre of their decision-making is an important finding given the current focus of the law with the first consideration being the welfare of any children of the family under s 25 Matrimonial Causes Act 1973. The parents in the Fair Shares study, within the context of often constrained financial circumstances at the point of divorce, limited legal advice, and negotiation of their financial arrangements outside the formal legal sphere, appear to be making decisions which accord with this aspect of the current legal framework.

In addition, we found a clear difference in both the process of achieving the financial arrangement and the content of the financial arrangement between parents with differing child arrangements. Where both parents had equal time care, there was often a more informal process to reaching a financial arrangement and a tendency towards more equal financial outcomes. For example, among those with equal time care, more parents had divided their assets more closely to 50:50. Parents with equal time care were more likely than other parents to have a pension sharing agreement and there were more 50:50 splits of savings and debts. In terms of process, a high proportion of those with equal time care had negotiated a financial settlement themselves and, compared with other parents, were less likely to have involved lawyers (and, consequently, had spent less on legal costs on average than resident parents). However, it is important to note that parents with equal time care came from marriages with higher household incomes and with a greater level of assets, compared to families where one parent became the main carer.

Where one parent had the main care of the children, resident parents were more likely than other parents to engage a lawyer at some point during the divorce process, often related to perceived difficulties in dealing with their ex-spouse. For those who used a lawyer throughout, roughly twice as many resident parents compared with non-resident parents said that they did so because they did not feel comfortable negotiating with their ex-spouse. For resident and non-resident parents who did not use a lawyer at all or for only part of the process, fear of costs was a major factor in not doing so. These findings suggest that unlike equal time care parents, resident and non-resident parents found it more difficult negotiating with their ex-spouse and needed more support during the divorce process.

In terms of the financial arrangements for those without equal time care, on average, resident parents received more than non-resident parents, particularly in the case of low value divorces, and to some extent among high value cases. However, for parents with mid-value assets, the division of the assets between resident and non-resident parents was more equal. Perhaps, in these cases, the negotiation and ensuing arrangement was more a fine balancing act given the other assets that may be in play in a middle value case (i.e. pensions, savings and debts). If transfer of the former matrimonial home takes place (which the findings show is common), then offsetting that transfer with pension assets or attempting to find a compensatory amount to enable the other parent to rehouse may mean a more difficult balancing act for parents in the mid-asset case.

Although equal time care parents were more likely to have split their assets more equally, it does not mean to say that such financial arrangements are appropriate for other parents. Neither do these findings suggest that encouraging equal time care child arrangements across all parents should be the way forward. On the contrary, the findings outlined here merely highlight the process and financial implications for a small group of generally wealthier parents who appear to have a relatively amicable ongoing relationship, albeit with some ongoing communication issues.

Regional disparities in spousal maintenance

In order to properly evaluate the advantages and disadvantages of whether there should be a maximum term limit for spousal periodical payments,[[11]] it is vital to understand the extent to which spousal periodical payments are being made at all, whether spousal periodical payments are more prevalent in certain areas compared to others, and the reason(s) why spousal periodical payments are (not) being ordered. This is important as policy-makers have previously expressed concern about regional disparities in the prevalence of spousal support apparently being awarded by different courts.[[12]]

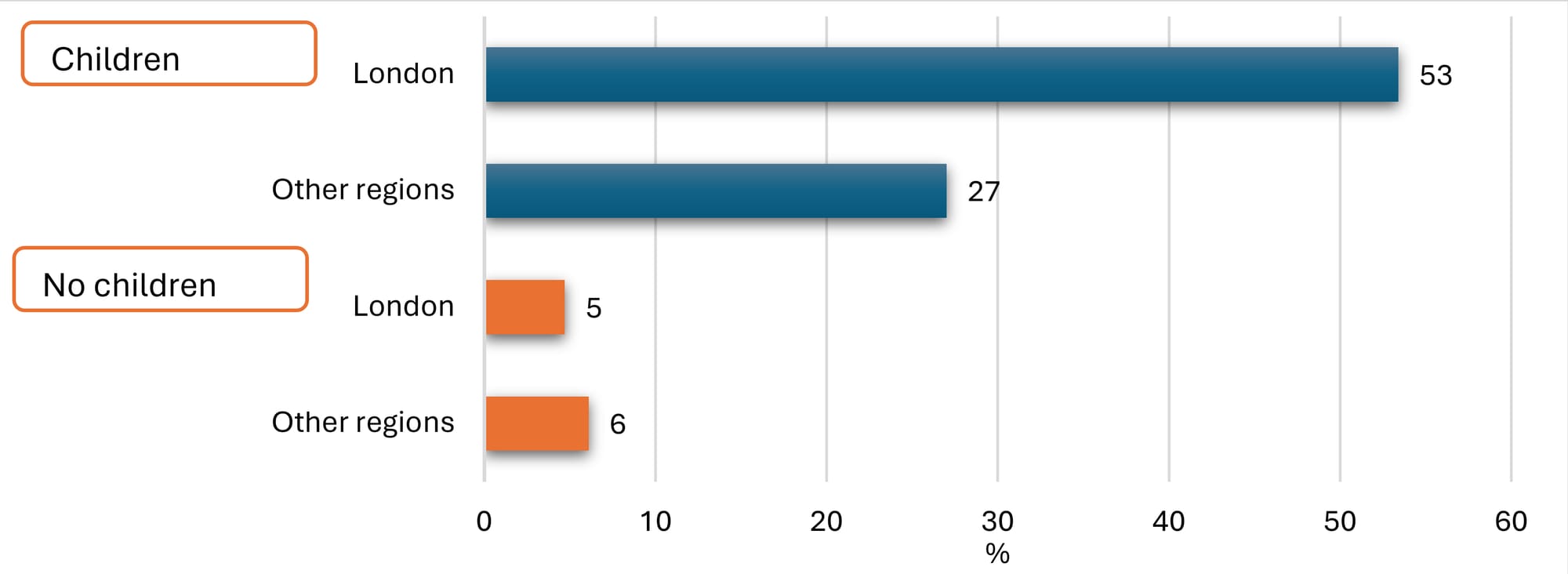

The key finding from the short supplementary Report[[13]] examining regional disparities in spousal maintenance was that spousal maintenance arrangements are much more common in London than elsewhere. Figure 2 shows the percentage of divorcees in London and elsewhere with a spousal maintenance arrangement at the point of divorce, split into those with and without (dependent or non-dependent) children with their ex-spouse. The ‘London difference’ only applies to spousal maintenance for parents, where half (53%) of parents had a spousal maintenance arrangement compared to a quarter (27%) of parents in other regions. The prevalence rate among divorcees without children were low in London and other regions. These findings are particularly noteworthy and provide robust evidence to demonstrate the correlation between the payment of spousal maintenance and having children. They emphasise the link between such payments and the associated needs arising from taking, or having taken, primary care of any children of the relationship.

Figure 2: Percentage of divorcees with a spousal maintenance arrangement at the point of divorce, by whether or not the divorcees had children with their ex-spouse, London versus other regions

Bases: children: London (152); other regions (1,326); no children: London (74); other regions (842).

The higher prevalence rates of spousal maintenance in London compared to elsewhere are present regardless of the level of wealth. Covering the recipient’s ongoing needs, particularly housing costs in areas where housing is expensive, is particularly noteworthy in light of Jennifer Buckley and Debora Price’s important analysis of pension and former matrimonial home wealth by geography.[[14]] Their findings show ‘the distorting effect of property prices in London’.[[15]] They found that outside London and the South East, the pension is usually the largest asset for the 40% of couples with greatest pension wealth, whereas in London in particular, very high housing costs make the former matrimonial home much more valuable. This specific geographical issue with regards to high housing costs, may well be a key factor leading to the regional disparity in spousal periodical payments, with the primary carer more likely to need spousal periodical payments to pay a mortgage on the existing or new family home, or to help towards rental costs.

The other important findings relate to the use of legal support and obtaining a formal court order. Among those who had used a lawyer in relation to their finances and among those who had come to a formal financial arrangement, the number of spousal maintenance arrangements was markedly higher in London than elsewhere. Among those who used a lawyer, almost three times as many divorcees in London had a spousal maintenance arrangement than in other regions (60% compared to 22%), and among those who had a financial order, rates of spousal maintenance were twice as high in London as in other regions (56% compared to 23%). Whilst it is unsurprising that spousal maintenance arrangements were common where a lawyer had been used and where orders had been made, what is more interesting is that there was still a London difference amongst those who had not used a lawyer, albeit not as large, with 32% of those who had not used a lawyer with a spousal maintenance arrangement compared to 18% in other regions. Likewise, among those with an arrangement which had not been made into an order, the rates in London were significantly higher than in other regions (46% compared to 25%).

Put together, these findings suggest that, while the ‘London difference’ may be partially explained by the use of legal support/advice and the use of formal court orders taken to reach a financial agreement, there are other factors at play. One potential factor – which would be particularly pertinent to the needs associated with having children, and especially being the resident parent – are the higher living costs in London. The data provides evidence of divorcees in London paying spousal maintenance to meet their ex-spouses’ ongoing needs, whether that is through paying a mortgage or other household bills. A second potential factor might be a particular London legal culture, where legal advisers in London are more likely to suggest spousal maintenance because the combination of the higher costs of living and higher incomes they often deal with have led to a particular need for spousal maintenance. Of course, this would not directly address why those without legal support or without a court order are still more likely in London to have spousal maintenance, but this may be due to the effect of receiving information or advice from friends or family based on the local context and experience, as well as the higher costs of living in the capital.

So, to answer the question whether geographical inconsistency is limited to the courts: this is not clear cut. There appears to be some link with formal orders, but geographical inconsistency also occurs in arrangements with no orders. Therefore, in light of the finding that the ‘London difference’ is present among those who did not have legal support, those who did not obtain a court order, and across divorces with higher and lower levels of assets, we suggest that there are other factors at play. Instead, a key underpinning factor is the parties’ needs, especially related to the needs associated with being the primary carer of dependent children or having been the primary carer of children.

Public understanding of the law

Despite the fact that the statutory framework governing the financial consequences of divorce has (largely) existed for 50 years, surprisingly little is known about the public’s understanding of the current law around finances and property on divorce. The final supplementary Report presented findings on people’s understanding of the current law.[[16]] This included understanding demonstrated among both the general public in England and Wales, and those who had experienced a divorce in the previous 5 years.

It is important to know about the public’s understanding of the law, given that, as Pleasance et al suggest, ‘erroneous beliefs are likely to prove stubborn to dislodge’.[[17]] By no means will everyone personally experience divorce, but most people will be the family member or friend of someone who does. We know from the main Fair Shares Report that the majority of the divorcing population reach arrangements relating to their finances and property outside the formal family justice system, and also that one in five (19%) divorcees sought advice and support from family and friends during the divorce process.[[18]] For these reasons, it is important to know what level of knowledge people have, and whether there are misconceptions which might be influencing the decisions made by divorcees and the advice that family and friends provide.[[19]] This is particularly important in a context in which access to legal aid for private family law disputes in England and Wales has been severely curtailed.[[20]]

In addition to our findings about the awareness of the general public, it is valuable to gauge divorcees’ awareness of what the law is (or is not) because, as the Mapping Paths research found, uneven levels of knowledge, and parties bringing their own norms to dispute resolution, can make it difficult for divorcing couples to come to an arrangement.[[21]]

The Report drew on 10 survey questions designed to gauge people’s understanding of the current law of financial remedies. The questions involved presenting survey participants with 10 statements[[22]] – and asking them to say whether they thought each was ‘true’, ‘not true’ or that they did not know. The questions were fielded among a representative sample of 20,532 members of the general public living in England and Wales[[23]] and among the 2,415 divorcees included in the main Fair Shares survey.[[24]]

The public got an average (mean) of 4.5 of the 10 statements correct (i.e. correctly identified them as true or false). Just over half (55%) of the public got at least half (five or more) statements correct, with only 1% getting all 10 correct. In contrast, 11% got none correct.[[25]]

This low level of understanding also applied to those who had divorced in the previous 5 years, although divorcees were somewhat more knowledgeable about the law than those who had not been through a divorce. Divorcees identified an average of 5.2 statements correctly compared to 4.4 statements among those who had not been through a divorce. Divorcees who had consulted or used a lawyer, those who had used more formal routes to reaching an arrangement, and those who had more assets to divide tended to have a greater understanding. Furthermore, divorcees with dependent children were more knowledgeable than other divorcees in relation to the law around the legal position of parents with main care of their children and around the child maintenance formula, although there were still high levels of misunderstanding among parents on these issues.

Therefore, these findings show that there is a generally poor and patchy understanding of the law relating to finances on divorce amongst both the general public and divorcees, and that this presents a particular challenge when it comes to potential law reform.[[26]] With most of the divorcing population remaining ‘outside’ the formal family justice system and not accessing legal services in relation to their financial arrangements, questions arise not only about the effect that any future law reform may have on such divorcees, but also how (updated) legal information should be provided to couples who appear to be bargaining outside the ‘shadow of the law’.[[27]] As noted by one of us previously, divorcees ‘are increasingly reliant on themselves, their own (in)ability to settle their family dispute, and […] their own (mis)understanding of family law’.[[28]] Some form of early legal advice and information for all divorcees should be a policy priority as this could help to address the deficit in knowledge about the law and legal procedure among the divorcing population, particularly amongst those divorcees who do not obtain any form of legal support.

Concluding thoughts

The Nuffield-funded Fair Shares research project has now come to an end, with the supplementary Reports providing a range of policy and practice thoughts, as well as suggestions for further research. Over each of the five Reports, the collective findings have provided the first representative picture of the financial arrangements on divorce across the divorcing population in England and Wales, providing insights into a range of issues of relevance within the financial remedies field. In particular, we hope it has shone a much needed light on the ‘everyday’ financial remedy case whilst also emphasising the importance of considering the entire breadth of the divorcing population when it comes to practice, policy and process.

[[1]]: The Fair Shares project was funded by the Nuffield Foundation, but the views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily the Foundation. Visit www.nuffieldfoundation.org

[[2]]: E Hitchings, C Bryson, G Douglas, S Purdon and J Birchall, Fair Shares? Sorting out money and property on divorce (University of Bristol, 2023).

[[3]]: E Hitchings, C Bryson and G Douglas, ‘The financial reality of the “everyday” divorce’ [2024] 1 FRJ 14.

[[4]]: E Hitchings, C Bryson, G Douglas, S Purdon and J Birchall, ‘Fair Shares? Sorting out money and property on divorce’ [2023] 1 FRJ 47.

[[5]]: E Hitchings and C Bryson, Dividing property and finances on divorce: what happens in cases involving domestic abuse? (University of Bristol, 2024).

[[6]]: They often had fewer assets to divide than other female divorcees (e.g. less likely than other women to have their own pension (55% compared to 62%)) and were also less likely than other divorcing women to have been working at the point at which they separated (24% were not working compared to 16% of other women). Among women who were working during the marriage, survivors were earning less on average than other women, with nearly twice as many survivors as other female divorcees earning under £1,000 per month after tax (39% compared to 22%).

[[7]]: For example, up to 5 years after their divorce, female survivors were less likely than other women to be in full-time paid work (44% compared to 56%), and more likely to be on Universal Credit (32% compared to 17%).

[[8]]: 61% of survivors compared to 52% of other female divorcees.

[[9]]: Children Act 1989, s 1(2A).

[[10]]: E Hitchings and C Bryson, Divorce among families with dependent-aged children: the interaction between child arrangements and financial settlements (University of Bristol, 2025).

[[11]]: One of the issues considered in the Law Commission’s Scoping Review, see https://lawcom.gov.uk/project/financial-remedies-on-divorce/

[[12]]: Law Commission, Matrimonial Property, Needs and Agreements, Law Com No 343 (2014), paras 2.45–2.53.

[[13]]: E Hitchings and C Bryson, Spousal maintenance across regions (University of Bristol, 2024).

[[14]]: Jennifer Buckley and Debora Price, ‘Pensions on divorce: where now, what next?’ [2021] 33(1) Child and Family Law Quarterly 5.

[[15]]: Buckley and Price, p 22.

[[16]]: E Hitchings and C Bryson, Understanding of the law around finances and property on divorce (University of Bristol, 2025).

[[17]]: P Pleasence, N Balmer and C Denvir, How People Understand and Interact with the Law (PPSR, 2015), p iii.

[[18]]: E Hitchings, C Bryson, G Douglas, S Purdon and J Birchall Fair Shares? Sorting out money and property on divorce (University of Bristol, 2023), section 4.6, pp 155–120.

[[19]]: Certainly, there is evidence of other public misconceptions about the rights of separating couples. Barlow et al (2008) found that the common law marriage myth was widespread, with a lack of legal awareness demonstrated among cohabiting couples. See A Barlow, C Burgoyne, E Clery and J Smithson, ‘Cohabitation and the law: myths, money and the media’ in Alison Park et al, British Social Attitudes – The 24th Report (Sage, 2008), pp 29–51.

[[20]]: Legal aid (public funding for legal services) was withdrawn for most private family law proceedings by the Legal Aid, Sentencing and Punishment of Offenders Act 2012, although it remains available for mediation.

[[21]]: A Barlow, R Hunter, J Smithson and J Ewing, Mapping Paths to Family Justice: Resolving Family Disputes in Neoliberal Times (Palgrave, 2017), pp 196–204.

[[22]]: Given the discretionary nature of the law, some of the statements were generalisations of the legal position. See p 4 of the Report (n 16 above) for a list of the statements used.

[[23]]: These were asked of YouGov’s nationally representative online panel during the process of screening for people who had divorced within the previous 5 years to take part in the main Fair Shares survey. The sample was weighted to ensure it represents the population.

[[24]]: These two samples are not completely distinct as a subset (380) of the divorcees (the nationally representative element) are also present within the general public sample. For a full account of the methods used in the study, see E Hitchings, C Bryson, G Douglas, S Purdon and J Birchall, Fair Shares? Sorting out money and property on divorce (University of Bristol, 2023), ch 2.

[[25]]: 21% got between one and three statements correct; 28% got four or five statements correct; 27% got six or seven statements correct; and 12% got seven or more statements correct. The median score was 5.0.

[[26]]: Law Commission, Financial Remedies on Divorce and Dissolution: A Scoping Report, Law Com No 417 (2024).

[[27]]: R Mnookin and L Kornhauser, ‘Bargaining in the shadow of the law: The case of divorce’ (1979) 88 Yale LJ 950.

[[28]]: E Hitchings, ‘Official, operative and outsider justice: the ties that (may not) bind in family financial disputes’ (2017) 29(4) Child and Family Law Quarterly 359–378, at 378.