She Who Laughs Last? Pets, Perpetuities, and Other Problems with the Last Will and Testament of Taylor A. Swift.

Taylor Swift's 'Anti-Hero' may be the only pop song to feature a contentious probate dispute. This article considers the drafting problems of Taylor Swift's Will from the perspective of the law of England and Wales.

Taylor Swift’s ‘Anti-Hero’ is, to the best of my knowledge, the only pop song to feature a contentious probate dispute. (Reader: if you know another, do please tell.)

She sings:

‘I have this dream my daughter-in-law kills me for the money

She thinks I left them in the will

The family gathers ‘round and reads it and then someone screams out

"She’s laughing up at us from hell"‘

In three lines we get a murder, a will, and a family fallout. Good to know that the fever dreams of contentious probate lawyers and Taylor Swift are in such synchronicity.

The music video treats us to an interlude featuring a gloriously chaotic will-reading at the funeral of an elderly Taylor Swift. If you’ve not seen the video, please go and watch it here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b1kbLwvqugk (pick up from 2:12 if you want to skip to the funeral scene).

The proceedings descend into a fist fight between Taylor’s awful offspring – Preston, his wife Kimber, and Chad – when they discover what is in the Will. Chad, naturally, is recording it all for his Swift-themed podcast ‘Life Comes at You Swiftly’. Preston and Kimber remonstrate with Chad for trading off the Swift name. Chad accuses Kimber of murdering Taylor by pushing her off a balcony.

The text of the punch-up provoking Will reads:

‘Last Will and Testament of Taylor A. Swift

I bequeath the majority of my assets to the following:

Meredith Grey Swift,

Olivia Benson Swift,

Benjamin Button Swift.

The beach house will be converted into a cat sanctuary for the aforementioned.

And to my children, I leave 13 cents, each.’

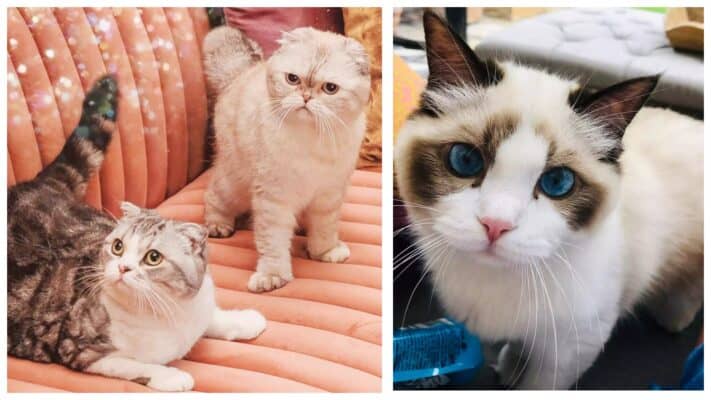

Meredith Grey, Olivia Benson and Benjamin Button are Taylor’s pet cats. Here they are:

From left to right: Meredith Grey Swift, Olivia Benson Swift, and Benjamin Button Swift

Chad suggests that his mother must have left a secret message in her Will that will reveal her children’s true inheritance. They read on to find a post-script:

‘P.S. There’s no secret encoded message that means something else. Love, Taylor.’

A young Taylor Swift then clambers out of the coffin, unnoticed by her brawling family.

All fun stuff, but for the probate practitioner the most remarkable feature of the scene is just how many problems Taylor Swift’s Will throws up – purpose trusts, perpetuities, certainty issues, implied revocation, a partial intestacy and more.

This is, of course, a fictitious scenario and it no doubt appears implausible that someone with the resources of Taylor Swift (estimated net worth $1.6 billion) with access to advisors and wealth managers would leave her personal affairs in such a pickle.

However, she would not be the only megastar to leave a muddle behind her. Prince died intestate leaving his $200 million estate to be shared amongst his sister and five half-siblings resulting in a six-year administration dispute which finally concluded in 2022. In 2014, a jury determined that Aretha Franklin’s estate passed under the terms of a handwritten note, ultimately deemed to be a valid holographic will under Michigan law, found beneath the cushions of her sofa and signed off with a smiley face drawn next to her name.

Below I work through the drafting problems in Taylor Swift’s Will from the perspective of the law of England and Wales. We don’t get to see the attestation clause, but let’s presume that the Will at least complies with the statutory formalities and consider its substantive content.

Sadly, my conclusion is that the undeserving Preston and Chad may yet have the last laugh.

TL;DR

For those short on time, attention span, or who (understandably) have limited enthusiasm for an exhaustive exploration of a fictional will, here is the summary:

The murder-for-inheritance dream sequence makes for a great pop video, but the drafting of Taylor Swift’s Will sets up a nightmarish probate problem and likely wholly fails to give effect to her wishes:

- A gift of ‘the majority of my assets’ to her three cats runs into four problems: (1) pets cannot be direct beneficiaries (so we are into strictly policed private purpose trusts), (2) the ‘majority’ of my assets is too vague to create a trust, (3) it likely breaches the rule against perpetual trusts (animal lives don’t count), and (4) there are no named trustees to carry out a trust of ‘imperfect obligation’ which depends on a willing trustee.

- The ‘beach house cat sanctuary’ is not charitable because it’s for her own pets and not wider animal welfare, so it fails for similar reasons.

- In the absence of an explicit revocation clause, we have confusion over whether the cat Will has revoked any prior will.

- With no effective residuary gift, the estate is poised for a partial intestacy – meaning, absent a residuary gift under an earlier will that survives, her children take under the intestacy rules. A nominal ‘13 cents, each’ does not prevent them from taking on intestacy without clear wording excluding them from all benefit from her estate.

- Whilst Kimber would be barred from benefiting if she killed Taylor (under the forfeiture rule), that wouldn’t stop Preston from inheriting unless he was complicit in Taylor’s death.

If you do choose to read on, treats await you such as judicial ponderings on the lifespans of butterflies, the will of the artist Turner, a story of an unsuccessful confidence trickster who attempted to marry for money, sensible suggestions as to how to provide for pets in wills, and my favourite real life example of capricious celebrity pet provision.

Issue 1: Can a testator leave ‘the majority’ of their assets to their pets?

There are four problems with this gift, which I unpack in more detail below:

- The gift is for the benefit of cats, not human beneficiaries.

- The subject matter of the gift ‘the majority of my assets’ is imprecise.

- The gift is of unlimited duration and we need to consider the ‘rule against perpetuities’.

- We have no named trustees.

1.1 The beneficiary principle

For a trust to be valid, there must be at least one identifiable person – the beneficiary – who has the right to enforce the trust’s terms – this, in summary, is the ‘beneficiary principle’. The leading case establishing this principle is Morice v Bishop of Durham (1804) 9 Ves Jr 399. The essential reasoning is that a trust creates obligations for trustees, and those obligations must correspond to rights that someone can enforce; otherwise, the trust cannot work in practice.

Beneficiaries can be individuals (natural persons) or other legal persons (such as companies). Cats are not recognised in English law as having legal personality – cats cannot own property or bequeath it by will, enter into contracts, or sue or be sued. For this reason, the attempted gift of property to Meredith, Olivia and Benjamin is ineffective as a direct gift and would be best analysed as an attempt to create a purpose trust for the maintenance of the cats.

Charitable trusts created for a purpose that is for public benefit are an exception to the beneficiary principle. They do not require a specific beneficiary because the Attorney General, acting for the public interest, is responsible for enforcement. Private purpose trusts – those set up for a purpose rather than particular people, and which are not charitable – generally fail due to the absence of an ascertainable beneficiary.

However, during the 150 years or so following Morice v Bishop of Durham, a handful of exceptions to the beneficiary principle sprang up in the form of private purpose trusts that the courts permitted to stand. These exceptional purposes include erecting and maintaining graves and monuments and saying private masses for the dead. Relevantly for Taylor Swift’s Will, gifts for the maintenance of particular animals are also recognised as permitted trusts for purposes, as in Pettingall v Pettingall (1842) 11 LJ Ch 176 (gift of £50 per year for the upkeep of the testator’s favourite black mare) and Re Dean (1889) 41 Ch.D. 552 (gift of £750 per annum for the maintenance of the testator’s horses and dogs).

It is fair to say that, whilst these permitted exceptions to the rule against private purpose trusts still survive, they are not enthusiastically embraced by the courts.

The exceptions were described as ‘concessions to human weakness or sentiment’ by Roxburgh J in Re Astor’s Settlement [1952] Ch 534. Harman LJ described these cases in Re Endacott [1960] Ch 232 as ‘troublesome, anomalous and aberrant’ and as perhaps being ‘occasions when Homer has nodded’ and which ought to be overruled (although they have not been). He emphasised that the exceptions ‘ought not to be increased in number, nor indeed followed, except where the one is exactly like another’.

The result is that these exceptions allow certain private purpose trusts to exist without a named beneficiary, but only in narrowly defined situations that are policed strictly and which are unlikely to be extended. Therefore, although a gift designated for the upkeep of the cats is permissible in principle, it is likely that a court would adopt a relatively stringent approach when reviewing such a provision.

1.2 Certainty of subject matter

As every student of equity and trusts knows, to create a valid express trust, the settlor must comply with the three certainties, namely:

- Certainty of intention to create a trust;

- Certainty of the subject matter (property) of the trust;

- Certainty of objects (the beneficiaries or purposes of the trust).

A gift or trust will fail if the subject matter — the property being given — is not defined with sufficient clarity. The law requires that the property be either clearly identified or objectively ascertainable. Two well-known cases illustrate this point:

- In Palmer v Simmonds (1854) 2 Drew 221, the phrase ‘the bulk of my residuary estate’ was held to be too uncertain to form the subject matter of a trust, as it was not clear what property was intended.

- In Sprange v Barnard (1789) 2 Bro CC 585, an attempted bequest of ‘the remaining part of what is left that he does not want for his own wants and use’ was found to lack certainty of subject matter and therefore failed as a trust.

The word ‘majority’ in Taylor Swift’s Will suffers from the same defect as ‘bulk’ in Palmer. ‘Majority’ is not a fixed quantum; it simply means ‘more than half’. That raises two problems: (i) more than half of what (each individual asset, or a share of the estate by value?) and (ii) how is the precise quantum to be determined?

It might be argued that when read with the only other provisions, and assuming that Taylor intended her Will to dispose of all of her assets, the ‘majority of my assets’ was intended to operate as a sweep-up of everything except the 26¢ and the beach house.

However, even if the court was minded to adopt such an interpretation, for reasons explained further below, the clause is not successful as a residuary gift, and the clause also collides with the perpetuity rules.

1.3 Perpetuity issues

Non-charitable purpose trusts, including trusts for the maintenance of pets, must comply with the common law perpetuity rules and specifically the rule against ‘inalienability’ or ‘perpetual trusts’.

The purpose of the rule against perpetual trusts is to keep property from being controlled indefinitely by the whims of someone who has long since passed away. In simple terms, the rule states that property interests must vest (become absolutely owned) within a certain time frame.

A non-charitable purpose trust is void if it can last longer than the permitted perpetuity period. It is important to note that, in the case of private purpose trusts, it must be possible to tell from the outset that some person or persons will become absolutely entitled to the trust property by the end of the permissible period.[1]

Under the common law rule, a private purpose trust must not exceed the period of a ‘life in being’ (or lives in being) plus 21 years. This means that the terms of the will or trust must specifically provide for the purpose trust to come to an end within the period of 21 years from the death of the specified measuring life. If no life in being is specified, the duration of the trust must be restricted to 21 years. Formulations such as ‘so long as the law permits’ are also acceptable and imply a period of 21 years.[2]

More than one life can be specified so long as the lives in being are not so numerous as to be unworkable.[3] The measuring lives can include a child ‘en ventre sa mere’ and do not need to have any interest in the property itself or even be known to the testator – royal lives are commonly selected as royal deaths are well documented and members of the royal family are generally long-lived.

Most practitioner and academic commentary is in agreement that perpetuity periods, under the common law rule, must be measured by reference to human lives and that animals cannot themselves be ‘lives in being’.[4] There are a handful of cases in which the courts seem to have taken a contrary view:

- In Re Dean, North J noted that a testator must be careful to ensure that the trust comes to an end within the limits fixed by the rule against perpetuities, otherwise the trust would be void. However, he then failed to go on to address whether the trust, which provided for the upkeep of the testator’s horses and hounds for 50 years were they to live that long (not a valid perpetuity period under the common law principles), actually complied with the rule.

- In Re Haines, Johnson v Haines (1952) Times, 7 November 1952, ‘judicial notice’ was taken of the fact that the average life expectancy of a cat was less than 21 years and an unlimited trust for the upkeep of the testator’s cats was upheld on the basis that it was assumed that the cats would die, and thus the purpose would end, within the permitted perpetuity period.

The better view is that expressed in the Irish case of Re Kelly [1932] IR 255, where the court observed, in poetic terms, as follows:

If the lives of the dogs or other animals could be taken into account in reckoning the maximum period of ‘lives in being and twenty-one years afterwards’ any contingent or executory interest might be properly limited, so as only to vest within the lives of specified carp, or tortoises, or other animals that might live for over a hundred years, and for twenty-one years afterwards, which, of course, is absurd. ‘Lives’ means human lives. It was suggested that the last of the dogs could in fact not outlive the testator by more than twenty-one years. I know nothing of that. The Court does not enter into the question of a dog’s expectation of life. In point of fact neighbour’s dogs and cats are unpleasantly long-lived; but I have no knowledge of their precise expectation of life. Anyway the maximum period is exceeded by the lives even of specified butterflies and twenty-one years afterwards. And even, according to my decision—and, I confess, it displays this weakness on being pressed to a logical conclusion—the expiration of the life of a single butterfly, even without the twenty-one years, would be too remote, despite all the world of poetry that may be thereby destroyed. In Robinson v Hardcastle, Lord Thurlow defined a perpetuity in these words: ‘What is a perpetuity, but the extending the estate beyond a life in being, and twenty-one years after?’ Of course by ‘a life’ he means lives; and there can be no doubt that ‘lives’ means lives of human beings, not of animals or trees in California.

In summary on the authority of Re Kelly: animals do not count as lives in being and the lives of even the most short-lived of creatures, such as butterflies, will be presumed to exceed the permitted perpetuity period.

On the particular facts of Re Kelly, the testator gave £100 to his trustees for the purpose of spending £4 on the support of each of his four dogs per year. The court refused to read into the will an implied limitation of the trust to a period of 21 years but felt able to treat the gift as a series of severable payments, each to last for a period of a year, the first 21 of which were valid.

Here, the gift for Meredith, Olivia and Benjamin in Taylor Swift’s Will is of unlimited duration. No period at all is specified – there is no saving provision such as ‘as long as the law allows’, the gift is not even tied to the lives of the cats, and the gift is not severable into instalments that might be saved by the reasoning in Re Kelly. It is likely that the gift is void for infringing the rule against perpetuities on the basis that no valid perpetuity period has been specified and animal lives do not count as lives in being. At best, it would last for a maximum of 21 years, or until the cats died (if earlier).

1.4 Lack of named trustees

As we have established above, the cats themselves cannot hold any property. Taylor has not named any trustees in her Will. This would not be an issue that defeats a valid trust of perfect obligation (whether for persons or for charitable purposes) as it is a maxim of equity that ‘equity will not allow a trust to fail for want of a trustee’ and, in extremis, where there is no one else willing or capable of acting, the court can appoint the Public Trustee to act as a trustee of last resort.

The case of Trimmer v Danby (1856) 25 LJ Ch 424 concerned the will of artist JMW Turner, who directed his executors to use a sum of money to build a monument to him in St Paul’s Cathedral ‘among those of my brothers in art’. Although Turner’s executors were willing to carry out Turner’s wishes, Kindersley V-C observed:

‘I do not suppose that there would be anyone who could compel the executors to carry out this bequest and raise the monument; but if ... the trustees insist upon the trust being executed, my opinion is that this Court is bound to see it is carried out.’

This statement underscores the peculiar nature of private purpose trusts: they are trusts of ‘imperfect obligation’, lacking an identifiable beneficiary to enforce them. Their effectiveness depends on the presence of a willing trustee, as the court is unlikely to compel performance where the trustees do not wish to act.

It is unclear whether the principle that ‘equity will not allow a trust to fail for want of a trustee’ applies to private purpose trusts. It certainly seems unlikely that the Public Trustee would act in the absence of any other willing trustee. If there is some other fit and proper person willing to carry out a purpose trust that is otherwise valid and complies with the perpetuities rule, it is possible that the court would use its powers to replace an unwilling trustee. If no one is willing to act as trustee, it is likely that the attempted gift to the cats would fail.

Could one of Taylor’s sons, or Kimber, put themselves forward as a willing trustee in order to seize control of the assets for their own benefit? This would not be a successful strategy, as the Court, if satisfied that the trust is enforceable, would be alive to the possibility of abuse. In the unlikely event that the gift is valid, the court would make what is sometimes referred to as a ‘Pettingall order’ requiring any trustee to give an undertaking to use the assets solely for the purpose permitted by the Will, and giving permission to the parties entitled to the property if the trust fails to make an application to the Court if the funds are not used for the permitted purposes.[5]

Conclusions on Issue 1

Meredith, Olivia and Benjamin may have been ‘cats that got the cream’ in Taylor’s lifetime but it seems that those days are at an end. Overall, given the general deprecation of private purpose trusts, it is unlikely that a court would strive to save a gift that suffers from quite so many deficiencies and that would have the effect, if upheld in the terms drafted, of tying up a vast estate out of all proportions to the needs of even the most pampered of pussycats for perhaps as long as 21 years depending on the lifespans of the cats. Most likely, the gift of the ‘majority of my assets’ to the cats will fail.

Issue 2: Can beach houses be dedicated to a private cat sanctuary for three spoilt kitties?

Trusts for the welfare of animals generally are charitable.[6] Trusts for the benefit of your pets alone, are not.

If Taylor had provided that the beach house should be dedicated to being a cat sanctuary generally, this would be a permissible charitable trust. If for any reason the use of the property as a cat sanctuary was not practical, a ‘cy-près scheme’ (deriving from old French, meaning ‘near to’) can be established allowing the property to be applied to other related purposes or charities taking into account the spirit of the original gift. Charitable trusts can last for ever and do not need to comply with the perpetuity rules.

However, Taylor Swift’s Will limits the use of the beach house as a cat sanctuary to Meredith, Olivia and Benjamin (‘a cat sanctuary for the aforementioned’), rather than cats generally, and this provision will not be interpreted as being charitable.

This is a further attempt to create a trust for private purposes and again, this raises the same problems with the perpetuity rule as above and would likely be void for failing to specify a valid perpetuity period.

It is worth observing that I have not found any successful example of a testator creating a trust dedicating the use of a property for their pets – the testator in Re Kelly including a direction in his will that the dogs should be ‘kept in the old house at Upper Tullaroan’ but the court was not asked to rule on this provision. All of the successful cases that I have come across involve the dedication of relatively modest sums of money to the ongoing maintenance costs of the testator’s animals. It appears to me that a provision of this description, even if it did not suffer from perpetuity problems, likely goes further than the existing cases. Following Re Endacott, it is unlikely that a court would be willing to endorse an extension to the recognised category of trusts for the maintenance of individual animals.

Sorry kitties, no beach house for you. Although, as Kimber observes in the fight scene ‘cats don’t even like the beach’.

Issue 3: Lack of a residuary gift – what happens if you fail to make gifts of all your assets?

A residuary gift is one that is intended to pass everything that remains after all debts, taxes, and specific gifts have been paid or distributed. It is a ‘catch-all’ provision that ensures nothing is left undisposed of, including sweeping up any gifts that fail.

Many phrases can amount to a valid residuary gift if they clearly indicate an intention to include everything not otherwise given away. Usually, if drafted by a lawyer, the gift of residue will expressly refer to the ‘residue’ or ‘remainder’ or property ‘not otherwise disposed of’ or wording to similar effect. Wording such as ‘what shall be left’,[7] ‘all I am worth’,[8] ‘balance’,[9] or ‘surplus’[10] will usually be sufficient descriptors of a gift of residue.

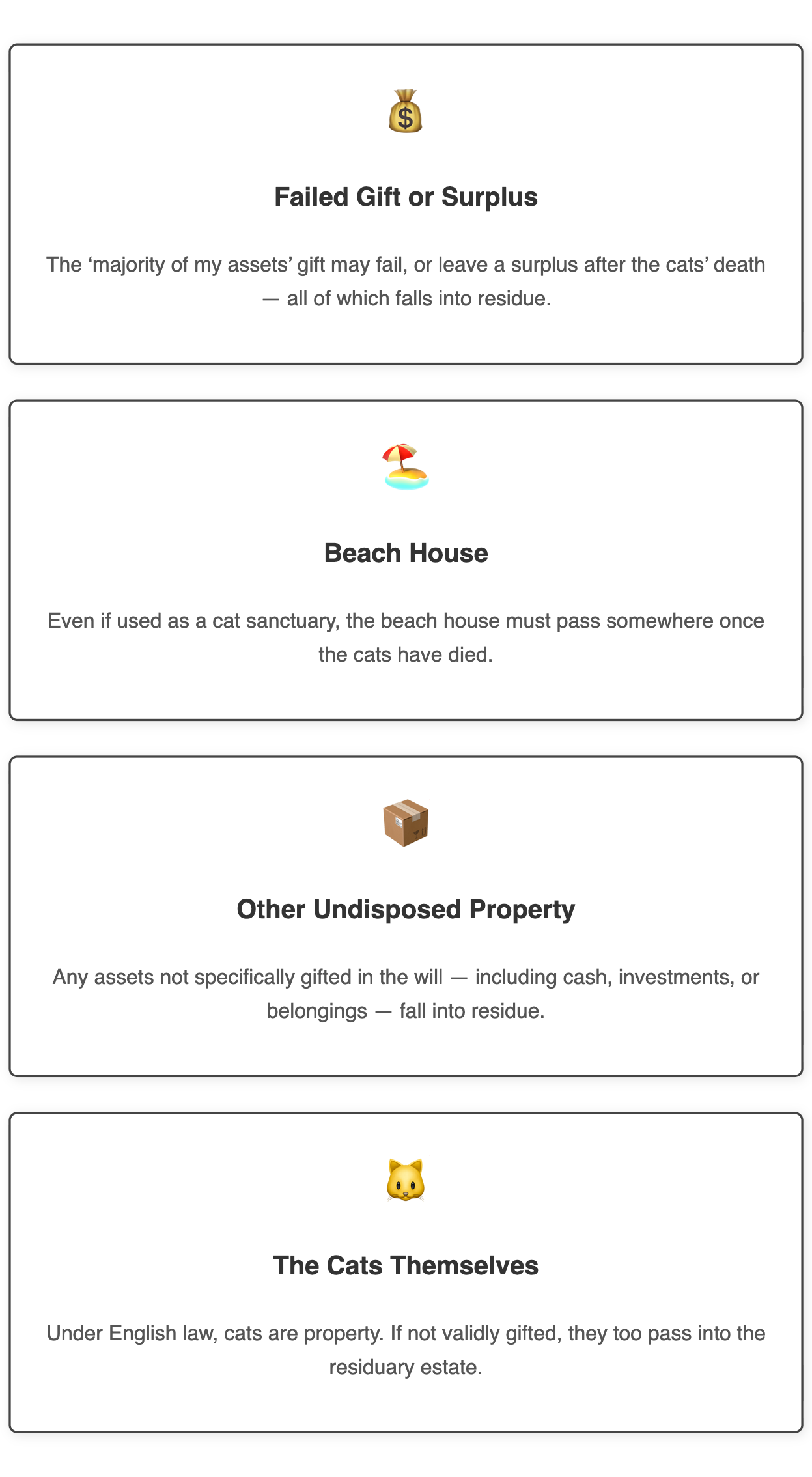

The phrase ‘the majority of my assets’ in Taylor Swift’s Will is not equivalent to a gift of the residue on our facts, even if it could be construed as an attempt to give everything to the cats except for the 13¢ each and the beach house. This is because the following elements will all fall into residue as they cannot be irrevocably appointed to the cats in perpetuity and must pass somewhere:

If the attempted gifts to the cats fail, Taylor’s entire estate save for the 13¢ each to Preston and Chad will fall into residue. Unless there is an earlier will with a valid gift of residue that the court considers survives the later will, the result will be a partial intestacy – so let us consider next whether any earlier Will has been revoked and the outcome if there is an intestacy of the residue.

Issue 4: No revocation clause – which will prevails?

Under s. 20 of the Wills Act 1837 the whole or any part of a will or codicil may be revoked by another duly executed will or codicil. This is not the only way that a will can be revoked – under English law a will can be revoked by destruction or obliteration and (subject to the possibility of reform) a will may also be revoked automatically by marrying or forming a civil partnership.

For a previous will to be revoked by a later will, the later document must either clearly state that it revokes the former, or the terms of the two documents must be so inconsistent that they cannot reasonably operate together. Simply making a new will or testamentary document does not automatically revoke an earlier one.

Taylor Swift’s Will from the funeral scene contains no express revocation clause. We do not know whether she made an earlier will or, if she did, what its terms were. If she has made an earlier will, then, assuming that it was not revoked by any other act, the question would arise as to whether it was revoked wholly or in part by the most recent Will. Without reviewing the terms of any earlier will, we are limited in how far we can speculate, but a few observations may be made as to the approach to be taken:

- Presumption against revocation: The question of whether a prior will or codicil has been impliedly revoked by a later will is one of the construction (interpretation) of the will. There is a presumption against implied revocation; an implied revocation will only be found if there is a logical inconsistency between the provisions of the two wills.

- Presumption against intestacy: In parallel, the courts apply a presumption against intestacy when interpreting a will.[11] Where two possible interpretations of a will are open, the court will generally favour the construction that avoids a total or partial intestacy, on the basis that it is unlikely a testator would deliberately omit to dispose of their property. This presumption does not override clear words or demonstrable intention, but it may assist in resolving ambiguity or doubt as to whether an earlier will was intended to remain operative.

- ’Last Will’ – Taylor’s Will is described as her last Will and testament. However, this does not, by itself, count as an express revocation of any previous wills.[12] In fact, any number of testamentary documents, regardless of when they were made, can be admitted to probate as collectively constituting the deceased’s final wishes, provided it is clear they were intended as such and they can stand together without contradiction.

- Revocation by inconsistency: Revocation by inconsistency can apply to the entirety of the prior will if the documents are wholly contradictory, or it can be partial if only certain provisions are inconsistent. The essential consideration is to establish which dispositions the testator intended to revoke or to retain.[13] If the new will was intended to be a complete scheme of distribution, the earlier will may be wholly revoked even if the later will fails to include a gift of residue.[14] Where the only indication of revocation is an inconsistent gift in a later will and that gift proves to be invalid, the gift in the earlier will is not revoked – but this is a question of intention and if there is a clear intention to revoke the earlier instrument the failure of the second gift will not restore the first one.[15]

- Ambiguity and admissibility of ‘extrinsic evidence’: As explained by the Supreme Court in Marley v Rawlings [2014] UKSC 2, the court seeks to interpret a will so as to find the testator’s intended meaning in a manner akin to a contract, by identifying the meaning of the relevant words, (a) in the light of (i) the natural and ordinary meaning of those words, (ii) the overall purpose of the document, (iii) any other provisions of the document, (iv) the facts known or assumed by the testator at the time that the document was executed (so-called ‘armchair’ evidence, the court seeking to place itself in the testator’s armchair), and (v) common sense, but (b) ignoring subjective evidence of any party’s intentions. Where any part of the will is meaningless, ambiguous on its face, or ambiguous in the light of evidence as to the surrounding circumstances (other than evidence of the testator’s intention), the court may then admit evidence of the testator’s actual intentions (such as any instructions given by the testator to a will drafter or anything that the testator said about the will) so as to assist in the interpretation of the will, under s 21 of the Administration of Justice Act 1982.

- Rectification: It is also worth noting that s. 20 of the Administration of Justice Act 1982 enables the court to rectify (redraft, in essence) a will that ‘is so expressed that it fails to carry out the testator’s intentions, in consequence (a) of a clerical error; or (b) of a failure to understand his instructions’. This provision could be used to correct a drafting error, if the testator intended to revoke their earlier will – a clerical error can be made by a testator in writing out a homemade will.[16] S. 20 AJA 1982 does not allow the courts to rectify a will where the draftsman understood their instructions and applied their mind to drafting the relevant provision but the words used failed to achieve the testator’s intentions.[17]

In summary, absent an express revocation clause, revocation by implication turns wholly on intention and the objective is to establish not which will the testator intended to be admitted to probate but which provisions.

The ultimate outcome here would depend on the degree of inconsistency between the two instruments and the strength of the evidence of intention. Subject to that caveat, there is a respectable argument here that, despite the fact that Taylor Swift’s Will contains no valid residuary gift and despite the likely failure of the gifts to the cats, the Will nonetheless has by implication revoked any prior will – particularly if the earlier will left her residuary estate to Chad and Preston.

Notwithstanding the fact that the drafting of Taylor Swift’s Will is ineffective in disposing of the entirety of her estate, it seems to have been intended to be a complete scheme of distribution, as conceived by a lay testator who has not thought through the consequences of the gifts to the cats failing. It seems likely that the gift of the ‘majority’ of her assets plus the beach house was an attempt to divert her entire estate bar the nominal 26¢ to her cats. The postscript – ‘There’s no secret encoded message that means something else’ – also supports the view that Taylor regarded this Will as the definitive expression of her testamentary intentions, excluding any external or prior arrangements.

It does not seem likely that Taylor would have intended Chad and Preston to take their 13¢ each plus any more generous provision under an earlier will. Taylor Swift’s Will appears to have been made with the motivation of wholly disinheriting Chad and Preston, save for a nominal ‘spite’ gift of 13¢ each – that is an intention that is apparent from the face of the Will as there is no other logical explanation for such a wealthy testatrix to make a nominal gift other than to mark her displeasure with her children.

The position might be different if any earlier will leaves residue to other beneficiaries, in which instance it may be concluded that Taylor intended to revoke any more generous gifts to her children in the earlier will and substitute them for the token 13¢ gift but that she intended to leave intact the earlier gift of residue (applying the presumption against intestacy) in the absence of any specific evidence that she intended to revoke the residuary gift under the earlier will.

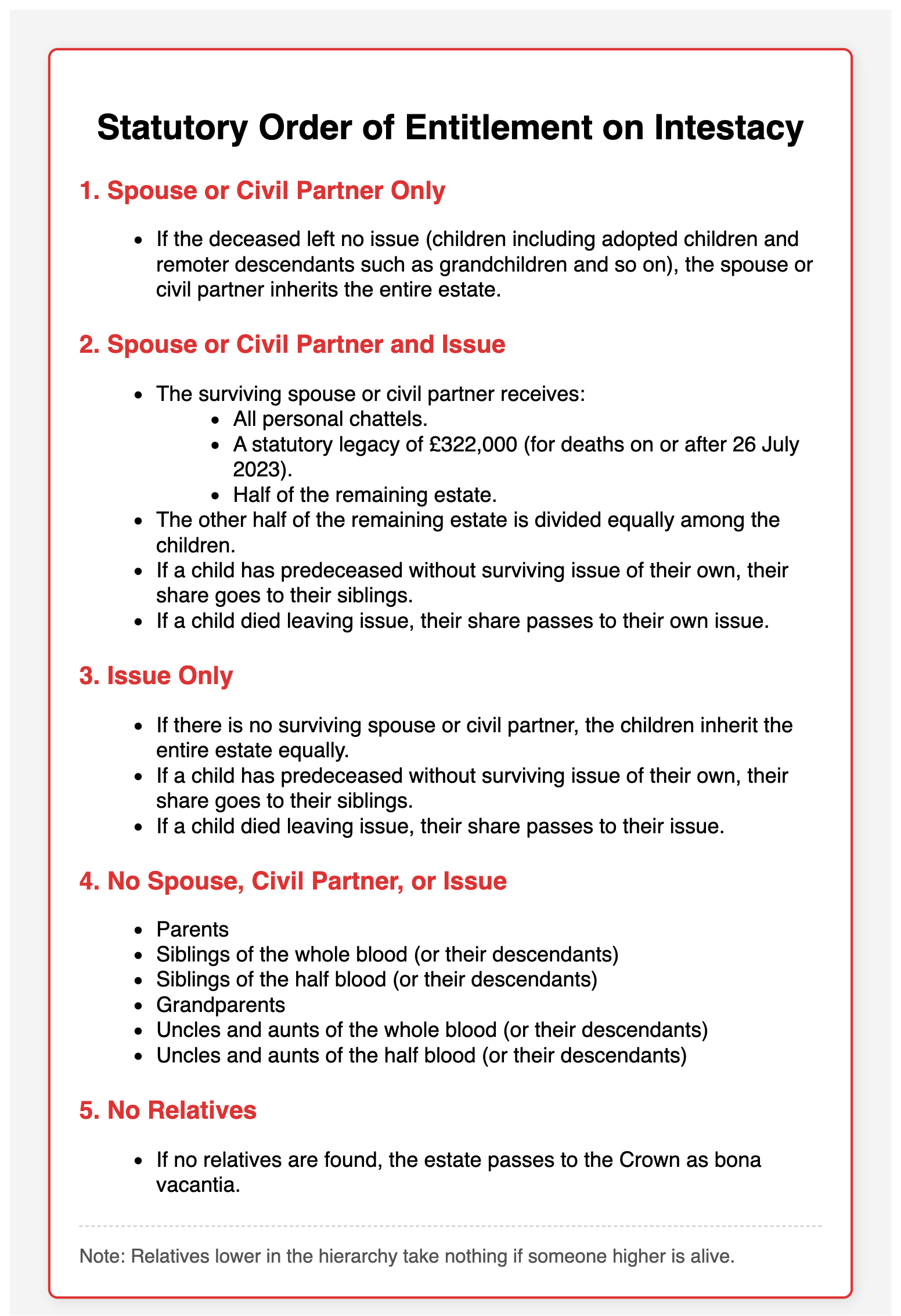

Issue 5: Intestacy Rules O.K.

Assuming that there is no earlier will, or it has been wholly revoked by the most recent Will, the result will be a partial intestacy. In England and Wales, when a person dies without a valid will or with a valid will but there is some undisposed of residue, their estate (or the undisposed of portion) is distributed according to the intestacy rules set out in the Administration of Estates Act 1925, ss 46–47. These rules determine who inherits based on their relationship to the deceased. Relatives ranking further down the statutory order of priority take nothing where there are surviving beneficiaries in a higher priority class.

As we have established, the attempted gifts to the cats are likely wholly invalid and there is an intestacy of the entire estate bar the nominal legacies to Chad and Preston. Assuming that Taylor was unmarried at the date of her death, Preston and Chad ordinarily would stand to inherit the undisposed of residue of her estate under the intestacy rules.

However, a testator may specify in their will that one or more relatives – who would otherwise inherit under intestacy laws – are to receive no portion of the estate. Such a direction is regarded as an implied gift to those individuals who would be entitled under the intestacy rules in the absence of the excluded parties. The effect is to treat the excluded parties as if they had died before the testator. However, a testator cannot completely exclude all next of kin so as to create an implied gift in favour of the Crown.[18] A gift by implication only arises where the testator’s intention is clear from the face of the will, but there is a gap to be filled in to give effect to that intention.[19]

Assuming that the elderly Taylor is survived by other relatives, possibly grandchildren by Chad and Preston who would take if their parents are treated as having died before Taylor, or her brother Austin, who would take if she died without a spouse or issue or surviving parents, can those relatives argue that Preston and Chad have by implication been excluded from benefiting from Taylor’s residuary gift by the nominal 13¢ legacies?

The following cases illustrate the court’s approach to implied gifts by exclusion:

-

In Vachell v Breton (1706) 5 Bro Parl Cas 5, the testator specifically bequeathed ‘ten shillings each and no more’ to two of his children. The inclusion of the phrase ‘no more’ was pivotal – the House of Lords determined that these words were sufficient to exclude the children from receiving any further share of the estate under intestacy.

-

In Ramsay v Shelmerdine (1865) 1 Eq. 129 the testator had made a codicil revoking all provision in his will in favour of his daughter Ellen, with the result that an intestacy arose as to Ellen’s share. The court distinguished Vachell. Ellen was still entitled to a share on intestacy as the testator had not explicitly used wording that explicitly excluded her from all benefit from his estate (merely from benefiting under his will).

-

Re Wynn [1983] 3 All ER 310 is a more modern example. In this case the testatrix was a wealthy woman who had at the age of 73 married Mr Wynn, who was 48 at the time. Mr Wynn was alleged to be a confidence trickster who had married the testatrix for her money and the allegations had led to criminal proceedings being brought against him in Switzerland which were dropped when she died. She had made a will that read ‘I, Olga Wynn, revoke all previous wills today … I hereby wish that all I possess is not given to my husband Anthony Wynn’. She had made the will in response to a request from Mr Wynn himself that she should produce a document that demonstrated that he would not benefit from her money. In a move that is difficult to see as anything less than a show of true colours, Mr Wynn sought to argue that he was nonetheless entitled to her estate on intestacy. The court concluded that the wording of the will had the effect of excluding Mr Wynn from all benefit and that this must mean excluding him from benefiting on intestacy in circumstances where intestacy was the inevitable effect of the will. The entire estate therefore passed to the children of the testatrix.

For a person to be implicitly cut out of the intestacy queue, the wording of the will needs to clearly express the intention that they are to take no benefit at all from the testator’s estate (and not just no benefit under their will). Taylor’s ‘13 cents, each’ is merely a nominal legacy and contains no exclusionary wording (such as ‘and no more’). On the authorities just reviewed, that is insufficient to disinherit the children on intestacy.

It seems unlikely that any other relatives could argue for Taylor Swift’s Will to be construed or rectified so as to explicitly exclude Preston and Chad in favour of more remote relatives because (absent clear evidence to the contrary) it seems that Taylor’s intention was to disinherit Preston and Chad in favour of her beloved cats, rather than to benefit more remote relatives over her children – for all we know, relations with her wider family were even frostier.

With the pet provisions likely failing and no effective residuary gift, the undisposed residue therefore devolves as on intestacy and – assuming Taylor was unmarried – passes in its entirety to Preston and Chad, notwithstanding the 13¢ gifts.

Issue 6: No Named Executors — entitlement to a grant of probate

Taylor has not nominated any executors, responsible for implementing her wishes. With no executor named, probate of Taylor Swift’s Will will be granted to an administrator as a grant of ‘letters of administration with the will annexed’.

Entitlement to the grant is governed by r.20 Non-Contentious Probate Rules 1987, which sets out an order of priority in terms of who is entitled to take a grant, as follows in descending order:

-

The Executor: The person appointed in the will to carry out its instructions.

-

Residuary Legatee or Devisee holding in trust: A person who receives the remainder of the estate after any gifts of specific property, but holds it for another person.

-

Other Residuary Legatee or Devisee: Any other person entitled to the rest of the estate, or who receives the undisposed-of part (or, if they have already died, that person’s personal representative).

-

Others With an Interest in the Estate: Legatees, devisees or creditors – so someone who receives a specific gift under the will or to whom the deceased owed money.

Given our conclusions above, Preston and Chad, subject to the court’s discretionary powers to ‘pass over’ either of them in the case of a dispute,[20] will be entitled to take out letters of administration of Taylor Swift’s Will enabling them to administer the estate and to decide what becomes of Meredith, Olivia and Benjamin.

Issue 7: 1975 Act claims – could Preston and Chad claim against Taylor’s estate if they receive no more than 13¢?

In the event that they receive nothing more than 13¢ and the residue of the estate passes elsewhere, Taylor’s children they would have standing to bring claims under the Inheritance (Provision for Family and Dependants) Act 1975. The key question would be whether Taylor Swift’s Will fails to make reasonable financial provision for Preston and Chad, assessed by reference to the factors set out under s.3 of the 1975 Act, including their financial needs and resources, any obligations Taylor owed to them, the size of the net estate, and any other matter including the conduct of Preston and Chad, or any other person, which the court considers relevant.

The question of whether reasonable financial provision has been made for an adult child is assessed by reference to the ‘maintenance’ standard, which means provision to discharge the costs of daily living at the standard appropriate to their station in life. However, adult children who are capable of living independently will generally struggle to succeed unless there is a compelling moral claim—something more than financial need plus the necessary parent-child relationship will be required to found a claim, as emphasised by Lord Hughes in Ilott v The Blue Cross [2017] UKSC 17. In the absence of evidence of real financial needs (as opposed to wants) combined with dependency, disability, or an unmet moral claim, a 1975 Act claim by Preston or Chad would likely be unsuccessful.

Issue 8: Forfeiture – ‘my daughter-in-law kills me for the money’ – Preston’s position

The forfeiture rule is a longstanding principle of public policy which precludes a person who has unlawfully killed another from acquiring a benefit as a consequence of the killing. This principle was first established in the case law, as reflected in Cleaver v Mutual Reserve Fund Life Association [1892] 1 QB 147, where it was held that a murderer cannot benefit from the estate or life insurance policy of their victim.

s.1 of the Forfeiture Act 1982 codifies the rule, defining it as a rule of public policy precluding a person who has unlawfully killed another from acquiring a benefit in consequence of the killing. This includes aiding, abetting, counselling, or procuring the death.[21] The Act gives the court discretion (except in cases of murder) to modify or exclude the operation of the rule if, considering all the circumstances, justice so requires.[22] Under the Estates of Deceased Persons (Forfeiture Rule and Law of Succession) Act 2011, a person who forfeits is treated as having predeceased for succession purposes.

If Kimber was a beneficiary and murdered Taylor, she would be barred from benefiting from her estate under both the common law rule (as in Cleaver) and the statutory regime under the Forfeiture Act 1982.

However, Preston’s entitlement is independent of Kimber. The forfeiture rule does not disqualify a spouse of the killer unless they were a party to the killing or are claiming through the killer’s disqualified title (i.e. as a beneficiary of the killer’s estate). So Preston would benefit under Taylor Swift’s Will and on intestacy, unless he was complicit in the killing.

Takeaways

Primarily this post is simply an itch that needed scratching, but let’s see if we can identify some learning points of wider application from our exploration of Taylor Swift’s Will.

Perils of home-drafted wills: In the (perhaps unlikely) event that any lay reader has persisted this far, the main messages are that poor drafting can entirely defeat your testamentary wishes and that a short homemade will of less than 50 words in length can bequeath your intended heirs a conundrum of enormous complexity. The money saved on having a professional draw up your will, may be spent several times over if it is necessary to instruct a member of the Chancery Bar to unravel the ramifications of your expressed wishes or to apply to court for a determination. In particular, advice should be taken if your wishes are likely to be controversial or have any element of complexity to them. If determined to make your own will, at least use a standard DIY template that contains a properly drafted residuary clause and express revocation clause.

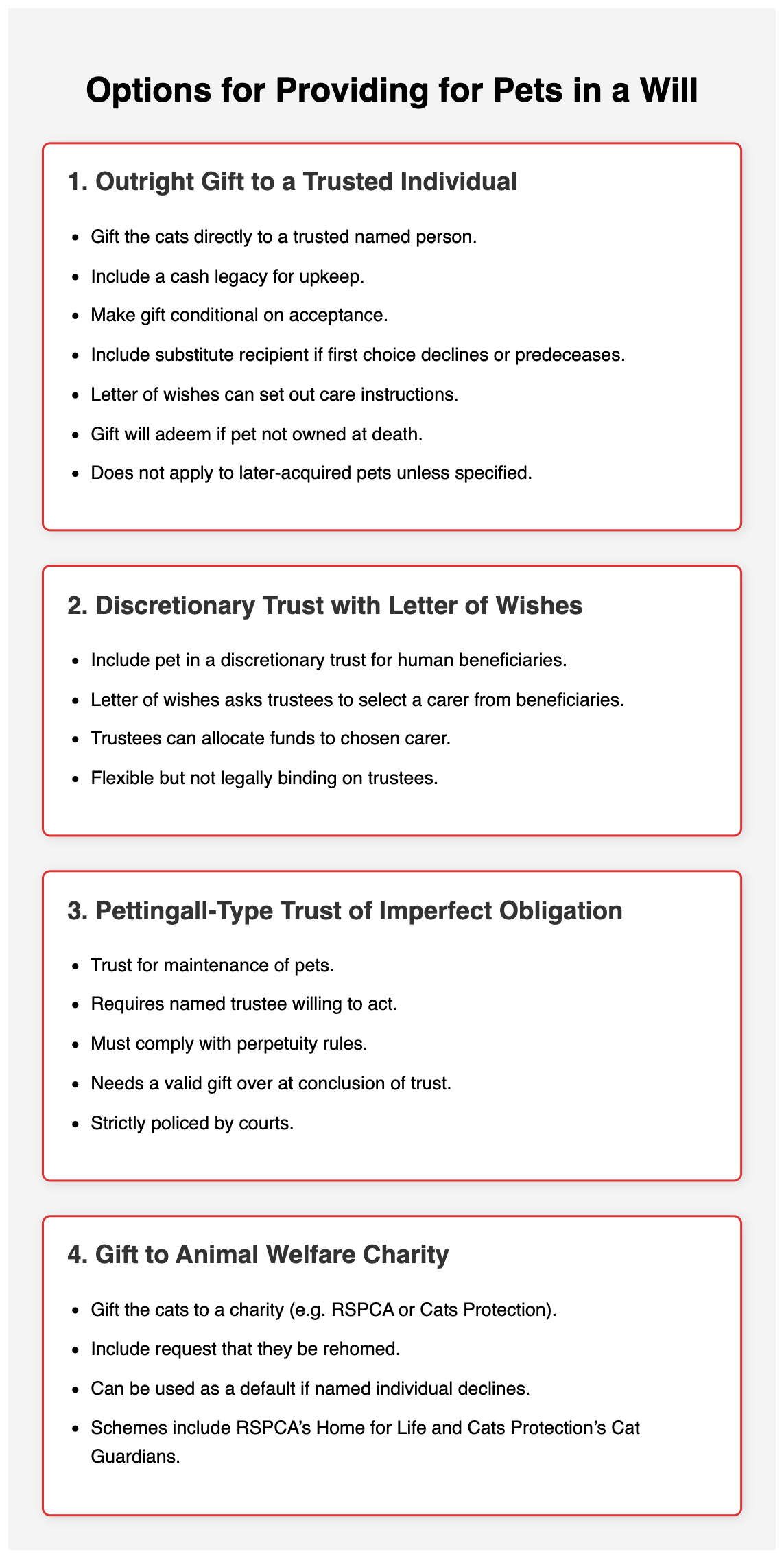

Provision for pets: If Taylor’s goal was to ensure Meredith, Olivia and Benjamin were cared for after her death, there were several well-established options available to her, which a testator seeking to provide for their pets could adopt:

Finally, I promised a further example of celebrities making extravagant provision for her pets. There are many such stories, but my personal favourite concerns Dusty Springfield, whose will provided for a portion of her estate to be used for the care of her cat, Nicholas, on her death in 1999. Her accompanying requests reportedly included that Nicholas:

- Be fed baby food imported to Britain from the United States.

- Live in a 7-foot indoor tree house.

- Be serenaded to sleep each night by a stereo system playing Dusty’s hits.

- Have his bed lined with Dusty’s pillowcase and nightgown.

- Be ‘married’ to the female cat of his appointed guardian.

Dusty and cat c. 1963 (probably not Nicholas)

The Perpetuities and Accumulations Act 2009 does not rescue this: it modernises the remoteness of vesting rules and default periods for trusts for persons, but it does not validate or relax the perpetuity rules for private purpose trusts: see s. 18. ↩︎

Re Hooper [1932] 1 Ch 38 (Ch); Pirbright v Salwey [1896] WN 86. ↩︎

E.g. Re Moore [1901] 1 Ch 936 where a gift was held void where vesting was postponed ‘for the longest period allowed by law, that is to say, until the period of 21 years from the death of the last survivor of all persons who shall be living at my death’. ↩︎

See e.g. Lewin on Trusts 20th Ed. at 6-061 and Theobald on Wills 19th Ed. at 10-026. See further Morris, Alec, ‘Private Purpose Trusts and the Re Denley Trust 50 Years On’ (October 26, 2020) (2020) 34(3) Trust Law International 165 – where Re Dean and Re Haines are described on the perpetuity point as ‘not so much “occasions when Homer has nodded” but rather occasions for which he was comatose’. For a contrary view, see Wilde, D. (2021) ‘The rule against perpetual trusts: part 1 – trusts for non-charitable purposes.’ Trust Law International, 35 (3). pp 149–159. ↩︎

Named after the case of Pettingall v Pettingall, followed in Re Thompson [1934] Ch. 342. ↩︎

See for example Re Moss [1949] 1 All ER 495 (trust to benefit cats and kittens needing care and attention held to be charitable). ↩︎

Duhamel v Ardovin (1751) 2 Ves Sen 162, Leighton v Bailie (1834) 3 My & K 267 (‘I think there will be something left to give to A’). ↩︎

Huxtep v Brooman (1785) 1 Bro C C 437. ↩︎

Re Biden (1906) 4 WLR 477. ↩︎

Lockhart v Ray (1880) 20 NBR 129. ↩︎

Re Harrison (1885) 30 Ch.D. 390. ↩︎

See e.g. Cutto v Gilbert (1854) 9 Moo.P.C. 131; Stoddart v Grant (1852) 1 Macq. 171; Freeman v Freeman (1854) Kay 479; 5 D.M. & G. 704; Lemage v Goodban (1865) 1 P. & D. 57. ↩︎

Lemage v Goodban (1865) LR 1 P & D 57. ↩︎

This was the conclusion in Dempsey v Lawson (1877) 2 P.D. 98 where the testatrix’s later homemade will had changed the identity of some beneficiaries, substantially altering the shares of others, and had expressly dealt with her most valuable assets consisting of stocks and shares but did not include a gift of residue. The court considered it most likely that the testatrix did not include a gift of residue because she had thought that she had disposed of everything and it did not deem it necessary to include one. The conclusion was that the earlier will was revoked entirely and the undisposed of cash passed under the intestacy rules, instead of under the residuary gift in the earlier will. Cf. Perdoni v Curati [2012] EWCA Civ 1381 where a later will named the wife as the heir of the testator’s Italian estate but contained no revocation clause and said nothing about the contingency of her predeceasing the testator, whereas his earlier English will had left the testator’s estate to his wife with a substitute gift for the wife’s niece and nephew if she died before him. The Court of Appeal held that the Italian will and the English will could stand together so that his estate passed under the substitute gift instead of to his sister on intestacy. There was no implied revocation and thus no intestacy. ↩︎

Re Robinson [1930] 2 Ch. 332. ↩︎

Re Williams [1985] 1 WLR 905, 911-912. ↩︎

Re Segelman [1996] Ch 171. ↩︎

Lett v Randall (1855) 3 Sm & G 83. ↩︎

Towns v Wentworth (1858) 11 Moo. P.C. 526 ↩︎

Section 116 of the Senior Courts Act 1981, pre-grant. The court also has the power to remove an administrator after a grant has been taken under s. 50 of the Administration of Justice Act 1985. ↩︎

Forfeiture Act 1982 s. 1, 6. ↩︎

Forfeiture Act 1982 s. 2, 8. ↩︎