Pensions and Divorce – Which Valuation Should You Use?

One issue which crops up regularly when advising parties on the division of pension rights on divorce is how pensions should be valued, and in particular whether the cash equivalent transfer value (CETV or CEV) is appropriate for this purpose.

One issue which crops up regularly when advising parties on the division of pension rights on divorce is how pensions should be valued, and in particular whether the cash equivalent transfer value (CETV or CEV) is appropriate for this purpose.

The legislation

It is important to bear in mind that the legislation prescribes that CEVs should be used. Though it has scope for either party to bring evidence that to do so would be inequitable. So the CEV should normally be the starting point.

When does it matter?

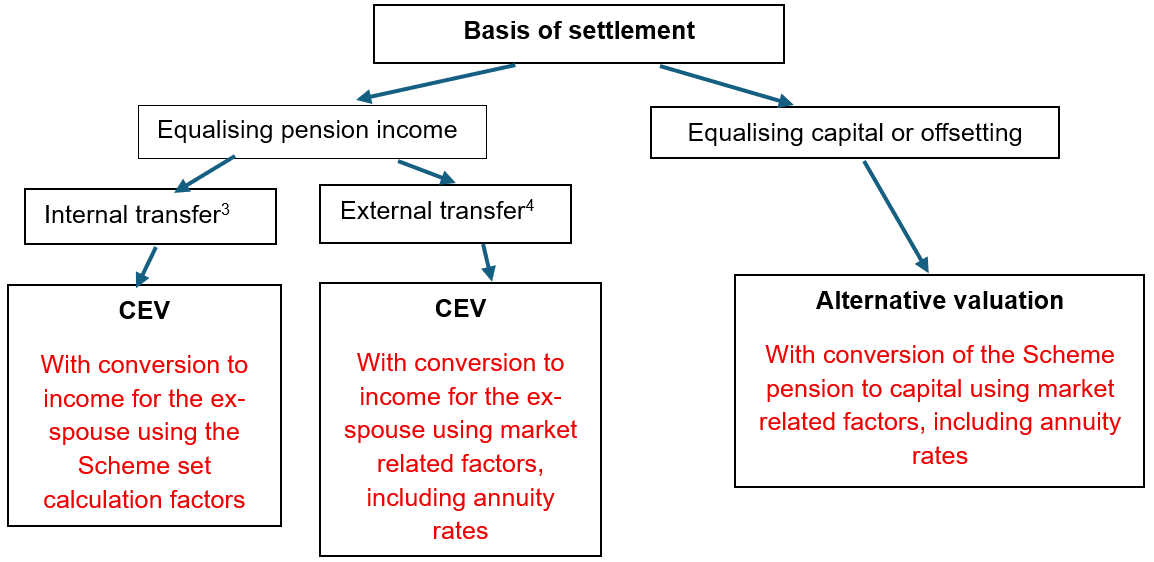

The means of settlement is key here. An alternative to the CEV only really needs to be considered if settlement is being considered by means of equalising capital values[1] or through offsetting.[2] If settlement is seeking to equalise pension income for the parties, there is no real need to consider any other valuation.

What about the type of pension?

For money purchase (or ‘defined contribution’) pensions, it is unusual for an alternative valuation to be needed. There will be occasional cases, for example particularly old insured arrangements, where this is not the case. But these exceptions tend to be quite rare.

There is a common misconception that public service pension scheme CEVs undervalue those pension rights. In fact the opposite is now generally true. This is due to two things – firstly the Government has revised their view (upwards) of the cost of underwriting these benefits, and secondly the market cost of securing a pension in the insurance market has come down as interest rates have risen.

So for public service pensions (which are almost all ‘defined benefit’ – the amount of pension being specified rather than being based on the value of the fund) the cash equivalent transfer value (CEV) may not be suitable if seeking to settle based on equalising capital or offsetting. This is also more generally the case for any defined benefit pension, and it is worth testing how close the CEV is to a market-related valuation.

And don’t forget State Pensions. The Department of Work and Pensions don’t provide a CEV for these. A valuation will be needed if these are being considered and the parties are looking to settle by equalising capital or offsetting.

Why are CEVs not suitable?

The legislation governing the calculation of a CEV is not divorce specific. It is premised on the original purpose of CEVs, which is to provide an individual with a fair amount of money which they may transfer to another pension arrangement. For defined benefit rights this involves converting the expected future income stream the scheme was expecting to pay into a current capital value. For this reason it offers a convenient means of capitalising that income for divorce purposes also. However, the legislation offers considerable flexibility in the calculation for private sector schemes. For public service schemes the Government base the calculation on a measure of economic affordability, which is unrelated to the measures used by other schemes.

When considering the capital values of parties’ pension assets in the round, some consistency is needed to ensure the appropriate weight is given to each arrangement. This is why an independent valuation of any defined benefits should be considered, so that those assets can be fairly compared with money purchase pensions and with the market values of any non-pension assets, if considering offsetting.

Valuation method

The Pension Advisory Group (PAG) offers guidance on the methodology which might be used. Most Pension on Divorce Experts use what is known as the Defined Contribution Fund Equivalent (DCFE) method when preparing an (alternative) valuation of defined benefit pension assets. It is also sometimes referred to under other names such as ‘the Replacement Cost Method’, independent value, assessed value or market value.

This method places a gross replacement value on a defined benefit pension, using similar assumptions to those used to estimate the income a money-purchase pension may provide. It involves making assumptions about the investment return expected pre-retirement, and the cost of securing annuity income at retirement. Whilst of course there is no guarantee these assumptions will be borne out in practice, they provide a mechanism for comparing different types of pension savings in a consistent manner.

Things to watch out for

The results of calculations seeking to equalise income or capital on divorce can be similar but can also be surprisingly different. This is because income equalisation considers the timing of pension payments to each party, whereas capital equalisation does not. An example of where a significant difference might arise is where one party is already in receipt of pension, perhaps having retired as a result of ill-health, whereas the other party would be unable to access pension income for some considerable time. This will similarly be the case for parties with large age differences, or involving schemes with very early retirement ages (as can apply in some of the public service schemes). Whilst the Pensions Expert will typically consider only pension income, the wider context of settlement will be relevant to how the calculated results are taken into account based on the circumstances of the case.

Don’t forget about tax

If pension assets are being compared with non-pension assets, any valuation should be adjusted for tax. That is to allow for the rate of tax expected to be paid by the owner of the pension asset in retirement. There can additionally be tax complications where the offsetting equivalent of a pension share is being determined, as in such circumstances, the tax position of the recipient of the pension share may also need to be factored into the calculations, to ensure that a fair outcome is achieved. Tax is also a complication for the parties depending on the relative mix of income and capital between them noting that capital amounts may sometimes be free of tax.

To summarise

In summary, the use of pension valuations in divorce settlement is a complex area. It is important that the objective of any settlement basis under consideration is taken into account when deciding what value to consider, and that the value assigned takes due consideration of the circumstances of the case, allowing for the types of pensions held, the means of implementing settlement (for example an internal or external transfer) and the tax positions of the parties post settlement.

Disclaimer: The views expressed here are the views of the writer only and do not necessarily represent the view of Actuaries for Lawyers. Whilst every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of the information in this post, it is important to always check the benefit rules with the schemes before making any financial decisions based upon these. Actuaries for Lawyers cannot be held responsible for any losses incurred as a result of relying upon information contained in the blog post as it does not constitute advice or act as a substitute for providing individual advice in relation to the specifics of a particular case.

Where the aim is to equalise the capitalised values of the parties’ pension rights. ↩︎

Where the aim is to consider the capitalised values of the parties’ pension rights together with their other marital assets, and potentially offset any inequality by one party retaining more non-pension assets. ↩︎

Where the ex-spouse becomes a member of the Scheme in their own right. ↩︎

Where a proportion of the CEV is transferred to an alternative pension arrangement in the ex-spouse’s name. ↩︎