Money Corner: EBITDA – The Valuer’s Measure of Profit

Published: 22/11/2024 06:00

It is often said that ‘valuation is an art, not a science’. Whilst it is undoubtedly true that value is in the eye of the beholder the reference to art rather than science should not be taken as meaning there are not right and wrong ways to approach the valuation of a business. There should be consistency between the approaches adopted by different valuers.

There are many different ‘right’ ways of valuing a business. The extent to which a particular method is the ‘right’ right way will depend on factors specific to the business, its future prospects and the sector in which it operates. When looking at the value of most trading businesses (as with most things, there can be exceptions to the rule), the ‘right’ way will include a multiple of profit (being the net income of a business over, usually, a year).

A valuation using a multiple of profit (or earnings) is commonly referred to as a ‘market approach’1 or ‘capitalised [insert profit measure here] approach’.

This article takes a look at the starting point in any valuation of a profitable trading business: profit/earnings.

The starting point

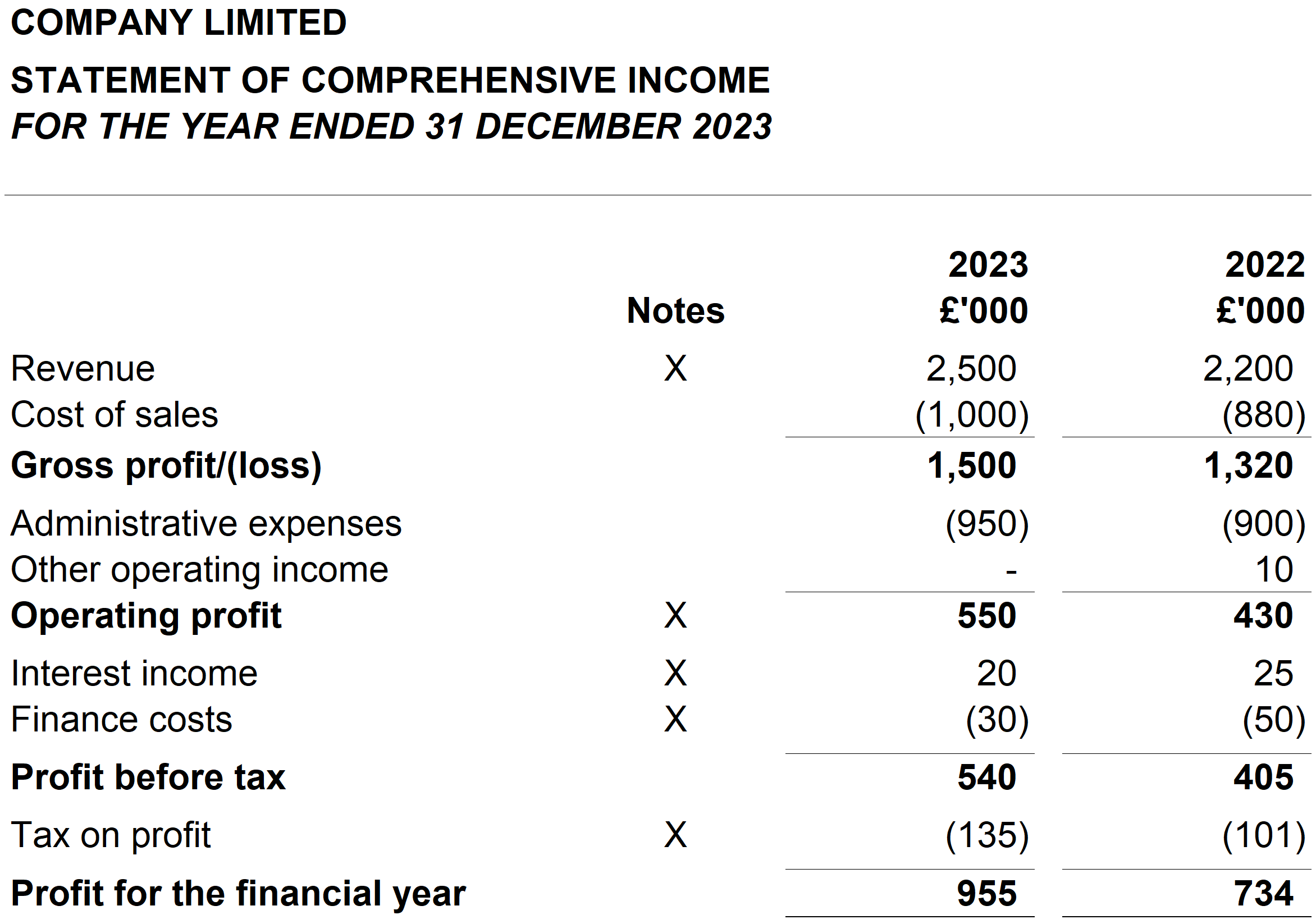

The starting point for understanding the profitability of any business is its ‘Statement of Profit and Loss’ (also referred to as the ‘P&L’, the ‘Statement of Comprehensive Income’, or the ‘Income Statement’).

The P&L is a high-level breakdown of the income generated and the costs incurred in the period. It is fairly standard in its structure and will usually set out the following measures of profit:

- Turnover (sales or revenue) – being the income generated directly from the business’ trade (net of VAT)

- Gross profit – being the turnover less costs directly attributable to its generation

- Operating profit – being gross profit less administrative costs (the overheads of the business such as staff costs, rent and rates) plus other operating income (e.g. if the business also owned property which it was renting out and receiving rental income)

- Profit before tax (PBT) – being operating profit less financing costs plus interest receivable

- Profit after tax (PAT) – being PBT less tax

Each of the above measures of profit can, in theory, be used in valuing a business. However, there is a more common measure, particularly in real world transactions involving owner-managed businesses. This measure is EBITDA.

What is EBITDA?

EBITDA is another measure of (annual) profitability although it is not reported in the P&L. It stands for:

- Earnings = profits (income less costs) before …

- Interest = costs of financing the company (through bank lending, hire purchase, invoice discounting, etc) and interest receivable (e.g. on cash deposits)

- Tax = corporation tax

- Amortisation = the cost of intangible assets such as software, spread over the period over which they will be used by the business. When fixed assets (either intangible or tangible) are acquired, their cost is initially recognised on the balance sheet of a company and the cost is spread through the profit and loss account as either an amortisation or depreciation charge over the useful life of the asset

- Depreciation = the cost of tangible assets, spread over the period of their life/expected use by the business as with intangible assets (above)

EBITDA ignores the impact of the financing structure and financing decisions of the directors to give an understanding of the underlying profitability of a trade on a basis which can be compared between entities. Two entities may have equal EBITDA but very different net profits because one may be financed by debt (thus incurring interest costs) whereas the other is financed by equity (with no interest costs). A valuation using EBITDA means the trade of these businesses will have the same value (the value of the shares will not be the same, however – more on that later).

It is important to understand that EBITDA reflects the profitability of the trade as it is currently being managed and does not seek to determine the optimum level of profitability.

How is EBITDA determined?

While not stated in the P&L, EBITDA can be fairly easily calculated from one of the profit measures of the P&L. Depreciation and amortisation are usually included within administrative expenses. EBITDA therefore most closely resembles operating profit and can, on a rudimentary basis, be calculated by adding back depreciation and amortisation to operating profit (the amount of depreciation and amortisation can usually be found in either the operating profit note or fixed asset note to the financial statements).

But it isn’t really that simple.

For the purpose of valuation, a valuer needs to determine a ‘maintainable’ EBITDA, namely that level of EBITDA that the business might reasonably be expected to generate in the immediately foreseeable future and from which a hypothetical purchaser would expect to benefit.

This is achieved through a review of recent historical (and sometimes forecast) EBITDA, which is adjusted for income and costs which are not expected to be received or incurred in future years (i.e. exceptional or one-off costs) and non-market rate costs.

Exceptional costs may relate to, for example, bad debts, profits or losses on the disposal of fixed asset, or litigation surrounding an employment dispute.

The most common adjustments for market rate costs are:

- Directors’ costs – directors (or other staff) who also own shares are often not remunerated at a market rate. They commonly either receive: a nominal salary, with the scope for a top-up via dividends or an increase in the value of their shares through reinvestment of income; or a higher than market rate salary at their own discretion. For valuation purposes, EBITDA needs to be adjusted to reflect a market cost, being the cost that a purchaser of the company would have to incur if they employed a suitably qualified third party (or parties) to manage it.

- Rent – where a company operates from property that it owns, or that is owned by its shareholders, it may be paying no or discounted rent. While there are certain exceptions, companies rarely need to own the property from which they operate. Consistent with the reasoning for directors’ costs, adjustment for a market rate of rent is therefore necessary.

In assessing the level of EBITDA that is ‘maintainable’, consideration of historical trends and future expectations is required.

There is no ‘common’ approach to the calculation of maintainable EBITDA – such as an average of the previous 3 years, or a 3:2:1 weighting of such. The approach should be specific to facts at hand, i.e. if the company has consistently grown year on year (with no expectation of a change in this trend) it is reasonable to assume that EBITDA will be at least that of the most recent year. If EBITDA has been stable year on year, it may be reasonable to assume that it will continue to be so.

Alternative measures of profit

A valuation does not exclusively require EBITDA as its measure of profit. Other profit measures may be equally (or more) appropriate (and a valuer may consider several approaches using different types of profits).

With each approach, an assessment is still required as to the level which is ‘maintainable’.

Turnover

As already mentioned, turnover (revenues or sales) represents the income (net of VAT) generated by a business from its trade (e.g. for a retailer, the income from the sale of goods; or for a law firm, the income from providing legal services).

A multiple of turnover is commonly used where the ‘selling point’ of a business is its revenue stream/customer base which can be serviced with minimal additional cost to the buyer (such as software as a service companies, where its income is derived from the leasing of software).

Common adjustments to ascertain a maintainable level include adjustments for one off or new contracts or recent changes to contracts which are not reflected in historical revenues.

EBIT

EBIT stands for Earnings Before Interest and Tax and is usually equal to operating profit.

A multiple of EBIT may be appropriate where the business being valued is required to incur significant capital expenditure on a regular basis (such as a freight or haulage business owning a fleet of vehicles).

An EBIT approach recognises the regular cost associated with the acquisition and maintenance of the equipment required for the generation of its income, through the depreciation charge put through the P&L, assuming this is a suitable proxy for the ongoing amount of capital expenditure required by the business.

Similar normalising adjustments as are required for an approach using EBITDA would also, likely, be required.

Valuations using a capitalised EBIT approach are not common due to the fact that they are only suitable for relatively few companies and information on EBIT deal multiples is limited (valuers may have to calculate implied multiples themselves).

Profit before tax (PBT)

A review of PBT year on year can enable the valuer to assess the profitability of a business without the impact of changes in tax policy or reliefs available. It is seldom used as a profit measure for valuation purposes.

Profit after tax (PAT)

PAT represents the ultimate profit of a business after taking into account all income and all costs (including tax). It is the PAT that is the profit available for distribution to shareholders, assuming that there are no accumulated losses from previous years.

A multiple of PAT is more commonly referred to as a Price/Earnings (P/E) approach.

A P/E approach does not seek to neutralise the financing decisions of the directors (reflected through depreciation, amortisation and interest charges, which are included within PAT) and therefore inherently assumes that the company is financed in the same way as comparable businesses. For this reason, and due to the fact that deals are no longer transacted based on P/E multiples, valuations using a P/E approach are less common.

Free cash flows

Free cash flows (FCFs) are the measure of profitability in a valuation using a discounted cash flow (DCF) approach (referred to by the IVS2 as an ‘income approach’), a valuation method whereby the valuation is determined as the current value of future cash flows.

Profit ≠ cash

Future FCFs are the inflows (and outflows) of cash to/from a business. As a starting point, a valuer will consider forecast EBIT and will adjust for expected net cash inflows (such as the recovery of debtors) and cash outflows (such as the payment of creditors, capital expenditure and tax) to determine the net cash movements of the business.

Future cash flows are discounted to reflect the risks and uncertainties associated with them on the basis that £1 in the hand now is worth more than £1 to be received (maybe) in one (or more) years. This is achieved through the application of a discount rate.

A DCF is most appropriate when a business is not in a steady state, often because it is young and/or growing or has a finite lifespan. However, a DCF approach requires robust, reliable forecasts (for a period of say 3–5 years). Many businesses (even of a ‘decent’ size) do not prepare detailed forecasts beyond the current or next financial year (if they prepare forecasts at all), making a DCF approach unviable in many valuations. Even where forecasts are prepared, they may be incidentally or deliberately under or overstated depending on the intended use of the forecast. Forecasts should therefore always be approached with caution.

There is a theoretical relationship between the discount rate and an EBITDA multiple (discussed below), so inability to adopt an income approach is rarely catastrophic.

The others

The above is not an exclusive list of the profit measures which may be considered in a business valuation. For example, hotels and care homes can be valued based on a rate per room.

The next steps

Whilst not the focus of this article, greater understanding of the differences between the different profit measures may be obtained from a basic understanding of their ultimate use in a valuation.

Once a reliable measure of maintainable profit has been concluded upon, a suitable multiple should be applied and adjustment made for assets and liabilities not associated with the direct operation of the trade to determine the overall value of the business:

- Maintainable EBITDA x multiple = Enterprise value (the value of the trade)

- Enterprise value + (cash + surplus assets – debt) = Equity value

Where:

- Enterprise value equals the value of the trade; and

- Equity value equals the value that is available to the shareholders of the company

The multiple, in brief

In calculating the value of the trade (the equity value) a multiple is applied to the concluded maintainable profits (being that EBITDA, revenues, etc).

The process of concluding on a suitable multiple is, arguably, the most subjective element of the valuation, and influencing factors will include the industry in which the company operates, its size, geography, trading performance, and factors specific to the company (such as a reliance on key individuals, a concentrated customer base or the development of a new product). Conclusions are therefore usually based on a combination of partially relevant data, namely: deal multiples for recent M&A transactions; trading multiples of public companies; and published non-industry-specific indices.

As already alluded to, multiple information is more readily available for some measures of profit, being EBITDA and turnover than for others such an EBIT or a PBT.

Generally speaking, the smaller the metric of profits, the higher the multiple. Thus, revenue multiples (applied to the highest profit figure of a company) will be comparatively small, while P/E multiples (applied to PAT, the smallest profit figure of a company) will be comparatively high.

Enterprise to equity adjustments

In corporate transactions, companies are commonly valued on a cash-free debt-free basis, assuming a normal level of working capital and adjusting for surplus assets (if any). This approach is based on the assumption that, immediately prior to a sale of the company, any surplus cash would be available to shareholders by way of a dividend and any long-term structural debt would be repaid.

For most valuation approaches (including capitalised revenues, EBITDA, EBIT and DCF approaches) adjustment is made for any assets and liabilities not directly associated with the trade, such as property and debt, based on the latest balance sheet position of the company.

A valuation using a P/E approach does not require this adjustment. As PAT is calculated after charges for interest, tax, amortisation and depreciation (the cost of financing the business and costs relating to the directors’ decisions to purchase rather than hire assets), no adjustments for net debt are required. However, surplus assets should still be addressed, for example if the company owns assets that are wholly unconnected with its trade. Examples include investment properties or the indulgences of the directors such as luxury yachts, collectable artwork and private jets.

Summary and conclusion

There are many different measures of profit that may be considered when valuing a business, with some more suitable than others (depending on the activity of the business and the availability of robust information). This article has run through the most commonly considered profit measure (EBITDA) and the usual alternatives (revenues, EBIT, PAT and FCFs). This should assist the reader to understand how the different profit measures compare and the rationale behind the adoption of different profit measures in a valuation.