Whose Fault Is It Anyway?

Published: 01/04/2022 06:19

The Divorce, Dissolution and Separation Act 2020, which comes into force on 6 April 2022, represents a significant and positive shift away from investigating reasons for marriage breakdown and towards individuals’ autonomy. Whilst very few practitioners oppose the introduction of no fault divorce,1 in certain quarters of the media the view has been expressed that if someone has behaved particularly badly in a marriage, there should be an outlet for the other spouse to shout that from the rooftops during the divorce;2 and there is concern that this may manifest itself in an increase in conduct allegations in financial remedy proceedings.

In this article, we review the significance of conduct in financial proceedings and argue that, whilst ‘fault’ has its place, there should not be a shifting of the tectonic plates to see judges being expected to adjudicate upon a growing tide of conduct allegations.

Although s 25(g) of the Matrimonial Causes Act 1973 refers to ‘conduct which it would be inequitable to disregard’ there is no statutory definition of conduct. We adopt the categories set out by Mostyn J in OG v AG [2020] EWFC 52 as to the distinct ways in which conduct can affect a financial outcome.

Preface: where conduct and needs align

Case law3 and our experience in practice highlight that even before considering the categories of conduct set out in OG v AG there is a broader sense in which the way in which parties have conducted themselves is relevant. To give a familiar example, a party who has developed depression and anxiety which are keeping her(/him) out of the workplace will have needs which s/he is unable to meet. Whether or not those circumstances have been brought about by – on one end of the spectrum – deliberate abusive and controlling behaviour by the other spouse or – at the other – without the other party’s culpability and even in spite of his(/her) care and support, the needs will be there.4

One way of advising and protecting the client who has been subjected to abusive behaviour is therefore to focus robustly on her needs – as a reason to depart from the ‘yardstick of equality’ – in light of the full impact the abuse has had on her future. It is important to be alive to the risk that a party who is vulnerable by virtue of an abusive relationship may accept less than s/he is entitled to in a desire to get things ‘over and done with’ and get out of a position of conflict.5 The Domestic Abuse Act 2021 introduces procedural safeguards, including the statutory presumption that parties who have experienced or are at risk of experiencing domestic abuse will be entitled to special measures in court proceedings.6 Nonetheless, it will continue to fall to practitioners to be appropriately trained in and recognise the hallmarks of abuse and ensure that victims are advised in a holistic manner as to their long-term needs in view of the impact of their experiences.

The OG v AG categories of conduct

Category one: ‘Gross and obvious personal misconduct’

Mostyn J identifies7 this category of conduct as the type referred to by Baroness Hale in Miller v Miller [2006] UKHL 24 as being appropriate to take into account only in very rare cases. Baroness Hale reasoned that: ‘it is simply not possible for any outsider to pick over the events of a marriage and decide who was the more to blame for what went wrong, save in the most obvious and gross cases’.

Indeed, it is difficult to find any example of a case (post-Miller) where an award has made a compensatory or punitive payment purely on account of a party’s behaviour towards the other party.8

At best, ‘pure’ conduct is treated as a looking glass through which to assess other s 25 factors.9 In R v B [2017] EWFC 33, Moor J found that the husband had engaged in a ‘complete and irrational obsession with avoiding tax’, which had caused him to commit tax evasion and fraud described by Moor J as a ‘financial catastrophe’ he had brought down on the family. As a result, he concluded that the husband ‘still has needs but they must be assessed in the light of what is available because of what he has done and the effect it has had on everyone concerned’. In principle, therefore, gross personal misconduct can be used as a lens through which needs and contributions are assessed, quite apart from being considered for its direct financial impact under the second category (below).

The case law therefore speaks to the importance of asserting the causal link between serious misconduct and the needs of the innocent party to be viewed through that ‘lens’. It is hoped that in light of Re H-N and Others (Children) [2021] EWCA Civ 448, the Family Court will be cognisant that in assessing ‘gross and obvious personal misconduct’ in the context of allegations of coercive and controlling behaviour and other forms of domestic abuse, it must draw together the strands of a pattern of behaviour, having regard to the definition of ‘domestic abuse’ contained in s 1(3) of the Domestic Abuse Act 2021.

Category two: Financial conduct – wanton and reckless dissipation

The principle when dealing with the second category of conduct was stated by Cairns LJ in Martin v Martin [1976] Fam 335: one cannot ‘fritter away or dispose recklessly’ of resources and then claim on divorce the distribution of a share as if one had behaved reasonably. A finding of conduct of this nature leads to the notional ‘add back’ – the ‘frittering’ party will be treated as having the money s/he would have had were it not for the way s/he behaved.10

Conduct of this category, too, is difficult to establish and fraught with uncertainty. The exact threshold to be met in order to make out ‘wanton and reckless dissipation’ is debatable. As commentators have noted,11 ‘wanton’ is a word capable of having several meanings. Meanwhile, ‘reckless’ is a term of art in criminal law, which the Family Court has not adopted in the current context as referring to a particular mens rea for reckless dissipation.12

The height of the bar of ‘wanton and reckless dissipation’ became perhaps as apparent as ever in MAP v MFP [2015] EWHC 627. In circumstances where the husband was found to have used substantial amounts of matrimonial assets on cocaine and prostitutes, Moor J held that as well as ‘deliberate, unprovoked, morally culpable conduct’, there will be ‘other situations where conduct justifies such a penalty, although such cases will undoubtedly be rare’. He said that although motivation is important, ‘a spouse cannot take advantage of all the good characteristics of his or her partner whilst disavowing the bad characteristics. To put it colloquially, you have to take your spouse as you find him or her.’ He therefore rejected the wife’s claim for sums to be added back, saying that the husband was ‘flawed’ like many successful people, and despite his actions being ‘morally culpable’ and ‘irresponsible’, his actions did not amount to deliberate or wanton dissipation.

Further adding to the shades of grey, Wilson LJ in Vaughan v Vaughan [2007] EWCA Civ 1085 held that the ‘obvious caveats’ to the add-back jurisdiction include that the fiction ‘does not extend to treatment of the sums re-attributed to a spouse as cash which he can deploy in meeting his needs, for example in the purchase of accommodation’. In cases falling short of ‘gross and obvious’ personal conduct but where there has been ‘wanton and reckless dissipation’, therefore, the Family Court, applying Vaughan, has been reluctant to trespass on the needs of the dissipator.13

Taking all of this together, the category of cases where the court will seek to achieve the equality the non-wasting spouse would have had were it not for the wasteful actions of the dissipating spouse is narrow. There is danger, even, that the test will be applied too narrowly. The apparent logic to the principle that in marriage one must ‘take the rough with the smooth’ belies the fact that the rewards of having a wealthy spouse are not inherently connected with the risk that one’s spouse may engage in deliberate unilateral decision-making as part of a pattern of behaviour which potentially amounts to economic abuse.

In light of growing understanding as to the forms controlling behaviour and economic abuse can take,14 there is a risk of unfairness if a spouse like Mrs MAP simply has to live with whatever poor financial decisions her husband makes on their joint behalf, because he is financially successful and ‘Many very successful people are flawed’.

Category three: litigation misconduct

According to Mostyn J in OG v AG, the correct place to reflect litigation misconduct is to penalise the guilty party in costs and it is ‘very difficult to conceive of any circumstances where litigation misconduct should affect the substantive disposition’.15 That follows the approach of the Court of Appeal in Ezair v Ezair [2012] EWCA Civ 893, which must be right in order to avoid ‘double penalty’ between costs orders and the substantive outcome.16

We do not propose to say a great deal about this area, which in itself opens a vast field of debate. We note only the potential impact of the amendment to Practice Direction 28A which took effect 27 May 2019 to include the further guidance that: ‘The court will take a broad view of conduct for the purposes of this rule and will generally conclude that to refuse openly to negotiate reasonably and responsibly will amount to conduct in respect of which the court will consider making an order for costs.’ It is hoped that in considering whether a party has ‘refused to negotiate reasonably and responsibly’, the court gives proper regard to the non-legal obstacles to settlement. For example, if a party can properly evidence that s/he has struggled to countenance entering a negotiation through fear, or has had difficulty engaging with the proceedings because of depression, burnout, or overwhelm, or in her proposals s/he has been more cautious about her financial security than otherwise may be expected, the court may well consider that s/he has negotiated ‘reasonably and responsibly’ in his/her particular circumstances.

Category four: the ‘evidential technique’ of adverse inferences

Finally, there is a category of cases where ‘conduct’ arises in financial remedy proceedings in the form of failure to comply with disclosure obligations. The court may then use the ‘evidential technique’ of drawing inferences as to the existence of assets.17

This category of conduct is notable in our context as a particularly powerful means of redressing unhelpful and obstructive behaviour. As identified by Wilson LJ in Behzadi v Behzadi [2008] EWCA Civ 1070, an adverse inference that a party holds undisclosed assets (in that case, a finding that the wife had beneficial interests in properties in Iran which she had attempted to alienate) can permit the court to find that she is capable of meeting her needs, while a notional re-attribution to that party of monies which have been dissipated (with a wanton element) may not.

Looking ahead: taking conduct seriously in financial remedy matters

In summary, the Family Court continues to have a number of items in its ‘toolkit’ for ensuring that a fair financial outcome can be reached in cases where one of the parties has mistreated the other in some way. Whilst the Family Court does not seek to quantify and remedy the misconduct in and of itself (for example by awarding a form of ‘damages’ to the innocent party), it can and will:

- View the innocent party’s ‘needs’ through the magnifying glass of the other party’s behaviour (in cases of ‘gross and obvious personal misconduct’);

- Notionally ‘add back’ to the matrimonial assets monies which have been wasted by ‘wanton and reckless’ dissipation by one party;

- Make costs orders to provide a remedy for litigation misconduct; and

- Draw adverse inferences – in potentially very broad terms – against parties who have failed to comply with their duty of full and frank disclosure.

Going forward, it is hoped that – particularly in light of growing awareness of the patterns of abusive behaviour – the Family Court will continue to use these tools to good effect, in the right cases, to grant fair financial outcomes to those who have been disempowered by the abusive behaviour of their spouses. In appropriate cases, practitioners should not shrink away from ‘conduct’ allegations which can be properly made out but raise them with a sharp focus on which tool in the toolkit can be used to redress the imbalance.18

Fears of an outpouring of conduct allegations in financial proceedings once no fault divorce comes in – is there cause for optimism?

Finally, a word on whether there will be a surge in conduct allegations in financial proceedings with the advent of no-fault divorce.

In the authors’ view, although this topic will be something of a watchpoint for practitioners and judges in 2022 and beyond, there is cause for optimism that there will not be a tsunami of conduct allegations in financial proceedings post-April 6. Among our reasons:

- As was clear from the Nuffield Foundation’s Finding Fault paper in 2017,19 public awareness of the ground for divorce and the need to apportion blame absent 2+ years’ separation was low. This was one of the reasons why the study concluded that retaining a fault-based system provided no deterrent to divorcing, as most people make the decision to divorce ignorant of that being the case. Indeed:

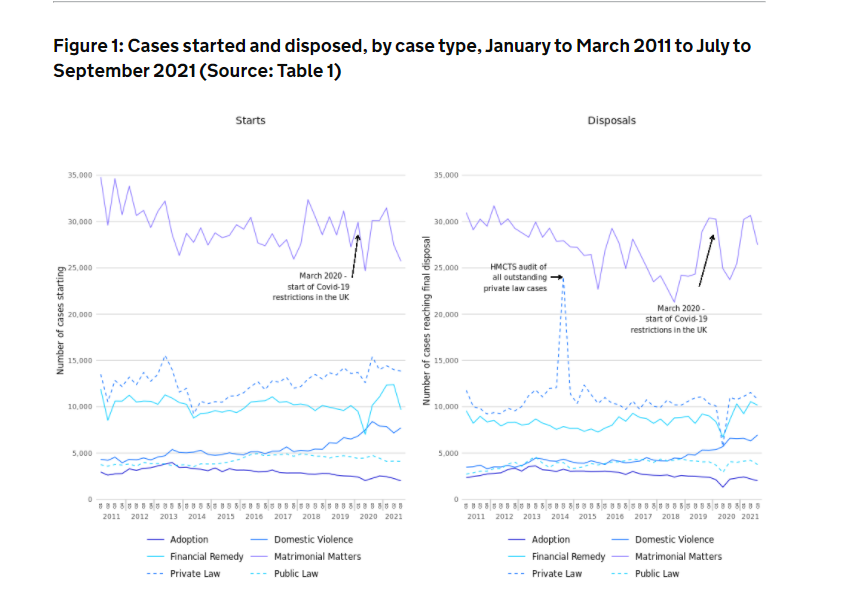

- Far fewer people pursue financial remedies than get divorced each year. The tables below show cases started and disposed by case type between January to March 2011 to July to September 2021:21

- There simply aren’t the resources to devote to more detailed investigations of conduct in financial remedy proceedings. Whilst the latest Family Court Statistics Quarterly bulletin showed volumes of new cases across all Family Justice areas decreasing in Q3 2021,22 possibly stabilising following the recovery from the impact of Covid-19, there continues to be an impact on timeliness measures. Care and supervision proceedings have increased further to levels seen at the end of 2012, with the average time to first disposal now 45 weeks, up 4 weeks year on year. Children Act cases more widely have also seen increases in the time to a first definitive disposal, with private law cases taking an average of 42 weeks, 9 weeks up from last year. Whilst there are initiatives such as the Family Solutions Group’s report What about me?,23 focusing on particular areas of the family justice system and diverting appropriate cases into non-court based dispute resolution, change takes time. In the meantime, judges are faced with robust case-management decisions and surely any evidence of an increase in frivolous conduct allegations would not be given airtime.

- More broadly, the government’s focus is on alternatives to court. In August 2021 the Ministry of Justice launched a wide-ranging call for evidence on Dispute Resolution in the Civil and Family spheres. The reasoning underpinning the project was clear – ‘litigation is still far from the last resort and too many cases still go through the court process unnecessarily. The provision of dispute resolution schemes remains patchy … [M]ore still needs to be done to increase uptake of less adversarial options.’ At the time of writing there has been no news of early findings and next steps, but it is a case of – watch this space. Again, one of the main drivers behind losing fault in the divorce process was the adverse impact that the need to apportion blame has on mediation and collaborative practice. To allow ‘fault creep’ in financial proceedings would have the same impact.

‘One of the arguments in favour of fault is that having to produce a reason for the divorce will act as a deterrent and hence protect marriages. There was little evidence in the study that that was the case … [T]here was no evidence at all that fault was protecting marriage. That is probably not surprising given gaps in the public understanding of the grounds for divorce and the ease with which a fault divorce can be obtained …’20

Therefore, it is unlikely that there is a big cohort of people lining up to divorce, agitating to file a behaviour petition full of venom who will, upon being told that that is no longer on the menu, decide to bring those sentiments into conduct allegations in financial proceedings.

Broadly speaking they show 2.5–3 times more divorce petitions than financial remedy starts (for the most recent period in respect of which we have statistics, Q3 2021, there were 25,587 petitions and 10,015 financial remedy applications). We know that c.55–60% of petitions at present are fault-based. What is more, our experience as practitioners is that very few want to apportion blame, but do so as they are told that they have no other (immediate) option. It is hard to see, therefore, that around 5,500 to 6,000 of the financial applications issued each quarter would suddenly see an injection of conduct allegations.

No fault divorce has been campaigned for by Resolution, the FLBA and others for decades, making 6 April 2022 a momentous date in the annals of family law. Whilst conduct in financial remedy proceedings has its place, it is to be hoped – and we suggest likely – that it will continue to be relied upon only in the narrow band of cases where it has its rightful place.