DR Corner: Mediation in the Wake of WL v HL – Low-Hanging Fruit or Golden Opportunity?

Published: 06/07/2022 07:13

Traditional perceptions of mediation

‘[M]ediated cases are self-evidently the easiest to settle; the low fruit of the dispute resolution world. Quite rightly this will always remain so. But my nagging concern about the mediation process remains; that one side often has the upper negotiating hand either psychologically or practically. Without independent, well trained and experienced, proactive intervention, the playing field can look and feel anything but level.’1

Sir Paul Coleridge’s analysis of mediation in the first issue of this journal perhaps reflects the views of many in the profession as to the merits and limitations of family mediation. But is this critique fair? This article responds to Sir Paul’s observations and seeks to address whether mediation is really only suitable for the easiest cases or is, in fact, a much under-used and more sophisticated process which, with an increasingly strained family justice system, we should all be seeking to embrace for the benefit of our clients.

2011 and all that – one decade on

The introduction of the pre-action protocol (PD 3A) under the Family Procedure Rules 2010 (SI 2010/2955) (FPR) in April 2011 was supposed to herald a sea-change in the approach to family mediation with the requirement that an applicant in a financial remedy application should, in default of meeting one of the defined exemptions, attend a Mediation Information and Assessment Meeting (MIAM).

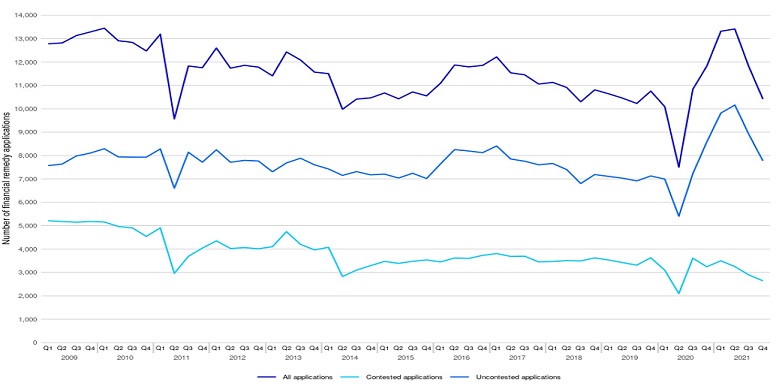

While there is little doubt that many more separating couples have become aware of family mediation since 2011, the graph in Figure 1 from the latest Family Court Quarterly Statistics (extending to the end of 2021) suggests that the number of contested financial remedy applications has remained at a very similar level (save for a dip at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic) over the decade from 2011 to 2020. The figures for 2021 do, however, suggest a slight reduction in contested financial remedy applications. Is this a sign that non-court resolution methods may be gaining traction, and that, going forward, we may see a reduction in the numbers of contested financial remedy cases coming before the courts? Alternatively, is this just a quirk of COVID-19?

Figure 1: Ministry of Justice, Family Court Statistics Quarterly, October to December 2021

Quite why mediation has not taken off over the last decade as many had hoped is not entirely clear. There is little doubt that some cases are patently not suitable for mediation and do require court intervention. Where there is recalcitrant non-disclosure, an unbending unwillingness on the part of one party to engage realistically with legal advice or substantial coercive control, mediation is unlikely to be suitable.

There are, however, still plenty of financial remedy cases coming before the courts where mediation is not being considered when it could be. Whether this is due to reluctance on the part of some solicitors to positively endorse the benefits of mediation, or failure by some tribunals to properly exercise their responsibility under FPR 3.3(2) to consider whether a MIAM has even taken place, the introduction of MIAMs has not led to a surge in mediation, or to pressure on the court system being relieved as had been hoped. The report of the Farquhar Committee of September 20212 reported that the average case length for financial remedy cases in 2019 up to financial dispute resolution (FDR) hearing was 55 weeks, while it took 84 weeks to reach final hearing – the delays were longer still in 2020. This plainly demonstrates a system that is working under enormous strain.

Sir Paul’s observation that private alternative dispute resolution as a whole is a much under-used process is undoubtedly true (although there has been a notable growth in the number of private FDRs), but is his suggestion that mediation is ‘the low fruit of the dispute resolution world’ a fair one?

Lawyer inclusive and hybrid mediation

In lower value cases there is little doubt that mediation is often the low fruit, or indeed the only viable fruit available to the parties. However, the categorisation of mediation as the preserve of only lower- to medium-value cases, or those which are easiest to settle, does not take on board significant progress in the development of the mediation model over the last decade.

Sir Paul identifies as a ‘nagging concern’ the issue of power imbalance, be it psychological or practical, that pertains to many cases. In the vast majority of cases that we see as family practitioners, there is indeed a degree of power imbalance; however, this does not render all of these cases unsuitable for mediation.

Mediators have extensive training in handling power imbalance, practiced and polished over many years. There are, of course, many excellent mediators who combine their mediation practice with varied and extensive financial remedy practice, as solicitors or barristers.

Significantly, the last 2 years have seen a substantial increase in the number of family mediators trained by Resolution to undertake hybrid mediation. Only 33 hybrid mediators were trained prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. However, over the last 2 years, a further 50 mediators have trained in this process and, taking on board those scheduled to train in the next few months, the total number of hybrid mediators will reach 100 later this year. Although in the past some mediators have, on occasion, involved lawyers in the mediation process, by inviting them to meetings, the hybrid mediation model has the involvement of lawyers at its very heart.

Hybrid mediation sees clients attending meetings with their lawyers present, often throughout the mediation process. It is a flexible model, where clients and lawyers can attend either in person or virtually. In both instances, meetings can take place with all parties together in the same room, or with part or all of the process conducted with the parties in separate rooms with their respective lawyers (with the mediator ‘shuttling’).

The major distinction between hybrid and traditional family mediation is that in hybrid mediation, the mediator is able (with the consent of the parties) to hold private meetings with each party and their lawyer and, in this setting, to ‘hold confidences’. These separate meetings can help the mediator to clarify issues and understand where synergies may arise and where it may be possible to break an impasse in negotiations.

A greater range of cases

Where there is a concern that the power imbalance may be too great for traditional mediation, hybrid mediation provides a real and attractive alternative for all parties. Some clients who might be nervous or overwhelmed by the prospect of meeting their spouse alone may feel safe to enter into the solicitor-inclusive model, in the knowledge that they will be supported throughout.

The flexibility of the model and the involvement of supportive solicitors throughout the process means that hybrid mediation can also be a realistic option for high conflict couples or situations where either or both parties may have autistic traits or personality disorders. These cases may not, on some occasions, be suitable for the traditional mediation model, but hybrid mediation opens up a viable non-court avenue.

As such, hybrid mediation can be used for a far greater range of more complex financial remedy cases than many often consider suitable for mediation. In addition to embedding the role of supportive solicitors at the heart of the process, the hybrid model enables the parties to agree to involve other professionals to advise within the mediation, including financial neutrals, single joint valuers and tax specialists. In short, it is a bespoke model, highly adaptive to the parties’ needs and circumstances. It can also be used successfully to deal with other family issues, such as inheritance or family business disputes.

The end of silos?

One criticism of many dispute resolution models (including the court process) has been that couples have not been able seamlessly to navigate the right approach for their case, instead being driven by professionals into an approach that is ‘siloed’.

Developments in the mediation arena, including the rise of the hybrid model, suggest we may be entering a ‘silo-free’ era. The hybrid mediation model is similar to the collaborative law model, in that it is an interdisciplinary approach, with the couple supported by a range of professionals in finding the right outcome for their situation.

In addition to family solicitors, financial professionals and family consultants, hybrid mediation allows for the involvement of counsel. Both as a solicitor and as a mediator, I have conducted a number of mediations where counsel has been involved in supporting the process by giving advice to individual parties between sessions. Counsel can, of course, also be involved in giving an early neutral evaluation to both parties on one or more issues.

In addition, couples can move seamlessly from hybrid mediation into arbitration if they have reached an impasse on one or more issues. What is more, there is nothing to prevent a couple who have reached an impasse from choosing to have a private FDR.

In short, hybrid mediation is a highly flexible, interdisciplinary, de-siloed model which enables parties to reach agreement in the optimum way, utilising whatever professional support they need in whatever is the right setting to achieve this (and, if necessary, moving seamlessly to another setting).

WL v HL – looking forward

Another factor which suggests a much more positive outlook for mediation is policy activity on the ground.

The November 2020 report by the Family Solutions Group3 featured, among other elements, the Surrey Initiative, developed by mediator Karen Barham. This set out a roadmap requiring far greater engagement in non-court resolution by professionals, including a requirement that both parties consider non-court dispute resolution options and if the respondent refuses, a requirement to explain why.

This work has since been built on by Karen Barham, Martin Kingerley QC and Rhys Taylor through the Family Solutions Initiative, which emphasises a shift away from ‘dispute resolution’ to ‘solution-focused’ processes. The suggestion that costs sanctions may be imposed (even on lawyers) in some circumstances where parties refuse to engage in non-court dispute resolution is perhaps controversial for some; however, this influential group’s work suggests further change and that greater incentivisation of mediation and non-court dispute resolution is likely going forward.

The movement towards a more proactive approach to non-court dispute resolution and mediation was borne out in the decision of Mr Recorder Allen QC in WL v HL [2021] EWFC B10 (5 March 2021). In that case, the judge used his case management powers under FPR Part 3 to stay proceedings to enable the parties to engage in non-court dispute resolution. He did so on the basis that the costs incurred by the parties and the estimated future costs were disproportionate to the issues he had to determine.

To add bite to his decision, when adjourning the matter Mr Recorder Allen QC ordered the parties’ solicitors to write to him setting out the parties’ engagement in non-court dispute resolution, together with a schedule of any offers made and replies to offers made. Further adjournments were subsequently granted, as the solicitors reported by way of joint letters that the parties were engaging in mediation and were hopeful of coming to an agreement. A substantial agreement was then reached, save on a discreet issue that was determined by Mr Recorder Allen QC on paper.

Mr Recorder Allen QC stated in his judgment that he was ‘confident that adopting the approach I did led to a better, quicker and less expensive outcome than would otherwise have been the case’ ([26]). He referred to his duties to further the overriding objective at FPR 1.4(2)(f) to include ‘encouraging the parties to use a non-court dispute resolution procedure if the court considers that appropriate and facilitating the use of such procedure’ ([27]).

The encouragement at the highest levels of the judiciary of a more proactive case management approach is underlined by the fact that Mostyn J, as then lead judge of the Financial Remedies Court, asked the judge to record his use of FPR Part 3 powers in a written judgment published on BAILII (on 5 March 2021).4 This case may come to be seen as a pivotal moment in terms of judges being encouraged to be much more proactive and constructive in the exploration of non-court resolution options and use of their powers under FPR Part 3 in future.

Online solutions

‘I have found mediation via Zoom far from satisfactory or easy. The process is inevitably very drawn out and ease of communication, a vital key to smooth and successful mediation, is severely hampered.’5

Sir Paul’s comments on the merits of online mediation will not be shared by many mediators. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the vast majority of mediators had done little, if any, online mediation. Throughout the subsequent 18 or so months, however, the status quo was transformed and almost all mediation work went online.

While the reopening of society will, no doubt, lead to the resumption of face-to-face mediation for some couples, contrary to many mediators’ expectations prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, online mediation has been a revelation in its effectiveness. In some respects, it even has distinct advantages over its face-to-face cousin.

Sir Paul’s critique of the process as ‘drawn out’ is, I believe, misplaced. To the contrary, meetings are much easier to arrange. Parties are able to dial-in (within reason) from anywhere, from an office meeting room, a hospital consulting suite or the comfort of their own home, and at much shorter notice if required.

Online mediation can also lead to much quicker turnaround times, given there is no need to travel – with the consequent removal of geographical boundaries. Like many other mediators, I have successfully mediated a large number of cases across the United Kingdom and even abroad via Zoom, which did not happen on anything approaching this scale prior to the COVID-19 pandemic.

The suggestion that Zoom is only for straightforward cases is not borne out by the mediators I speak to. Hybrid mediation, in particular, is highly effective via Zoom. I have successfully conducted a number of hybrid mediations, including cases with substantial assets and complex financial issues.

Mediating on Zoom (or other online platforms) has many distinct advantages, not least the ability to share complex financial data in real time via ‘screen share’. The parties can work on figures collaboratively and the mediator can show multiple resources at the click of button, rather than having to struggle with bundles of papers.

In addition, online mediation benefits those parties who might otherwise feel uncomfortable or unable to cope with face-to-face mediation (even where shuttling is involved, as they may not want to be in the same building). It enables participants to take part from the safety of their own home or another venue. And, when one party is behaving inappropriately, the mediator is able to mute participants or separate them into the private space of a ‘breakout room’ at the click of a button.

‘Fairness’ can be subjective

Sir Paul writes that ‘mediation is ... limited in its usefulness unless the case is straightforward, and all parties are in an a very fair and balanced frame of mind’.5

As any mediator will attest, ‘fairness’ is a highly subjective term (particularly when, for example, considering needs), which parties invariably perceive differently. As such, this suggestion does not ring true.

Parties invariably view fairness through different prisms; there are, moreover, some power imbalance issues in almost every setting where relationships end and mediation begins. The skill of the mediator is, of course, to provide impartial support, help the parties to reality-test options and look for synergies, so that practical solutions can be found which parties can settle on (regardless of how they may have initially viewed the question of ‘fairness’).

Final thoughts

Mediation provides a golden opportunity to alleviate the burden on the overburdened court system, if only more practitioners and judges embrace it. What can be done to ensure that this opportunity is taken?

- Compliance with the MIAM protocol should, a decade on, be properly followed, not just by solicitors but also by mediators and judges. As a matter of good practice, a mediator should always invite not just the applicant but also the respondent to a MIAM. Sadly, some mediators have been too willing to sign off forms where only the applicant has been invited to a MIAM. There is no compulsion on the parties to proceed with mediation, but all mediators will attest to the fact that plenty of mediations referred as a ‘tick-box exercise’ by the applicant’s solicitors have turned into successful mediations when the respondent is also invited.

- In light of the decision in WL v HL, there should be no further excuse for judges to fail to follow FPR 3.3, which requires them to ask about mediation/non-court dispute resolution at every court hearing (all too often, this does not happen). The example of WL v HL suggests that mediation could and should be the subject of a far greater level of judicial encouragement and intervention. In the same way that a proper policing of the MIAM protocol would likely lead to a significant reduction in the numbers of financial remedy cases coming before the courts, a roll-out of the approach adopted by Mr Recorder Allen QC in WL v HL may lead to a significant number of cases being adjourned while parties explore mediation or other forms of non-court dispute resolution, thereby reducing pressure on the court system.

- Training in the benefits of mediation (and the importance of complying with the FPR) should not stop with judges. The Family Solutions Group report recommended that all family law professionals undertake awareness training in non-court resolution options. Over time, such training could lead to many more cases being diverted away from an overburdened court system into non-court dispute resolution routes, such as the hybrid mediation model.

It will be interesting to see how the evolution of a two-client, one-lawyer model (should it obtain broader regulatory approval) may further stimulate the development of private non-court dispute resolution. Could such a brave new world see the rise of evaluative mediation, where mediators adopt a directive approach to mediation, rather than the current facilitative model adopted by most?

Alternatively, given that a core strength of the facilitative mediation process is the calm impartiality of the mediator, who helps the parties ‘reality test’ a range of outcomes, might any shift to a more evaluative approach in family mediation be less likely than many may think?

As the number of cases awaiting resolution in court grows even more unwieldy, creative developments in mediation mean that there is a route to resolution even in the most complex of cases.