The Role of Opt-out Agreements in Cohabitation Reform

Published: 30/06/2025 06:00

There is a significant measure of agreement amongst both academics and practitioners that making financial remedies available to cohabiting couples on an opt-in basis will not work.1 It will do little to help those in religious only marriages who are left exposed upon separation. It will do little to help those who mistakenly believe they have legal recourse because of the common law marriage myth. Neither will it help couples aware of their options under the law, but who cannot agree, or simply never get around to opting in. In all these scenarios, where the opt-in does not work, it is the most economically vulnerable cohabitants who lose. They would be no better off than under the current, ineffective web of property and trusts law, which for many, could mean poverty.

The alternative is a system of financial remedies that cohabitants may opt out of. This was proposed by the Law Commission in 2007 and was also endorsed by the Women and Equalities Committee in 2022.2 But what does opting out entail? This article explores the nature and scope of opt-out agreements. It first looks to the Scottish experience, where opt-out agreements are currently possible under the law. It then turns to the need for opt-out agreements to have safeguards and looks to the insights that nuptial agreements can provide for cohabitation agreements in this regard.

Opt-out agreements in Scotland

In contrast to the absence of a regime for cohabitants in the rest of the United Kingdom, there is some financial relief available to cohabitants on relationship breakdown in Scotland. The Family Law (Scotland) Act 2006 introduced remedies for cohabitants on separation and death. The basis of relief is to redress unequal outcomes, accounting for economic advantage and disadvantage, as well as the economic burden of caring for children. There is no requisite minimum period of cohabitation to be eligible for relief; cohabitants simply must have lived together as spouses or civil partners. Relief, however, is limited to payment of a capital sum, and applications are time-barred to one year after the parties cease to cohabit. Thus, while better than England and Wales, provision still does not redress serious financial hardship, and the scope of claims is inflexible.3

Key to Scotland’s current provision is the possibility for cohabitants to opt out of it. The context of opt-out agreements in Scotland is very different from that of cohabitation agreements south of the border, for the purpose of such agreements is to disapply or waive any claims to financial remedies on separation. Essentially, parties are opting out of a (limited) right to ameliorate relationship-generated disadvantage on relationship breakdown.

This has echoes of how nuptial agreements operate in England and Wales. Provision for separating cohabitants in Scotland differs greatly from the wide range of remedies available to divorcing spouses in England and Wales. However, while the specifics of what is being opted out of are different, the general gist of each agreement is to prevent the economically disadvantaged partner from making future claims (or, in the case of a nuptial agreement in England and Wales, from doing so in an unbounded way).

It is perhaps surprising then that there are no particular formality requirements for opt-out cohabitation agreements in Scotland. As Jo Miles et al have observed,

‘Scots law is apparently content to allow an individual to waive a pecuniary claim without imposing any particular formality requirements for doing so or subjecting that decision to closer scrutiny than the general law would afford.’4

Opt-out agreements in Scotland are thus treated like any other contract and there is no family law jurisdiction to set them aside.

There are evidently some concerns about there being no special family law oversight of an agreement which could represent a lesser income-producing partner signing away her future right to be compensated for relationship-generated disadvantage. And so, in addition to cohabitation law more generally,5 this was reviewed by the Scottish Law Commission in its 2022 report.6

Reform was proposed whereby an agreement could be varied or set aside for being unfair or unreasonable at the time it was entered into. This would provide the court with limited power to check the fairness and reasonableness (terms which are not defined by the Commission’s Bill) of the agreement at a particular moment in time. The Commission also decided not to suggest any specific formalities beyond standard contract law. Furthermore, should a cohabitation contract later become unfair or reasonable, the court will not be able to vary it or set it aside, and will be required to make an order consistent with its terms. It would therefore be the responsibility of the couples themselves to vary an agreement according to changing circumstances.

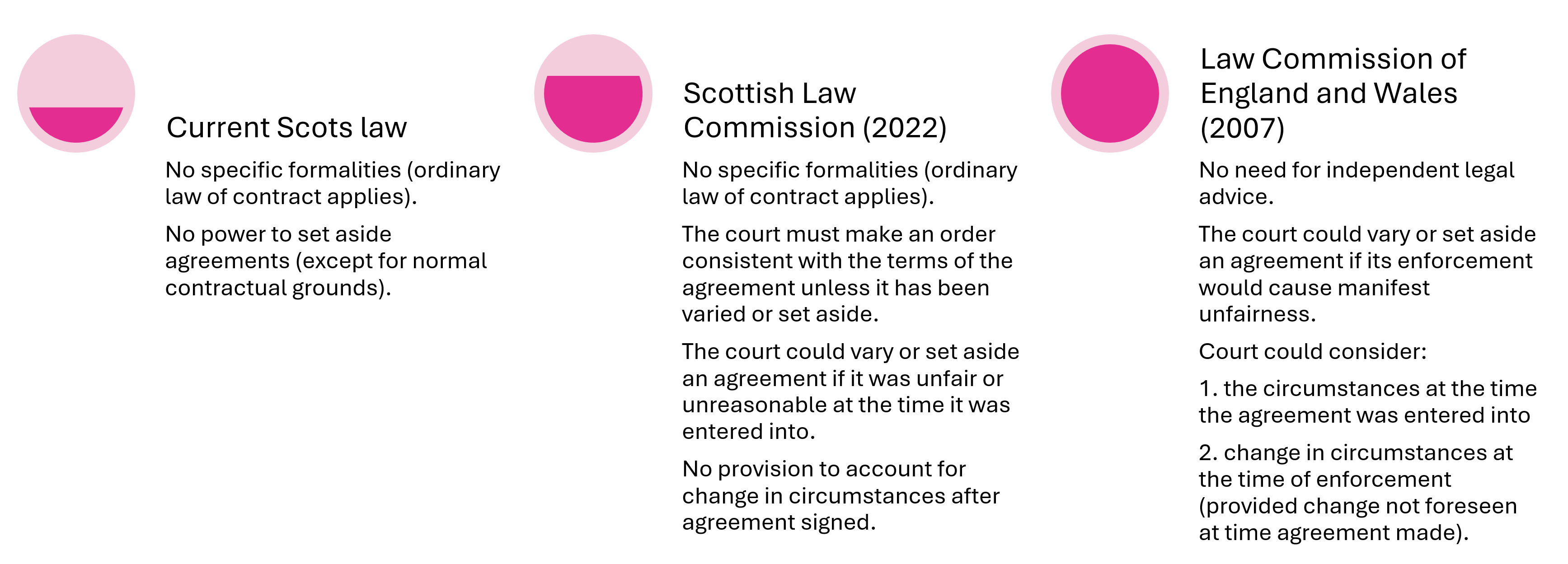

When comparing these recommendations with both the current law in Scotland and proposed reform in England and Wales, the different potential powers for the court to adjudicate cohabitation agreements is apparent. The reform proposed by the Law Commission of England and Wales in 2007 is contingent upon the introduction of an opt-out scheme of financial remedies for cohabitants.7 As shown in Table 1, a notable difference between the reform proposed in Scotland from that in England and Wales is the latter’s provision to account for changes in circumstance.

Table 1: Opt-out agreements: from fewest to most safeguards

Note: in addition to opting out of financial remedies, in all cases agreements may also clarify redistribution of assets in the event of relationship breakdown.

This difference might appear to be more significant in theory than in practice. The Law Commission for England and Wales stipulated that a change in circumstance must not be foreseeable. However, some circumstances might be entirely foreseeable yet nevertheless produce economic hardship. For instance, person A and person B decide to enter into a cohabitation agreement when they begin cohabiting, which opts out of financial remedies but does not make provision in the event of one party sacrificing career opportunities to care for children. This type of change in circumstance might be considered foreseeable, and therefore according to the Law Commission’s recommendations, would not fall within the remit of relevant change in circumstances.

There may also be unintended consequences and inequalities arising from the Scottish Law Commission’s decision to limit the fairness and reasonableness check to the time the agreement was entered into. The potential impact this could have on parties to cohabitation agreements will inevitably depend upon the context in which the contract is signed. A couple may make different decisions regarding their agreement depending on whether they create it 2 years or 15 years into their relationship.

As a result, if there is to be an opt-out system in England and Wales, careful consideration will need to be given to safeguards to prevent exploitation and injustice.

The importance of safeguards

It is often said that the law treats cohabitants as if they were strangers. And so, if there is reform that recognises the reality of family life for cohabiting couples, it would be rather counter-intuitive if the agreements opting out of financial remedies were based upon contractual principles that apply in the normal course of business.

It is vital to consider appropriate safeguards for opt-out agreements in the event of reform. The imbalance of power between couples making intimate agreements is well documented. Research repeatedly shows that wealth allocation is linked to the way power is distributed between parties entering intimate property agreements such as cohabitation contracts, as well as gendered power within relationships more generally.8

In short, it may be said that cohabitation contracts can theoretically promote autonomy, but whether such contracts realistically facilitate the exercise of autonomy on the part of both parties depends upon whether there is equal bargaining power in the relationship.

Cohabitation agreements have the potential to build safeguards for cohabitants weakened financially on separation after years of mingled assets, interdependency and unpaid labour, inequalities that are often gendered. And opt-out agreements do not simply have to opt out of a system of financial remedies. They can also provide scope for clarifying what the parties do want to do with their assets in the event of relationship breakdown. Agreements can provide a sense of security; a plan for what will happen in the event of serious illness, death and even retirement. Some commentators have therefore suggested that cohabitation contracts ought to include a background section outlining the intentions of the parties and the purpose of the agreement, and this is currently practised by some lawyers in England and Wales.9

The inclusion of a clause stipulating why the parties decided to enter the agreement provides potentially valuable insight into why couples enter cohabitation agreements in this jurisdiction. Even more, it requires the parties to be explicit with one another and to put in writing what they perceive the purpose of the agreement to be. And so, recognising the value of this potential to include the parties’ intentions is important. For if a scheme of financial redistribution is introduced for cohabitants in England and Wales with the mere ability to opt out, this practice of providing a background or rationale for the agreement may be lost. This context is often lost for other contracts such as nuptial agreements too, where the purpose is assumed: to determine the division of assets in the event of death or divorce.

Lessons from nuptial agreements

Unlike cohabitation agreements as they are now,10 nuptial agreements operate to avoid the discretionary decision-making power of a judge to consider the parties’ circumstances and determine an outcome that is fair, or sometimes to focus the exercise of discretion within narrower bounds. However, they can provide insight into opt-out agreements. While still different contextually, the core purpose of both nuptial agreements and opt-out agreements is to protect property in the event of relationship breakdown. Since nuptial agreements have routinely been given effect in England and Wales since 2010, there is much more case-law and research on how the economically vulnerable party can be protected. Nuptial agreements must satisfy the Radmacher test,11 whereby an agreement must be fair when made and not unfair at the time it is given effect. In practice, satisfying this test means significant weight is attached to legal advice and disclosure during the drafting of the agreement, and whether the agreement will meet the parties’ needs on relationship breakdown.12

The second, fairness-based prong of the Radmacher test operates as a substantive safety net, enabling the court to ensure that, despite changed circumstances over the course of the relationship, the needs of the parties are still met. This contrasts starkly with the Scottish Law Commission’s suggestion that while agreements must not be unfair or unreasonable at the time of drafting, no safeguards are necessary at the time the agreement is brought into effect.

Yet as my research suggests, safeguards at the time of enforcement can be a very important means of ensuring fairness at the drafting stage.13 In a study on unreported nuptial agreements with barristers and FDR evaluators, I was told more than once that the fairness requirement for nuptial agreements could be used to convince the wealthier party to be more reasonable:

‘you can say to them, you can’t screw them into the ground like this. It’s not going to work, because the court will let them out at the other end. So, you’re going to have to, for example, put more money on the table, because otherwise this isn’t really worth the paper it’s written on. If you say [in the agreement] you go away with absolutely nothing, regardless of children and lifestyle and everything, the court’s not going to think that’s fair. So, you can use that at the beginning to say to your … client, you need to put more into this, or it needs to be sort of more locked into a reasonable approach. And that generally works.’

From this perspective, having a safeguard that ensures consideration of the effect of the agreement on enforcement is one of the only sources of power currently available to the lesser monied party, because it provides her with leverage to negotiate, while incentivising the financially stronger spouse to agree to more equitable terms.

But – as in the case with opt-out agreements in Scotland – if there is no fairness safeguard, there will be individuals who cannot be persuaded to negotiate a reasonable opt-out agreement, and the consequences for the financially vulnerable party could be dire.

Application to opt-out agreements

There is no reason why safeguards similar to those applied to nuptial agreements cannot be applied to opt-out agreements. The specifics of these safeguards would depend upon the framework of financial remedies put in place for unmarried cohabitants. However, it makes sense to require at least two. First, independent legal advice. This can help ensure parties understand the contract and provide proper disclosure, and vitally, that they are aware of the consequences of waiving any financial protection that a general scheme for cohabitants may provide. Furthermore, legal advice can help cohabitants entering cohabitation agreements to be encouraged not to act according to their own self-interest, but instead to be equally empowered to agree to guarantee mutual financial benefits on separation. Competent advice can also help safeguard against exploitation, although the experience of nuptial agreements shows that such agreements are nevertheless still tainted by power imbalance.14 Still, imposing legal advice as a requirement could be an important means of helping the lesser monied party to refuse to accept (unquestioningly) what the other party wants and to refuse to give in to terms that will disadvantage them.

Secondly, cohabitation agreements could borrow from the law on nuptial agreements and include a minimum level of protection, whether this is that the parties cannot be left in a predicament of real need while the other party enjoys a sufficiency or more,15 or that the parties cannot contract out of meeting one another’s needs if they have a child. It is well documented that Schedule 1 provision under the Children Act 1989 creates indefensible economic inequalities between parents and children based upon marital status.16 And if reform is taken forward on the basis that the law can no longer facilitate this sort of discrimination, then it is critical we do not reintroduce this discrimination through an opt-out agreement.

An established irreducible minimum could be combined with an opt-out agreement being invalidated by the birth of a child, since statistically, parenthood is one of the greatest sources of financial inequality in family life.17

Future possibilities

There are many varied relationship dynamics within the category ‘cohabitant’, and so the purpose of any cohabitation agreement depends, of course, upon its context. This includes the economic circumstances of the parties, the relationship between the parties, and how that relationship changes between the time the agreement is signed and the point of separation.

Despite this variation, intimate relationships tend to be characterised by economic interdependence. Yet because there is no regime of property distribution on relationship breakdown that appreciates this dynamic, the law is letting down families and exacerbating economic inequality. Cohabitation agreements alone cannot provide redress. Some are sceptical about the need for reform in England and Wales given that cohabitation agreements already present an option for autonomous self-protection.18 However, contract law is a wholly ineffective substitute for the law’s failings, particularly given the widespread and deeply embedded belief in the common law marriage myth, combined with the fact that so few cohabiting couples create agreements.19

Nevertheless, exploring the possibilities for cohabitation agreements as part of potential future reform is important and worthwhile. These contracts need to be viewed as living instruments, that can document the broader context of parties’ decisions. In this way, they have the potential to account for changes in circumstances and can record the parties’ intentions at the time of drafting. This potential might be more limited for opt-out agreements, especially if the contract simply disapplies a scheme of financial remedies without making alternative arrangements. But it is important to learn both from Scotland and from nuptial agreements in England and Wales, so that appropriate safeguards can be built into reform.

Much has changed since the Law Commission’s 2007 report. New research and broader comparative experience20 mean there is now no excuse for neglecting to consider the operation of opt-out agreements in the event of reform. Simply providing for opt-out agreements that waive all protection and with no safeguards beyond normal contract law is unjustifiable given what we know about how power is exercised within intimate relationships. Indeed, failing to learn from Scotland’s mistakes is inexcusable. If the law is finally going to stop enacting this fallacy of treating cohabitants as strangers, it must also avoid letting such intellectual dishonesty through the back door. And so, it is crucial that opt-out agreements attached to future reform treat the parties as intimate partners, and not business partners.