Family Law – Not the Poor Relation

Published: 25/08/2022 15:42

Paper delivered (remotely from France) by Hon Mr Justice Mostyn to the 19th National Family Law Conference, Adelaide, South Australia, on Tuesday 16 August 2022.

1. My proposition is that family law is not the poor relation when it comes to resolving complex financial issues between adults who happen to have been married to each other (or, in your jurisdiction, who have cohabited for two years or have had a child together).1

2. Far from it. I would argue that, at least in relation to financial cases, it is a full-blooded member of the legal family, and does not occupy some kind of desert island or legal Alsatia,2 as critics persist in alleging. However, as will be seen, in children cases there are prolonged holidays on the island. I am going to concentrate on money cases in this paper.

3. You have heard from Justice Gordon about the role of equity in family law in Australia. There seems to be fraternal cohabitation here. By contrast, in England and Wales, although it is never explicitly spelt out, the implication is that we are generally incapable of dealing with proper law.

The cult of the silo, or desert island syndrome, or sanctuary in Alsatia

4. However, we are never going to escape from this image for as long as we, to mix metaphors, make rods for our own backs and give our critics an open goal. We do so by sporadically adopting different trial procedures, and rules of evidence, and occasionally even rules of substantive law, to those prescribed by the general law. So powerful is the allure of this exceptionalism that it at times appears to acquire the attributes of a cult. It exists in spite of a policy to try to have the Family Procedure Rules mirror the Civil Procedure Rules as closely as possible. See MG v AR [2021] EWHC 3063 (Fam) at [8]:

“An underpinning principle of the Family Procedure Rules is that, wherever possible, they should, if not mirror, then certainly be aligned with the CPR when covering the same procedural terrain. This is vital in order to allay concerns that family law, and those who practise and administer it, occupy some kind of desert island or legal Alsatia.”3

5. Sir James Munby was, and remains, a stalwart toiler in the vineyard of universal orthodoxy. He abhorred the cult of the family law silo. For him, family law was a piece of the continent, a part of the main. I have recently taken up the baton. I hope you will forgive me citing some of my own decisions in defence of our rightful place at the heart of the legal world.

6. Let us look at some examples of the cult of the silo.

7. In Richardson v Richardson [2011] EWCA Civ 79, [2011] 2 FLR 244, there was an issue whether the husband should be fixed under agency law with constructive knowledge of certain events. Munby LJ held at [53]:

“The Family Division is part of the High Court. It is not some legal Alsatia where the common law and equity do not apply. The rules of agency apply there as much as elsewhere. But in applying those rules one must have regard to the context, and the relevant context here is the law of ancillary relief and, more particularly, as Mr Dyer has correctly said, the rules which apply where the question is whether an ancillary relief order should be set aside as between the husband and the wife's estate. And in that context the relevant legal principles are those to be found in the authorities to which I have referred. Someone in the husband's position is to be treated as knowing what, with the exercise of due diligence, he would have discovered. But in this context there is not to be imputed to him something of which he was entirely unaware merely because it was within the knowledge of an agent or employee.”4

And so Alsatia sprang into our consciences.

8. In Prest v Petrodel Resources Ltd and others [2013] UKSC 34, [2013] 2 AC 415 the Supreme Court was faced with some sloppy dicta (including, I am ashamed to say, from me) that suggested that in matrimonial proceedings the corporate veil could be pierced absent a finding of impropriety. At [23] Lord Sumption explained:

“But for much of this period, the Family Division pursued an independent line, essentially for reasons of policy arising from its concern to make effective its statutory jurisdiction to distribute the property of the marriage upon a divorce. In Nicholas v Nicholas [1984] FLR 285, the Court of Appeal (Cumming-Bruce and Dillon LJJ) overturned the decision of the judge to order the husband to procure the transfer to the wife of a property belonging to a company in which he held a 71% shareholding, the other 29% being held by his business associates. However, both members of the court suggested, obiter, that the result might have been different had it not been for the position of the minority shareholders. Cumming-Bruce LJ (at p 287) thought that, in that situation, ‘the court does and will pierce the corporate veil and make an order which has the same effect as an order that would be made if the property was vested in the majority shareholder.’ Dillon LJ said (at p 292) that ‘if the company was a one-man company and the alter ego of the husband, I would have no difficulty in holding that there was power to order a transfer of the property.’ These dicta were subsequently applied by judges of the Family Division dealing with claims for ancillary financial relief, who regularly made orders awarding to parties to the marriage assets vested in companies of which one of them was the sole shareholder. Connell J made such an order in Green v Green [1993] 1 FLR 326. In Mubarak v Mubarak [2001] 1 FLR 673, 682C, Bodey J held that for the purpose of claims to ancillary financial relief the Family Division would lift the corporate veil not only where the company was a sham but ‘when it is just and necessary’, the very proposition that the Court of Appeal had rejected as a statement of the general law in Adams v Cape Industries. And in Kremen v Agrest (No 2) [2011] 2 FLR 490, para 46, Mostyn J held that there was a ‘strong practical reason why the cloak should be penetrable even absent a finding of wrongdoing.’”

9. Of course, it was an entirely needless derogation which was always bound to be shot down, as the relevant impropriety can invariably be found, on the facts, to exist.

10. So it was hardly surprising that Lord Sumption JSC observed at [37] that

“Courts exercising family jurisdiction do not occupy a desert island in which general legal concepts are suspended or mean something different.”

The idea of the desert island was thus born.

11. In Kerman v Akhmedova [2018] EWCA Civ 307, [2018] 2 FLR 354, the husband’s solicitor had been brought before the court on a witness summons to give evidence about the husband’s means in circumstances where the husband was not engaging in the proceedings and was taking every step to frustrate the wife’s legitimate claim. On the solicitor’s appeal it was argued that Haddon-Cave J had permitted procedures to be adopted that were "inappropriate and disproportionate and which should not be permitted to stand as a precedent." Of Haddon-Cave J's handling of the substantive financial remedy proceedings it was asserted that "all proper judicial restraint seems to have been abandoned." It was argued that to dismiss Mr Kerman's appeal would be to "sanction the adopting of procedures in the Family Division that go far beyond anything that the High Court and public policy has considered permissible to date”. These complaints were all resoundingly rejected. However, Munby P went on at [20 -22]:

“20. Mr Shepherd was … on much firmer ground when he asked rhetorically, ‘Whether the Family Court is to be permitted to adopt different trial and post trial procedures to those permitted by other divisions of the High Court.’ As a matter of generality, the answer to this is, and must be, an emphatic NO!

21. It is the best part of sixty years since Vaisey J explained in In re Hastings (No 3) [1959] Ch 368 that ‘there is now only one court – the High Court of Justice.’ It is now eleven years since I observed in A v A [2007] EWHC 99 (Fam), [2007] 2 FLR 467, paras 19, 21 (though, of course, at the time I was a mere puisne), that ‘the [Family Division cannot] simply ride roughshod over established principle’ and that ‘the relevant legal principles which have to be applied are precisely the same in this division as in the other two divisions.’ In Richardson v Richardson [2011] EWCA Civ 79, [2011] 2 FLR 244, para 53, we said that, ‘The Family Division is part of the High Court. It is not some legal Alsatia where the common law and equity do not apply.’ And in Prest v Petrodel Resources Ltd and others [2013] UKSC 34, [2013] 2 AC 415, para 37, Lord Sumption JSC observed that ‘Courts exercising family jurisdiction do not occupy a desert island in which general legal concepts are suspended or mean something different.’ …

23. It is time to give this canard its final quietus.5 Let it be said and understood, once and for all: the legal principles – whether principles of the common law or principles of equity – which have to be applied in the Family Division (and, for that matter, also, of course, in the Family Court) are precisely the same as in the Chancery Division, the Queen’s Bench Division and the County Court.”

12. In that case there had been no trip to the desert island. But the problem persists. There remains at large a view that family law has seceded from the main legal family and is, as I put it in RL v Nottinghamshire CC & Anor [2022] EWFC 13 at [41], seen as:

“a rogue castaway marooned on a desert island conducting itself without regard to the norms of the rest of the legal universe.”

13. In that case I was wrestling with a line of family authority which held that doctrine of res judicata did not apply in children’s cases. I tried to devise an interpretation of that case-law which conformed with general law principles, principles described by Lord Wilberforce as of "high public importance",6 by Lord Bridge of Harwich as being of "fundamental importance";7 and by Lord Carnwath as a "principle of general public concern."8

14. It was not a money case and so I will deal with the issue in short order.

15. We are sometimes our own worst enemies. We had rejected the general law doctrine of res judicata in children’s cases and replaced it with an alternative bespoke test. That test was stated by Jackson LJ in Re CTD (A Child: Rehearing) [2020] EWCA Civ 1316 at [4] to be that the court must find that:

“There [must be] solid grounds for believing that a rehearing will result in a different finding. Mere speculation and hope are not enough.”

16. But is that test really any different to the principle in the well-known decision of the House of Lords in Phosphate Sewage Company Limited v Molleson (1879) 4 App Cas 801? There Lord Cairns LC held that by way of exception to the rule of res judicata an anterior judgment can be challenged where additional facts had emerged which 'entirely changes the aspect of the case' and which 'could not with reasonable diligence have been ascertained before.'9

17. This led me to hold at [43]–[44]:

“43. It therefore seems to me that Jackson LJ's test of ‘there must be solid grounds for believing that the earlier findings require revisiting’, ought to be interpreted conformably with these exceptions if a divergence from the general law is to be averted. This would mean that ‘solid grounds’ would normally only be capable of being shown in special circumstances where new evidence had emerged which entirely changes the aspect of the case and which could not with reasonable diligence have been ascertained before. Such an interpretation would also be consistent with the powerful reasoning of Waite LJ referred to above where he said that the court will in the ‘general run of children's cases’ rigorously ensure that no-one is allowed to litigate afresh issues that have already been determined. It would also chime with the alternative rule for inquisitorial proceedings proposed by Diplock LJ referred to above.

44. This interpretation would have the advantage of ensuring that family law is not seen as a rogue castaway marooned on a desert island conducting itself without regard to the norms of the rest of the legal universe. It would help to promote a perception that family law is part of, and not separate from, the general law …”

I await the verdict of the Court of Appeal.

Stop press: admissibility of a foreign conviction in a children case

18. On 5 August 2022 the decision of the Court of Appeal in Re W-A (Children: Foreign Conviction) [2022] EWCA Civ 1118 was published. This was a children case and so I will deal with it in short order.

19. You will recall the rule in the Duchess of Kingston's case [1775-1802] All ER Rep 623 (20 April 1776) where Sir William de Grey, Lord Chief Justice of the Common Pleas, stated:

“What has been said at the Bar is certainly true as a general principle, that a transaction between two parties, in judicial proceedings, ought not to be binding upon a third; for it would be unjust to bind any person who could not be admitted to make a defence, or to examine witnesses, or to appeal from a judgment he might think erroneous. Therefore, the depositions of witnesses in another cause in proof of a fact, the verdict of a jury finding the fact, and the judgment of the court upon facts found, although evidence against the parties, and all claiming under them, are not, in general, to be used to the prejudice of strangers.”

20. This rule was given modern expression in Hollington v Hewthorn [1943] KB 587 by Goddard LJ. In that personal injury action a conviction for careless driving by the defendant was held to be inadmissible. Goddard LJ held:

“Assume that evidence is called to prove that the defendant did collide with the plaintiff, that has only an evidential value on the issue whether the defendant, by driving carelessly, caused damage to the plaintiff. To link up or identify the careless driving with the accident, it would be necessary in most cases, probably in all, to call substantially the same evidence before the court trying the claim for personal injuries, and so proof of the conviction by itself would amount to no more than proof that the criminal court came to the conclusion that the defendant was guilty. It is admitted that the conviction is in no sense an estoppel, but only evidence to which the court or a jury can attach such weight as they think proper, but it is obvious that once the defendant challenges the propriety of the conviction the court, on the subsequent trial, would have to retry the criminal case to find out what weight ought to be attached to the result. It frequently happens that a bystander has a complete and full view of an accident. It is beyond question that, while he may inform the court of everything that he saw, he may not express any opinion on whether either or both of the parties were negligent. The reason commonly assigned is that this is the precise question the court has to decide, but, in truth, it is because his opinion is not relevant. Any fact that he can prove is relevant, but his opinion is not. The well recognized exception in the case of scientific or expert witnesses depends on considerations which, for present purposes, are immaterial. So, on the trial of the issue in the civil court, the opinion of the criminal court is equally irrelevant.”

21. The correctness of that decision was doubted. In Hunter v Chief Constable of West Midlands [1982] AC 529 at 543 Lord Diplock said that it "is generally considered to have been wrongly decided".

22. In any event the tendency of modern procedural law is to eschew rules excluding certain types of evidence. The abolition of the rule against hearsay in all civil proceedings by the Civil Evidence Act 1995 is a classic example. In Rogers & Anor v Hoyle [2013] EWHC 1409 (QB) Leggatt J stated at [27]:

“The tendency of the law has been and continues to be towards the abolition of such rules. The modern approach is that judges (and, increasingly, juries) can be trusted to evaluate evidence in a rational manner, and that the ability of tribunals to find the true facts will be hindered and not helped if they are prevented from taking relevant evidence into account by exclusionary rules.”

23. The actual decision in Hollington was reversed by s. 11 of the Civil Evidence Act 1968 which provided that in any civil proceedings the fact that a person has been convicted of an offence by any court in the United Kingdom shall be admissible for the purpose of proving that he committed that offence, unless the contrary is proved. However, in the report of the Law Reform Committee (the predecessor of the Law Commission) which led to that legislation, it was specifically stated that it did not recommend the abolition of the rule in relation to foreign convictions. And in in Hoyle v Rogers & Anor [2014] EWCA Civ 257 Christopher Clarke LJ held at [39] that the rule survived. He reasoned that the rule lived on because:

"The trial judge must decide the case for himself on the evidence that he receives, and in the light of the submissions on that evidence made to him. To admit evidence of the findings of fact of another person, however distinguished, and however thorough and competent his examination of the issues may have been, risks the decision being made, at least in part, on evidence other than that which the trial judge has heard and in reliance on the opinion of someone who is neither the relevant decision maker nor an expert in any relevant discipline, of which decision making is not one. The opinion of someone who is not the trial judge is, therefore, as a matter of law, irrelevant and not one to which he ought to have regard."

24. In mainstream civil proceedings it would therefore seem that an anterior domestic or foreign judgment between different parties remains inadmissible unless it is a domestic (but not a foreign) criminal conviction. Of course, this rule does not prevent the terms of an anterior judgment being the very reason why the current proceedings should be stopped as an abuse of the court’s process (Hunter v Chief Constable of the West Midlands Police [1982] AC).

25. Re W-A (Children: Foreign Conviction) [2022] EWCA Civ 1118 concerned care proceedings where the mother’s husband (“H”) had a conviction in Spain for sexual offences against a child. Lieven J held that it was admissible and had presumptive weight i.e. that it should be treated in the same way as a domestic conviction under s.11 of the 1968 Act. She observed that it would be absurd if it were otherwise in circumstances where H was, by virtue of the Sexual Offences Act 2003, a registered sex offender. His offences are recorded on the Police National Computer. He had been convicted in England for the breach of a notification requirement arising from his foreign conviction.

26. Jackson LJ had little difficulty in deciding that the conviction was admissible and had presumptive weight. He gave an extensive judgment in which he stated at [7] that “financial remedy proceedings are …beyond the scope of this judgment”. The judgment was confined to “family proceedings” defined by him as a public law children case under Part IV of the Children Act 1989, a private law children case under Part I, a case under the inherent jurisdiction of the High Court relating to children, and a welfare case under the Mental Capacity Act 2005.

27. His essential reasoning was that family proceedings were different to mainstream civil proceedings:

“13. Family proceedings involve a fact-finding element, on the basis of which assessments and decisions are made. In care proceedings, proof of the significant harm threshold is a precondition for the court to exercise its powers and it has been said that, while the proceedings overall are essentially inquisitorial, they are necessarily adversarial in that respect… However, the fact-finding element of the process cannot be isolated from the welfare decision it informs. In this respect the position differs from other kinds of civil proceedings, as reflected in the respective procedural rules. The overriding objective under the Civil Procedure Rules is to enable the court to deal with cases justly and at proportionate cost, while under the Family Procedure Rules it is to enable the court to deal with cases justly, having regard to any welfare issues involved.

14. The characteristics of family proceedings therefore speak strongly against the existence of artificial evidential constraints that may defeat the purpose of the jurisdiction. …

20. As matter of principle, I would therefore hold that the criminal conviction is plainly relevant evidence that is admissible in the care proceedings. I turn to consider whether we are bound by authority to reach a different conclusion. I can immediately say that in my view we are not. As I have explained, the rules of evidence in family proceedings are different to those in other kinds of civil proceedings because the rights and interests at stake are different. It might be said that family proceedings represent an exception to the rules of admissibility that apply in civil proceedings, but the better analysis is that the purpose of rules of evidence is to achieve justice, not injustice, and that strict evidentiary rules such as res inter alios acta, estoppel and the rule in Hollington v Hewthorn have never applied in this welfare-based jurisdiction. …

35. In my view descriptions of the ratio decidendi of Hollington v Hewthorn rather depend upon the degree of generality with which the question is approached and the nature of the case in which the question is being asked. It can be argued, as the judge did here, that the rule cannot apply where it is possible to know what the earlier decision proved because the issues are identical, and when it would not cause unfair prejudice to third parties to admit the earlier decision. If it was necessary to do so, I might be prepared to distinguish Hollington v Hewthorne on that basis, but the distinction may not hold in other cases. In the end the fundamental point is that the rule does not apply at all to the type of proceedings with which we are concerned. …

50. The rule in Hollington v Hewthorn does not apply in family proceedings as I have defined them because such a rule is incompatible with the welfare-based and protective character of the proceedings.

51. In family proceedings all relevant evidence is admissible. Where previous judicial findings or convictions, whether domestic or foreign, are relevant to a person's suitability to care for children or some other issue in the case, the court may admit them in evidence. …

53. In this case the judge was right to find that the conviction of MH is plainly relevant evidence in these proceedings and that there is no rule of evidence that makes it inadmissible. As Leggatt J said in the civil context of Rogers v Hoyle at [27], the modern approach is that judges can be trusted to evaluate evidence in a rational manner, and that the ability of tribunals to find the true facts will be hindered and not helped if they are prevented from taking relevant evidence into account by exclusionary rules. This is all the more so in family proceedings, where exclusionary rules such as estoppel, res inter alios acta and Hollington v Hewthorn do not apply because they would not serve the interests of children and their families or the interests of justice.

54. As I have said, while it might be possible to distinguish the present case from Hollington v Hewthorn on the basis of identity of issues and lack of unfairness to third parties, it is unnecessary to found the analysis on these narrower and more contestable matters that depend on identifying the true ratio of the decision. Nor do I attach special significance to the inquisitorial nature of the proceedings. The important consideration is not that family proceedings are inquisitorial in form but that they are welfare-based in substance**.”

28. In my opinion it is regrettable that the obvious non-application of the rule in that case was justified by reference to the mantra that the “general law does not apply to us”. An exception to the rule could have been very easily derived from the general law, namely that (a) the proceedings were inquisitorial in nature and this exclusionary rule cannot co-exist with the inquisitorial duty of the court, (b) the issues were the same namely whether H had sexually abused children in the past, and (c) no “strangers” would be prejudiced. Indeed Jackson LJ showed in [54] precisely how the rule could be disapplied under the general law.

29. The judgment of Bean LJ demonstrates how straightforward it would have been to have derived an exception under the general law to the rule:

“61. As to the point of principle, no one in this case has argued that MH's conviction in Spain should be conclusive. But the suggestion that it should not even be admissible is alarming. It is not difficult to imagine a care case in which a relevant party has been convicted of a serious sexual or violent offence in a foreign court, but the English court has no independent evidence of the facts on which the conviction was based. It cannot be right that in such a case the family court in England and Wales deciding issues relating to the welfare of children should have to ignore the conviction and somehow pretend that the relevant party is of entirely good character and that the offences of which he was convicted never happened.”

30. In my humble opinion we will always be regarded as the poor relation for as long as we persist in a vision of ourselves as practitioners of a mystical separate art.

31. It is reasonable to conclude that: “Le canard n'a pas été terminé. Cela vit.”

And the high priests of exceptionalism would no doubt add:

“Vive le canard!”

Two fundamental differences to mainstream civil proceedings

32. While I am the strongest champion of the family law judiciary and practitioners, I do remain concerned that we will often be regarded as the poor relation for two reasons. First, there is the problem, which is not present in Australia, that the very foundation of the legal principles underpinning our financial remedy law have been proclaimed from the summit to be at variance to those supplied by equitable or proprietary principles. There is nothing anyone can do about that. We have been there before. Prior to 1858 family law was practised and determined largely in the Ecclesiastical Court, which had an entirely different set of procedural and substantive law rules (being based on Roman Law). The system was staffed by its own exotic practitioners, the doctors, who spoke their own language. In his third book “Nothing but the Truth” the Secret Barrister has said that for a lay person watching an English court case is like watching a performance of a play by Berthold Brecht to a room full of dachshunds. That is exactly what a visit to the Ecclesiastical Court must have seemed before 1858, and certainly what a visit to a financial remedy court, using its own exotic language and applying Lord Nicholls’ substantive law rules, must look like now.

33. So that is the first big difference.

34. Second, as I will explain, the most egregious example of rogue castaway syndrome is our judge-made practice of hearing all money cases behind closed doors; of publishing the judgments anonymously; and of imposing a perpetual mantle of inviolable secrecy over the proceedings and the judgment.

35. Reverting to the first reason, I am aware that the High Court of Australia has held in Stanford v Stanford [2012] HCA 52 that:

“37. First, it is necessary to begin consideration of whether it is just and equitable to make a property settlement order by identifying, according to ordinary common law and equitable principles, the existing legal and equitable interests of the parties in the property. …

38. Second, although s 79 confers a broad power on a court exercising jurisdiction under the Act to make a property settlement order, it is not a power that is to be exercised according to an unguided judicial discretion. In Wirth v Wirth, Dixon CJ observed that a power to make such order with respect to property and costs ‘as [the judge] thinks fit’, in any question between husband and wife as to the title to or possession of property, is a power which ‘rests upon the law and not upon judicial discretion’. …

39. Because the power to make a property settlement order is not to be exercised in an unprincipled fashion, whether it is ‘just and equitable’ to make the order is not to be answered by assuming that the parties' rights to or interests in marital property are or should be different from those that then exist. All the more is that so when it is recognised that s 79 of the Act must be applied keeping in mind that ‘[c]ommunity of ownership arising from marriage has no place in the common law’. Questions between husband and wife about the ownership of property that may be then, or may have been in the past, enjoyed in common are to be ‘decided according to the same scheme of legal titles and equitable principles as govern the rights of any two persons who are not spouses’. The question presented by s 79 is whether those rights and interests should be altered …

40. Third, whether making a property settlement order is ‘just and equitable’ is not to be answered by beginning from the assumption that one or other party has the right to have the property of the parties divided between them or has the right to an interest in marital property which is fixed by reference to the various matters (including financial and other contributions) set out in s 79(4). The power to make a property settlement order must be exercised ‘in accordance with legal principles, including the principles which the Act itself lays down’. To conclude that making an order is ‘just and equitable’ only because of and by reference to various matters in s 79(4), without a separate consideration of s 79(2), would be to conflate the statutory requirements and ignore the principles laid down by the Act” (emphasis added)

36. As I understand it, the effect of this decision is that the court must start with the proprietary positions of the parties as determined by law and equity and will only adjust those positions inasmuch as justice demands an adjustment.

37. This, of course, embeds your property settlement law firmly in the mainstream of the general law.

La révolution de 5 Brumaire CCIX (Cinquième Brumaire An Deux Cent Neuf)10

38. What is very interesting is that this decision by your top court was only two years after the canonical decision of White v. White [2000] UKHL 54 [2001] 1 AC 596 was handed down by the House of Lords. As is well known, in that case Lord Nicholls, the foremost Chancery Judge of the modern era, decided, we speculate over boiled eggs at breakfast, completely to upend the established order which had ordained for decades that the wife’s claim would be met by reference to her reasonable requirements and nothing more.

39. In the Court of Appeal in that case the judges had expressed concern at the obvious inherent unfairness of the established order. At first instance the wife’s proprietary position was about £1.4 million but her needs were only £984,000. Holman J strictly applied the governing orthodoxy: his order had the effect of requiring Mrs White to pay Mr White £400,000. Thorpe LJ held:

“Although there is no ranking of the criteria to be found in the statute, there is as it were a magnetism that draws the individual case to attach to one, two, or several factors as having decisive influence on its determination. The proposition is almost too obvious to require examples from the decided cases. That said there is, if not a priority, certainly a particular importance attaching to section 25(2)(a). First in almost every case it is logically necessary to determine what is available before considering how it should be allocated and it is natural that the draughtsman should have commenced his check list with that first step. There is another reason in my judgment why practitioners and judges should first have regard to ‘the income, earning capacity, property and other financial resources which each of the parties to the marriage has or is likely to have in the foreseeable future’. Contested ancillary relief proceedings are invariably stressful and costly. For any family they should be a last resort. In H v H (Financial Provision: Capital Allowance) [1993] 2 FLR 335 at 347 I expressed my opinion that the discretionary powers of the court to adjust capital shares between spouses should not be exercised unless there is a manifest need for intervention upon the application of the section 25 criteria. Where the parties have during marriage elected for a financial regime that makes each financially independent one gain might be said to be that they may thereby have obviated the need to embark upon ancillary relief litigation in the event of divorce.”

40. Had this remained the governing principle then one can conjecture that our law and yours would have developed along parallel paths. But in the House of Lords, Lord Nicholls disagreed and held:

“47. [Mr White’s] next criticism was that the members of the Court of Appeal placed undue emphasis on the financial worth of each party on the dissolution of the partnership. This was a wrong approach, as was the view that the court should not exercise its statutory powers unless there was a 'manifest case for intervention'. I agree that both Thorpe LJ and Butler-Sloss LJ did attach considerable importance to the wife's entitlement under the partnership. There are observations, particularly in the judgment of Thorpe LJ, which, read by themselves, might suggest that in this regard the clock was being turned back to the pre-1970 position. Then courts often had to attempt to unravel years of matrimonial finances and reach firm conclusions on who owned precisely what and in what shares. The need for this type of investigation was swept away in 1970 when the new legislation gave the court its panoply of wide discretionary powers. Since then, the courts have not countenanced parties incurring costs which would be disproportionate to the assistance the expenditure would give in carrying out the section 25 exercise.

48. All this is well established. So much so, that I cannot believe that either Thorpe LJ or Butler-Sloss LJ intended to gainsay this approach. Indeed, Butler-Sloss LJ stated expressly that what she had in mind, where parties were in business together, was a broad assessment of the financial position and not a detailed partnership account. She rightly noted that, even in such a case, the parties' proprietorial interests should not be allowed to dominate the picture: see [1999] 2 WLR 1213, 1227. If Thorpe LJ went further than this, he went too far.”

41. Instead, Lord Nicholls went on to deliver his famous pronouncements. It was the family law equivalent of Moses bearing the tablets down from Mount Sinai:

“25. … As a general guide, equality should be departed from only if, and to the extent that, there is good reason for doing so. The need to consider and articulate reasons for departing from equality would help the parties and the court to focus on the need to ensure the absence of discrimination. …

35. … If a husband and wife by their joint efforts over many years, his directly in his business and hers indirectly at home, have built up a valuable business from scratch, why should the claimant wife be confined to the court's assessment of her reasonable requirements, and the husband left with a much larger share? Or, to put the question differently, in such a case, where the assets exceed the financial needs of both parties, why should the surplus belong solely to the husband? On the facts of a particular case there may be a good reason why the wife should be confined to her needs and the husband left with the much larger balance. But the mere absence of financial need cannot, by itself, be a sufficient reason. If it were, discrimination would be creeping in by the back door. In these cases, it should be remembered, the claimant is usually the wife. Hence the importance of the check against the yardstick of equal division. …

42. This distinction is a recognition of the view, widely but not universally held, that property owned by one spouse before the marriage, and inherited property whenever acquired, stand on a different footing from what may be loosely called matrimonial property. According to this view, on a breakdown of the marriage these two classes of property should not necessarily be treated in the same way. Property acquired before marriage and inherited property acquired during marriage come from a source wholly external to the marriage. In fairness, where this property still exists, the spouse to whom it was given should be allowed to keep it. Conversely, the other spouse has a weaker claim to such property than he or she may have regarding matrimonial property.”

42. This is a world away from Stanford. I would be interested to know if White was cited to the High Court.

43. White has revolutionised our property settlement law. Its principles were emphatically reaffirmed by the House of Lords in Miller v Miller [2006] UKHL 24, [2006] 2 AC 618. The pace of change since has been extraordinary. Boissy d’Anglas, the French statesman, famously observed that from the vantage-point of 1795 it seemed that French men and women had lived six centuries in the space of six years. So it has seemed in the financial remedy world following Lord Nicholls’s revolution of 5 Brumaire CCIX. Where we end up is anyone’s guess. In 1971 Zhou Enlai (Prime Minister under Mao Zedong) was asked what in his opinion were the main influences and consequences of the French Revolution. His reply was that it was “too early to say”. 22 years after White I would say that the same about the revolution of 5 Brumaire.

44. It has been described as a judge-made regime of deferred community of matrimonial property. Basically, whether the marriage is long or short, childless or child-full, the acquest will, subject to the meeting of needs, be divided equally.

45. I am a strong believer in the justice of this approach. It is very easy for litigants to understand and accept as fair and just a decision that the assets generated during the marriage should be divided equally. It is very difficult for litigants to understand why they should be divided 60:40. An explanation that the reason for the unequal division is because the contributions of one party (usually the man) were judged to be of greater value than those of the other party (usually the woman) tends to be met with total incomprehension. And it is very often difficult to explain why that is not blatant discrimination.

46. This is why I have always endeavoured to arrive at a figure for divisible matrimonial property which will be shared equally. True, the process of arriving at that figure for divisible matrimonial property may, sometimes, appear to be contrived. This takes us to Procrustes and his bed.

47. In WM v HM [2017] EWFC 25 (otherwise Martin)** I held:

"38. I am firmly of the view that the correct approach to give effect to the sharing principle is to try to calculate the scale of the matrimonial property and then normally to share that equally leaving the non-matrimonial property untouched. This is logically pure, morally sound, easy to understand, and limits individual judicial caprice. I recognise that not everyone agrees with this approach. For example, the Hong Kong Court of Appeal in AVT v VNT (CACV 234/2014) at para 69 described it as ‘not helpful at all’ apparently because it encroaches on the exercise of a wide discretion. Even so, I continue to oppose the school of thought that plucks a random percentage out of the air where the pool of assets is a mixture of matrimonial and non-matrimonial property.

39. The (equal) sharing (of matrimonial property) principle is not a Procrustean bed. Cases have shown how it has been modified (some might say manipulated) to achieve an overall intuitively fair result. Thus it has been described as a tool and not a rule. So, by way of example, Mrs Miller did not receive half of the value of Mr Miller's New Star shares, as the House of Lords felt that he had brought into the marriage some intangible unquantifiable knowhow which contributed to the later establishment of the business during the marriage. Similarly, Mrs Robertson did not receive half of the increase in value of Mr Robertson's ASOS shares, Mr Justice Holman considering that the numerically quantified figure for the value of those shares at the start just did not fairly reflect what Mr Robertson really brought into the marriage. Equivalently, Mr Jones succeeded in persuading Lord Justice Wilson to adopt a very creative, arguably artificial, inflation of the actual starting figure for the value of his business in order to shrink the amount of the matrimonial property. But in all of these cases there was fidelity to the basic principle, more or less."

My disavowal of the practices of Procrustes was not perhaps very sincere. The truth is that those us who have wholeheartedly embraced the yardstick of equality do sometimes shrink the matrimonial property so that half of it gives what we feel is the right result. Shrink factors are pre-marital value and post separation endeavour.

48. Nevertheless, it would have been very difficult for Mrs Martin to have argued that she had been a victim of discrimination because I had overvalued the business at the time of the commencement of their relationship. By contrast, if I had given her 40% because her contributions were in my judgment less valuable that Mr Martin’s then her claim would have been unassailable.

The Big Money Premiership

49. However, the inbuilt judicial fractional default seems to be 40%. This takes me to the Big Money Premiership.

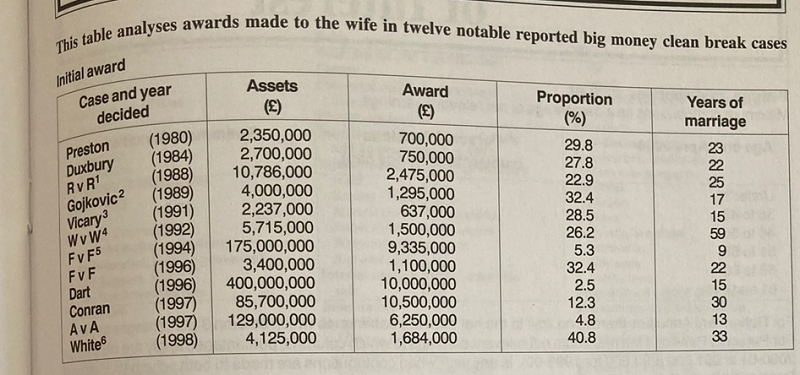

50. Before I put up the current table I show you a table published in At A Glance in January 2000, immediately before the revolution of 5 Brumaire CCIX.

Inflation since January 2000 has been 69.4%. The highest award made was to Lady Conran. It would correspond in the coin of today to a mere £17,787,204. It was a miserable 12.3% after 30 years of marriage. Perhaps you can now see why Boissy d’Anglas’s aphorism is so true.

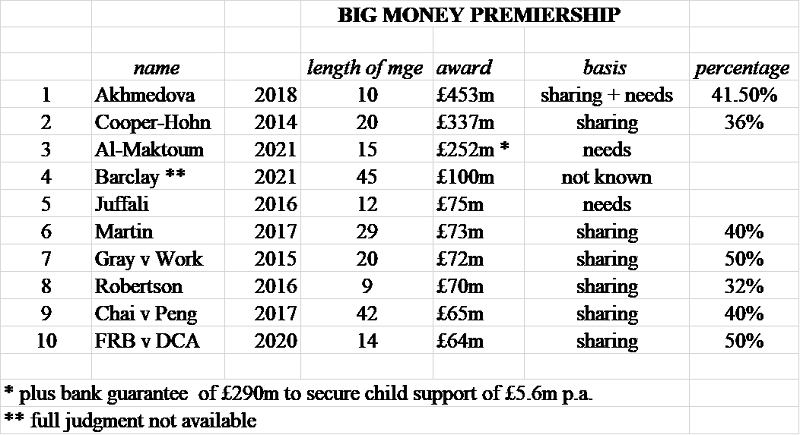

51. So, to the Big Money Premiership

52. I make a number of points:

i) In the seven sharing cases the judges found a reason not to give the wife 50% in five;

ii) In only one, Cooper-Hohn, was the doctrine of special contribution relied on. It is now consigned to history and rightly condemned as an Orwellian oxymoron;

iii) In Akhmedova, W did not ask for more than 41.5%. H did not engage and described the judgment as ‘toilet paper’. Following protracted enforcement proceedings, W, according to press reports, ultimately settled for £150m;

iv) In Martin and Robertson, there were pre-marital assets, and the judges valued that element much higher than the figures given by the respective joint experts;

v) In Chai the discount was justified by reference to illiquidity and the wife getting plums (cash) leaving the husband with duff. Query whether there was double discounting – the valuation of the “duff” business assets should capture all foreseeable risks.

vi) A list of the publicly available judgments given in the case of Al-Maktoum is in Appendix III.

Open justice

53. You will have noticed that all of these cases (bar one) are non-anonymized. Time does not permit a detailed exposition of the (near) wars of religion ignited by me in my decision of Xanthopoulos v Rakshina [2022] EWFC 30, followed by Gallagher v Gallagher (No.1) (Reporting Restrictions) [2022] EWFC 52. Suffice to say that a very bad example of desert island syndrome is the judge-made rule prohibiting journalists who are entitled to attend hearings in “chambers” or in “private” from reporting anything about the case. Equally bad is the judicial practice of publishing money judgments anonymously and of imposing perpetual secrecy over every such case.

54. I know that I must tread carefully, given the terms of your sec 121. But section 121 was a specific piece of legislation, introduced, debated, voted on and enacted. It is a paradigm example of how the issue of transparency should be democratically addressed.

55. I have set out the details in Appendix II. Unlike your law, ours is an unedifying, contradictory, mess. I give you two vignettes:

Scott v Scott [1912] P 241 per Fletcher Moulton LJ in the Court of Appeal:

“I cannot forbear adding that in my opinion nothing would be more detrimental to the administration of justice in any country than to entrust the judges with the power of covering the proceedings before them with the mantle of inviolable secrecy.”

[1913] AC 417, per Lord Shaw of Dunfermline in the House of Lords:

“If the judgments, first, declaring that the Cause should be heard in camera, and, secondly, finding Mrs. Scott guilty of contempt, were to stand, then an easy way would be open for judges to remove their proceedings from the light and to silence for ever the voice of the critic, and hide the knowledge of the truth. Such an impairment of right would be intolerable in a free country, and I do not think it has any warrant in our law. Had this occurred in France, I suppose Frenchmen would have said that the age of Louis Quatorze and the practice of lettres de cachet had returned.”

56. I have been interested to see that Lord Sumption favours secrecy over openness for family proceedings and judgments. In a recent interview for the Financial Remedies Journal he was asked and replied:

“Q: Turning to your involvement with the media, the Family Court is currently wrestling with this issue. The President has recently published guidance for opening up the family court allowing the press to actually report instead of attend. Given your recent experience with the media and some of the controversies which have arisen, are you a proponent of greater openness?

A: In principle, yes, but I think special considerations apply to family law. The proceedings of the courts are part of the public business of the state and unless there are compelling considerations of justice or national security I would in general think they should be open. I am the author of at least two judgments to broadly that effect. There are, however, some rather special considerations in family cases, and I actually think that the family courts are probably too open. There was a time when family proceedings were with minor exceptions closed to the public. Family cases normally deal with intense personal tragedies involving quite ordinary citizens. I think that the public does not have a right to know about the internal distresses in a family relationship. The public does not acquire the right to know simply because the family in question is unable to sort out the problem for itself so that the court becomes involved. So, I would make this an exception to the principle that courts transact the public business of the state. Family courts are concerned with sorting out some of the most intimate and emotional issues that an ordinary human being can experience. I regard them as providing a supporting service rather than an adjudicatory service in the sense in which one might use that word in other kinds of case.

Q: Would that also apply when it is a family against the state, for example in care proceedings?

A: Yes, for exactly the same reasons. Care proceedings are cases in which the relationship between a parent and child has in some way gone badly awry. I would not distinguish between that kind of issue and an issue between husband and wife.”

57. To say that I was surprised by this would be an understatement. It may be true, in relation to disputes about children, that “family courts are concerned with sorting out some of the most intimate and emotional issues that an ordinary human being can experience” and, therefore, the process could be seen as providing a supporting service rather than an adjudicatory service. But that is hardly true about a money case. There the issues and processes are the same as apply whenever a suitor asserts a right and claims a remedy. In Gallagher No.1 at [65] I stated:

“I accept that the husband's (ECHR) Article 8 rights would be engaged by a news report which referred to information compulsorily disclosed by him in financial remedy proceedings. However, in performing the balancing exercise I do not accept that the evidence given by former spouses in financial remedy proceedings, or the compulsion that is applied in its extraction, is either qualitatively or quantitatively different to that in most other forms of civil litigation. In my opinion the evidence about the financial history of a marital relationship adduced in financial remedy proceedings will often be less extensive, personal and detailed than the evidence given about a non-marital relationship in a Trusts of Land and Appointment of Trustees Act 1996 case or in a marital or non-marital case under the Inheritance (Provision for Family and Dependants) Act 1975. Disclosure of documents in such proceedings is made under compulsion. Yet those proceedings are heard in open court without reporting restrictions.”

58. It is the acutest irony, to put it mildly, that the Christopher Columbus of the family law desert island and the sternest critic of those family judges who have settled on it, should be in favour of the whole family judiciary chartering a ship and sailing there to avoid the ‘general legal concept’ of open justice.

Conclusion on our skills

59. I want to revert to my primary proposition. I have shown that in financial remedy cases the substantive law is neither purely statutory nor driven by equitable or proprietary principles, but is rather a unique judge-made system of deferred community of property. I have also conceded that in some procedural or evidential instances, mainly in cases about children, there is a tendency to head for the desert island. I have also explained in Appendix II that the principle of open justice has been nullified by the judges in conflict with two decisions of the House of Lords and two Acts of Parliament.

60. The controversies over open justice aside, I maintain trenchantly that the quality of legal and forensic work done by the practitioners and judges on these vast and complex cases demonstrates that we are not the poor relations, and neither are we ‘separate but equal’ members of the legal world. Rather, we are skilled mainstream players dealing with some of the most difficult financial problems imaginable. We are not an island entire of itself. We are, in the words of John Donne, a piece of the continent, a part of the main.11

61. Thank you for listening to me.

Appendix I: Exorbitant costs

1. This appendix addresses the curse of excessive costs. This is a not uncommon phenomenon which besmirches the integrity of the process and sullies the reputation of the court and those who work in it.

2. There are now in place recent special measures designed to limit costs and to make litigants aware of what they are spending. These are:

i) The promulgation on 27 May 2019 of the amendment to PD 27A para 4.4, requiring open negotiations on pain of an order for costs (on which a substantial body of case law has developed). The amendment provides:

“The court will take a broad view of conduct … and will generally conclude that to refuse openly to negotiate reasonably and responsibly will amount to conduct in respect of which the court will consider making an order for costs. This includes in a ‘needs’ case where the applicant litigates unreasonably resulting in the costs incurred by each party becoming disproportionate to the award made by the court.”

ii) The promulgation on 6 July 2020 of the new FPR 9.27, PD 9A paras 3.1 3.2A, 3.2B and 3.2C and new Forms H1 and H. These require parties to state in writing at every hearing what costs they have incurred and will incur. They also require open offers to be made.

iii) The issue on 11 January 2022 of the FRC Efficiency Statement para 31 of which stipulates that position statements for each hearing must contain short details of what efforts the parties have made to negotiate openly, reasonably and responsibly. It goes on to say that the parties will be warned that, whatever the size of the case, a failure to make reasonable attempts to compromise cases in open negotiation will be met by costs penalties.

3. There are no equivalent measures in the civil sphere where cases take forever and where costs can outweigh the value of the claim.

4. But these measures notwithstanding there are still too many cases where the parties appear hell-bent on Wagnerian immolation. Peel J has turned into a tremendous wordsmith, recently condemning an couple who had fought themselves to a standstill for their “nihilistic” litigation. In a recent case12 Judge Wildblood QC lambasted a couple for their ‘feral, unprincipled and unnecessarily expensive financial remedy proceedings’ and concluded at para 200:

“As I have made plain throughout this judgment, I consider that these proceedings are a disgraceful example of how financial remedy proceedings should not be conducted. The wife may wish to take advice about why her case was presented in this way and why so much expense has been incurred.’”

5. In Xanthopoulos v Rakshina at [11]–[14] I said:

“11. Thus, we are looking at the total cost of the litigation between these parties being somewhere between £7.2 million and £8 million, of which £5.4 million has already been incurred.

12. Figures like this are hard to accept even in a conflict between the uber-rich, but in this case the wife's Form E discloses two properties in London each worth about £5 million and a sum of about £11 million in the Coutts account. There are predictable disputes as to the true beneficial ownership of one of the properties and of the sum in the Coutts account. The wife also discloses properties in Siberia worth a little over £1 million. The husband, who has next to nothing in his name, says that this is an entirely false presentation and that the wife is correctly ranked by Forbes as the 75th richest woman in Russia, with vastly valuable interests in supermarkets in Siberia. Even if this were true (and the suggestion is hotly contested) to run up in domestic litigation costs of between £7 million and £8 million is beyond nihilistic. The only word I can think of to describe it is apocalyptic.

13. It is difficult to know what to say or do when confronted with such extraordinary, self-harming conduct. Periodically the judges bemoan the heedless incurring by divorcing parties of huge costs. What was regarded in 1996 as gross costs inflation was the principal driver for the ancillary relief pilot scheme of 25 July 1996: Practice Direction [1996] 2 FLR 368. In 2014 in J v J [2014] EWHC 3654 (Fam), [2016] 1 FCR 3 I exploded with indignation at the rate and scale of costs incurred in that case and solemnly pronounced that ‘something must be done’. With the benefit of hindsight those costs – a total of £920,000 – now seem almost banal. The rules have been changed so that orders have to record the costs incurred and to be incurred (see FPR 9.27(7)). Para 4.4 of FPR PD 28A has been introduced to try to force parties to negotiate openly and reasonably in order to save costs. Yet costs continue to go up and up.

14. In my opinion the Lord Chancellor should consider whether statutory measures could be introduced which limit the scale and rate of costs run up in these cases. Alternatively, the matter should be considered further by the Family Procedure Rule Committee. Either way, steps must be taken.”

6. In Gallagher v Gallagher (No.2) (Financial Remedies) [2022] EWFC 53 I recorded that in the two years since the wife's Form A the parties have incurred costs in the extraordinary amount of £1,670,380, or 5% of the total assets. I said at [12- 13]

“12. It would be no answer to the question:

How is it that these exorbitant costs have been incurred?

to respond:

‘Well, that is what the market will bear and how the parties want to spend their money is a matter for them not the business of the court’.

It is no answer because the court is bidden to do its utmost to compel litigants to conduct their cases proportionately. The court does so in the wider public interest. It is in the public interest that citizens who invoke the rule of law should have true access to justice. A putative litigant does not have true access to justice if it is unaffordable; if it is, to adapt the weary aphorism, only open to all like the Ritz Hotel. Financial remedy litigation seems to be fast heading for Ritz Hotel status – so expensive that it is only accessible by the very rich.

13. I am not going to repeat my lamentations about the exorbitance of costs which I have expressed in recent judgments. Nor am I going to repeat my cry that something must be done. In this judgment I merely record the facts and I leave it either to the Lord Chancellor, or to the Family Procedure Rule Committee, to do something about it.”

7. I genuinely do not know what the answer to this phenomenon is. It is surely not for there to be statutorily imposed fixed costs (although that is in effect what happens if you are publicly funded). This would be an unacceptable restriction of an individual’s property rights. I await an interesting discussion with you now.

Appendix II: Open justice

1. In 1913 in a case called Scott v Scott [1913] AC 417, a routine order was made that a nullity suit be heard in camera. Mrs Scott later spoke about the case and was found to be in contempt of court, it being held that she was forever injuncted to remain silent. A minority in the Court of Appeal and a unanimous judicial committee of the House of Lords were appalled and in language which is strikingly passionate and modern struck down the finding.

2. Fletcher Moulton LJ in the Court of Appeal [1912] P 241 held:

“The conception of the Court interfering with litigants otherwise than by granting the relief which it is empowered and bound to grant is wholly vicious and strikes at the foundation of the status and duties of judges. We claim and obtain obedience and respect for our office because we are nothing other than the appointed agents for enforcing upon each individual the performance of his obligations. That obedience and that respect must cease if, disregarding the difference between legislative and judicial functions, we attempt ourselves to create obligations and impose them on individuals who refuse to accept them and who have done nothing to render those obligations binding upon them against their will.

It is this which makes me take so serious a view of the present appeal. The Courts are the guardians of the liberties of the public and should be the bulwark against all encroachments on those liberties from whatsoever side they may come. It is their duty therefore to be vigilant. But they must be doubly vigilant against encroachments by the Courts themselves. In that case it is their own actions which they must bring into judgment and it is against themselves that they must protect the public. The magnitude of the danger is illustrated by the present case. The serious encroachment on personal liberty which is here proposed is not supported by a single decision. There is on record no case where the Courts have asserted a right to control the personal acts of litigants after the conclusion of the suit except to enforce the relief granted. Yet without the support of any precedent the learned judge has in this case arrogated to judges the power to do so and we are asked to support him. The nature of the encroachment emphasizes the warning. Most people feel that the unrestricted publication in newspapers of what passes at the hearing of certain types of cases is a great evil, and many proposals have been made for regulating it. But all agree that this must be done by the Legislature. The judges are not the tribunal to decide on the proper limitations of public rights. The order in the present case is an attempt to assert for judges indefinitely wide powers in this respect. Not even the strongest partisan of legislative action has ventured to propose that private communications between individuals as to that which passes at the hearing of a suit should be interfered with. This order proceeds on the basis that a judge can of his own initiative absolutely forbid them. I have here to discuss the legal justification for such a doctrine and not its expediency, but I cannot forbear adding that in my opinion nothing would be more detrimental to the administration of justice in any country than to entrust the judges with the power of covering the proceedings before them with the mantle of inviolable secrecy."

3. Lord Shaw in the House of Lords put it, if anything, even stronger:

“I candidly confess, my Lords, that the whole proceeding shocks me. I admit the embarrassment produced to the learned judge of first instance and to the majority of the Court of Appeal by the state of the decisions; but those decisions, in my humble judgment, or rather, — for it is in nearly all the instances only so, — these expressions of opinion by the way, have signified not alone an encroachment upon and suppression of private right, but the gradual invasion and undermining of constitutional security. This result, which is declared by the Courts below to have been legitimately reached under a free Constitution, is exactly the same result which would have been achieved under, and have accorded with, the genius and practice of despotism.

What has happened is a usurpation — a usurpation which could not have been allowed even as a prerogative of the Crown, and most certainly must be denied to the judges of the land. To remit the maintenance of constitutional right to the region of judicial discretion is to shift the foundations of freedom from the rock to the sand.

It is needless to quote authority on this topic from legal, philosophical, or historical writers. It moves Bentham over and over again. ‘In the darkness of secrecy, sinister interest and evil in every shape have full swing. Only in proportion as publicity has place can any of the checks applicable to judicial injustice operate. Where there is no publicity there is no justice.’ ‘Publicity is the very soul of justice. It is the keenest spur to exertion and the surest of all guards against improbity. It keeps the judge himself while trying under trial.’ ‘The security of securities is publicity.’ But amongst historians the grave and enlightened verdict of Hallam, in which he ranks the publicity of judicial proceedings even higher than the rights of Parliament as a guarantee of public security, is not likely to be forgotten: ‘Civil liberty in this kingdom has two direct guarantees; the open administration of justice according to known laws truly interpreted, and fair constructions of evidence; and the right of Parliament, without let or interruption, to inquire into, and obtain redress of, public grievances. Of these, the first is by far the most indispensable; nor can the subjects of any State be reckoned to enjoy a real freedom, where this condition is not found both in its judicial institutions and in their constant exercise.’

I myself should be very slow indeed (I shall speak of the exceptions hereafter) to throw any doubt upon this topic. The right of the citizen and the working of the Constitution in the sense which I have described have upon the whole since the fall of the Stuart dynasty received from the judiciary — and they appear to me still to demand of it — a constant and most watchful respect. There is no greater danger of usurpation than that which proceeds little by little, under cover of rules of procedure, and at the instance of judges themselves. I must say frankly that I think these encroachments have taken place by way of judicial procedure in such a way as, insensibly at first, but now culminating in this decision most sensibly, to impair the rights, safety, and freedom of the citizen and the open administration of the law. …

For the reasons which I have given, I am of opinion that the judgment of Bargrave Deane J. cannot be sustained. It was, in my opinion, an exercise of judicial power violating the freedom of Mrs. Scott in the exercise of those elementary and constitutional rights which she possessed, and in suppression of the security which by our Constitution has been found to be best guaranteed by the open administration of justice. I think, further, that the order to hear the case in camera was not only a mistake, but was beyond the judge's power; while, on the other hand, the extension of the restrictive operation of any ruling — that a case should be heard in camera — to the actions of parties, witnesses, counsel, or solicitors, in a case, after that case has come to an end, seems to me to have really nothing to do with the administration of justice. Justice has been done and its task is ended; and I know of no warrant for such an extension beyond the time when that result has been achieved. It is no longer possible to interfere with it, to impede it, to render its proceedings nugatory. To extend the powers of a judge so as to restrain or forbid a narrative of the proceedings either by speech or by writing, seems to me to be an unwarrantable stretch of judicial authority.

I may be allowed to add that I should most deeply regret if the law were other than what I have stated it to be. If the judgments, first, declaring that the Cause should be heard in camera, and, secondly, finding Mrs. Scott guilty of contempt, were to stand, then an easy way would be open for judges to remove their proceedings from the light and to silence for ever the voice of the critic, and hide the knowledge of the truth. Such an impairment of right would be intolerable in a free country, and I do not think it has any warrant in our law. Had this occurred in France, I suppose Frenchmen would have said that the age of Louis Quatorze and the practice of lettres de cachet had returned.

4. But, if the cases were heard openly, people will be deterred from pursuing just causes I hear you murmur? Lord Shaw dealt with this objection:

There remains this point. Granted that the principle of openness of justice may yield to compulsory secrecy in cases involving patrimonial interest and property, such as those affecting trade secrets, or confidential documents, may not the fear of giving evidence in public, on questions of status like the present, deter witnesses of delicate feeling from giving testimony, and rather induce the abandonment of their just right by sensitive suitors? And may not that be a sound reason for administering justice in such cases with closed doors? For otherwise justice, it is argued, would thus be in some cases defeated. My Lords, this ground is very dangerous ground. One's experience shews that the reluctance to intrude one's private affairs upon public notice induces many citizens to forgo their just claims. It is no doubt true that many of such cases might have been brought before tribunals if only the tribunals were secret. But the concession to these feelings would, in my opinion, tend to bring about those very dangers to liberty in general, and to society at large, against which publicity tends to keeps us secure: and it must further be remembered that, in questions of status, society as such — of which marriage is one of the primary institutions — has also a real and grave interest as well as have the parties to the individual cause

(Emphases added.)

5. 109 years on we find ourselves in the same heretical position. From the start of the era of secular divorce in 1858 Registrars were allowed to make some substantive ancillary relief decisions. Progressively, more and more kinds of cases would be heard by Registrars. By 1977 the default forum for all ancillary relief cases was the Registrar, although cases could and often were referred for hearing by the Judge in Court. The Registrar always sat in chambers. In the Family Proceedings Rules 1991 r.2.66(2) it was stated that hearings shall, unless the court otherwise directs, take place in chambers. In the Family Procedure Rules 2010 r.27.10 this was changed to provide that proceedings to which these rules apply will be held in private. No iteration of the Rules over 164 years says anything about the consequence, in terms of reportability, of a hearing being in chambers or in private.

6. However, the Administration of Justice Act 1960 specifically addresses the status of hearings held in private. Section 12(3) provides that hearings "in private", "in chambers" and "in camera" are treated equally. Section 12(1) lists those sensitive types of proceedings which are covered with the mantle of secrecy, breach of which is a contempt of court. Those cases are (a) where the proceedings relate to the exercise of the inherent jurisdiction of the High Court with respect to minors, or are brought under the Children Act 1989 or the Adoption and Children Act 2002 or otherwise relate wholly or mainly to the maintenance or upbringing of a minor; (b) where the proceedings are brought under the Mental Capacity Act 2005, or under any provision of the Mental Health Act 1983 authorising an application or reference to be made to the First-tier Tribunal, the Mental Health Review Tribunal for Wales or the county court; (c) where the court sits in private for reasons of national security during that part of the proceedings about which the information in question is published; (d) where the information relates to a secret process, discovery or invention which is in issue in the proceedings; (e) where the court (having power to do so) expressly prohibits the publication of all information relating to the proceedings or of information of the description which is published.

7. The list of statutes mentioned in subsection 1(a) and (b) does not include the Matrimonial Causes Act 1973. A financial remedy case which is not mainly about child maintenance is therefore not a secret proceeding under this provision, and it is not a contempt to report the details of such a case, especially where by a rule change in 2009 journalists and latterly legal bloggers have been allowed into financial remedy proceedings heard in private without any explicit prohibition on reporting what they hear.

8. It is therefore not, as such, a contempt of court (a) to publish an account of what has gone on at a hearing of a family case in private or (b) to publish a judgment in a family case delivered in private or (c) to identify the parties in an anonymised family judgment. Litigants, even in a family case heard in private, have the right to talk about the case; and a judge has no power to prevent them doing so. This is subject to any statutory provision to the contrary. The only relevant statute is the Human Rights Act 1998.

9. First, and of central importance, questions of transparency and anonymity fall to be resolved by having regard to and evaluating, in accordance with the ‘balancing exercise’ mandated by the decision of the House of Lords in In re S (a child) [2004] UKHL 47; [2005] 1 AC 593 the interests of the parties and the public as protected by Articles 6, 8 and 10 of the Convention, considered in the particular circumstances of the case.

10. More specifically, the right of litigants to speak about cases heard in private is protected by Articles 8 and 10, albeit now qualified by “the need to protect the rights of others who are participants in the ‘story’.” Indeed, “the right to tell one’s own story is likely to carry considerable weight.”

11. It is said that no one right has automatic priority over another where they are in competition in the balancing exercise

12. I therefore contend that automatic secrecy is unlawful. There must be an application for a reporting restriction order, served on the media under s 12(2). Then there must be a balancing exercise on the facts of the individual case.

13. But the debate rages on. It is virtually identical to that which the House of Lords put an emphatic end to 109 years ago.

14. Compare these two recent statements.

15. In Gallagher v Gallagher (No. 1) (Reporting Restrictions) [2022] EWFC 52 (13 June 2022) at [72] I said:

“The resistance to letting sunlight into the Family Court seems to be an almost ineradicable adherence to what I would describe as desert island syndrome, where the rules about open justice operating in the rest of the legal universe just do not apply because ‘we have always done it this way’. In my judgment the mantra ‘we have always done it this way’ cannot act to create a mantle of inviolable secrecy over financial remedy proceedings which the law, as properly understood, does not otherwise recognise. I do acknowledge, however, that the tenacity of desert island syndrome is astonishing. Notwithstanding the passion and erudition with which Fletcher Moulton LJ, Earl Loreburn, Lord Atkinson and Lord Shaw wrote 109 years ago to eliminate it, it is with us still.”

16. Contrast this to Moor J in IR v OR [2022] EWFC 20 (29 March 2022) at [29]:

“[The Husband] complains that the Wife has threatened him with publicity if the case proceeds. I believe this refers to proposed changes to the rules on anonymity in financial remedy proceedings but they are not in place yet. I am clear that, until I am told I have to permit publication, litigants are entitled to their privacy in the absence of special circumstances, such as where they have already courted publicity for the proceedings which is not the case here.”

17. To achieve that he anonymised and published his judgment with a standard rubric:

“The judgment was delivered in private. The judge has given leave for this version of the judgment to be published. The parties and their children may not be identified by name or location. The anonymity of everyone other than the lawyers and anyone else specifically named in this version of the judgment must be strictly preserved. All persons, including representatives of the media, must ensure that this condition is strictly complied with. Failure to do so will be a contempt of court.”

I draw attention to the lack of any time limit on these prohibitions.

18. To add to the controversy, in Xanthopoulos v Rakshina [2022] EWFC 30 (12 April 2022) at [76] et seq I had said that this standard rubric was not worth the paper it was written on. It is not an injunction: there was no application for an injunction; no service of an application notice; no order was issued; and no order was served endorsed with a penal notice. There is no statute that allows the judges to invent new laws of contempt, and the House of Lords has said it is entirely beyond the judges’ powers. The rules do not allow new laws of contempt be created. The rules say that the proceedings are in private but that the press and legal bloggers may attend. The rules do not say anything about what the press and legal bloggers may or may not report.

19. My conclusions have been well-summarised in the judicial E-letter thus:

i) From the start of the era of judicial divorce, proceedings were in open court or in chambers “as if sitting in open court”. Scott v Scott [1913] AC 417 definitively established that the Divorce Court was governed by the same principles in respect of publicity as other courts.

ii) “At the heart of the concept of the rule of law is the principle that laws should be publicly made and publicly administered in the courts” Lord Bingham in The Rule of Law (Allen Lane, 2010, p.8).

iii) The rule of open justice is an “ancient and deeply entrenched constitutional principle in this country and elsewhere in the common law world”.

iv) Article 6.1 of the European Convention on Human Rights incorporates the common law rule of open justice.

v) When the ECHR was incorporated into domestic law by the Human Rights Act 1998, Parliament inserted s.12(4) which requires the court to have “particular regard to the important of the [Article 10] right to freedom of expression”.

vi) B v United Kingdom, P v United Kingdom [2001] 2 FLR 261 determined that a combination of the 1991 Family Proceedings Rules and s.12 Administration of Justice Act 1960 provided an exception for private law Children Act 1989 proceedings, but the exception means only that secrecy in those cases will not breach Article 6. It does not in any event apply to financial remedy cases.

vii) In light of Scott v Scott, FPR 27.10 and 27.11 do no more than provide partial privacy: they prevent most members of the public from physically watching a case but do not impose secrecy on the facts of the case.

viii) No procedural rules have ever supported the view that hearings in chambers were secret.

ix) Journalists and legal bloggers can attend a financial remedy hearing pursuant to FPR 27.11 and can report anything they see or hear at the hearing unless the case relates wholly or mainly to child maintenance and/or there is an RRO or anonymity order. This right is not constrained by the fact some of the information has been provided by the parties compulsorily.

x) Save where there is an RRO in place, parties to the proceedings can talk to whomever they like (including the press) about a financial remedy hearing but cannot show documents to a journalist unless that journalist was covering the case because parties are bound by an implied undertaking not to make ulterior use of documents compulsorily disclosed by their opponents.

xi) The standard rubric on financial remedy judgments providing for anonymity is neither an RRO nor an anonymity order. There is a process to follow to obtain either order and the latter order will be made only exceptionally as it is a derogation from the principle of open justice and an interference with the Article 10 rights of the parties as well as the public at large.

xii) Such orders can only be made by the Court once the “intensely focussed fact-specific Re S” exercise of balancing the Article 6, 8 and 10 rights has been undertaken.

xiii) The Judicial Proceedings (Regulation of Reports) Act 1926 does not apply to financial remedy proceedings.

20. As to the proposal that the Family Procedure Rule Committee should make rules to standardise anonymisation of the parties unless the court decides otherwise, for those rules to have ‘teeth’ any breach would have to be punishable as a contempt of court. New rules to give effect to this are beyond the powers of the Rule Committee (ss.75 and 76, Courts Act 2003) and would therefore require primary legislation.