Fair Shares and the Financial Reality of the ‘Everyday’ Divorce

Published: 13/03/2024 07:00

Introduction

The Fair Shares research study provides the first nationally representative picture of the financial arrangements made by divorcing couples in England and Wales.

While approximately 100,000 couples divorce each year, of these only around one-third leave the marriage with a court order in relation to finances, with the vast majority of these being made by consent.1 Previous research through court file surveys has provided only a partial picture of the court population, but given the methodological difficulties in accessing the non-court population, very little was known about the two-thirds of couples who do not go to court.

The law governing finances on divorce, contained in the Matrimonial Causes Act 1973, has been subject to increasing criticism in some quarters in recent years. However, much of this criticism has been based on high-value reported cases, which make up a tiny minority of the general divorcing population. In light of the Law Commission of England and Wales undertaking a Scoping Review of the law of financial remedies, the findings from the Fair Shares study land at a crucial moment.

Our survey data, based on responses from 2,415 participants who had divorced within the past 5 years, together with data from interviews with 53 divorcees, sheds light on the full range of divorces, providing data to fill a major gap in the knowledge and understanding of what divorcees do and how they do it.

In this article, we provide an overview of some of the key findings of the research study, focusing on the financial reality experienced by the ‘everyday’ couple. We will also briefly consider the implications of these findings in the context of recent substantive law reform proposals. A more detailed outline of the study’s methods and aims can be found in the Spring 2023 issue of this Journal2 as well as in the full report.3

Divorcees’ financial circumstances at the end of marriage

The context in which couples enter the divorce process is crucial to understanding the financial arrangements that emerge at the end. Their financial circumstances, including the level of income that came into the household during the marriage, the assets and debts they had accumulated, and whether one or both had a pension, are relevant to the level of financial security they will experience after they are divorced.

Most divorcees in the study had relatively modest amounts of wealth to divide at the end of their marriage. The median value of divorcees’ total asset pool including home and pension was £135,000. Nearly one in five (17%) had no assets to divide and 63% had total assets worth under £500,000. Although 68% of divorcees had been living in owner-occupied matrimonial homes, once mortgages were taken into account, 34% of these had homes with an equity worth less than £100,000, with only 7% reporting an equity above £500,000; 28% of divorcees were renting, the majority in private tenancies.

Most divorcees had not enjoyed significant wealth during their marriage. Two in five (43%) reported that their net household income was under £2,000 a month when they separated, and only 8% had a disposable monthly income of £5,000 or more. Nearly a third of divorcees (31%) said that they had no savings or assets (other than a pension or matrimonial home) at the point of divorce, and 17% had no assets to divide, while 12% had only debts. Indeed, two-thirds of divorcees (65%) had debts at the point the divorce process began. For some, these were modest (e.g. 16% had debts under £5,000), but 14% owed £20,000 or more.

So, the picture of couples’ financial position at the point of divorce was quite contrary to the impression given by the media’s reporting of divorces. Most divorcees did not enjoy lives of luxury during their marriage and had relatively modest amounts of wealth to divide at the end.

The study also reflected well-established findings that wives, and particularly mothers, were in more precarious financial positions at the point of divorce than husbands.4 Wives were more likely to have only part-time employment during the marriage and to earn less than husbands, with 28% having take-home pay of under £1,000 per month compared to only 10% of men. The position was particularly precarious for mothers; among women in paid work, mothers were far more likely (32% of those with dependent children and 39% of those with older children) than working women without children (20%) to have a net monthly take home pay of less than £1,000.

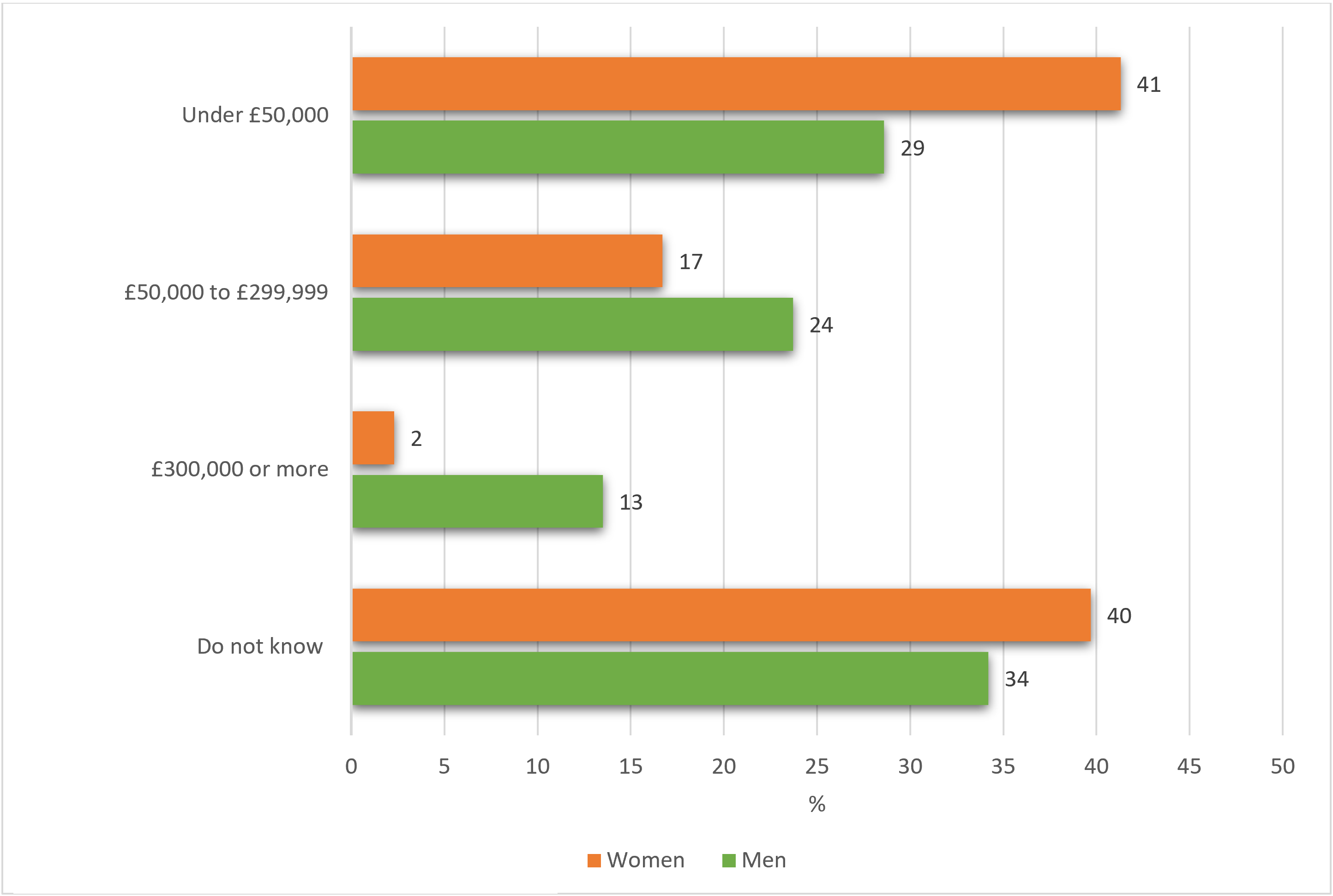

Relatedly, women had accumulated poorer pension provision. Although women were as likely as men to have a pension, men were more likely to have paid into it for longer, and their pensions were worth more than those of women. Figure 1 focuses on pensions not yet being drawn, but the pattern is similar for those already being drawn.

There is a stark picture presented of women being more likely to have a lower value pension than men. Among women with pension pots, four in ten women had a pot worth less than £50,000, compared to three in ten men. And among men with pension pots, 13% had a pot worth at least £300,000 compared to only 2% of women.

Overall, this highlights a particular financial vulnerability for women. Their lower value pension pots are likely to impact on their financial security in retirement, particularly if they have taken the main responsibility for childcare post-divorce and are unable to make decent contributions to a pension scheme over the coming years.

We will address the issue around the fact that so many divorcees did not know the value of their pension pot (final two rows in the Figure 1 bar chart) later in the article.

Figure 1: Pensions not yet in payment, by gender

Bases: female divorcees with a pension pot (854); male divorcees with a pension pot (610).

Dividing the assets: equal sharing of assets not the norm

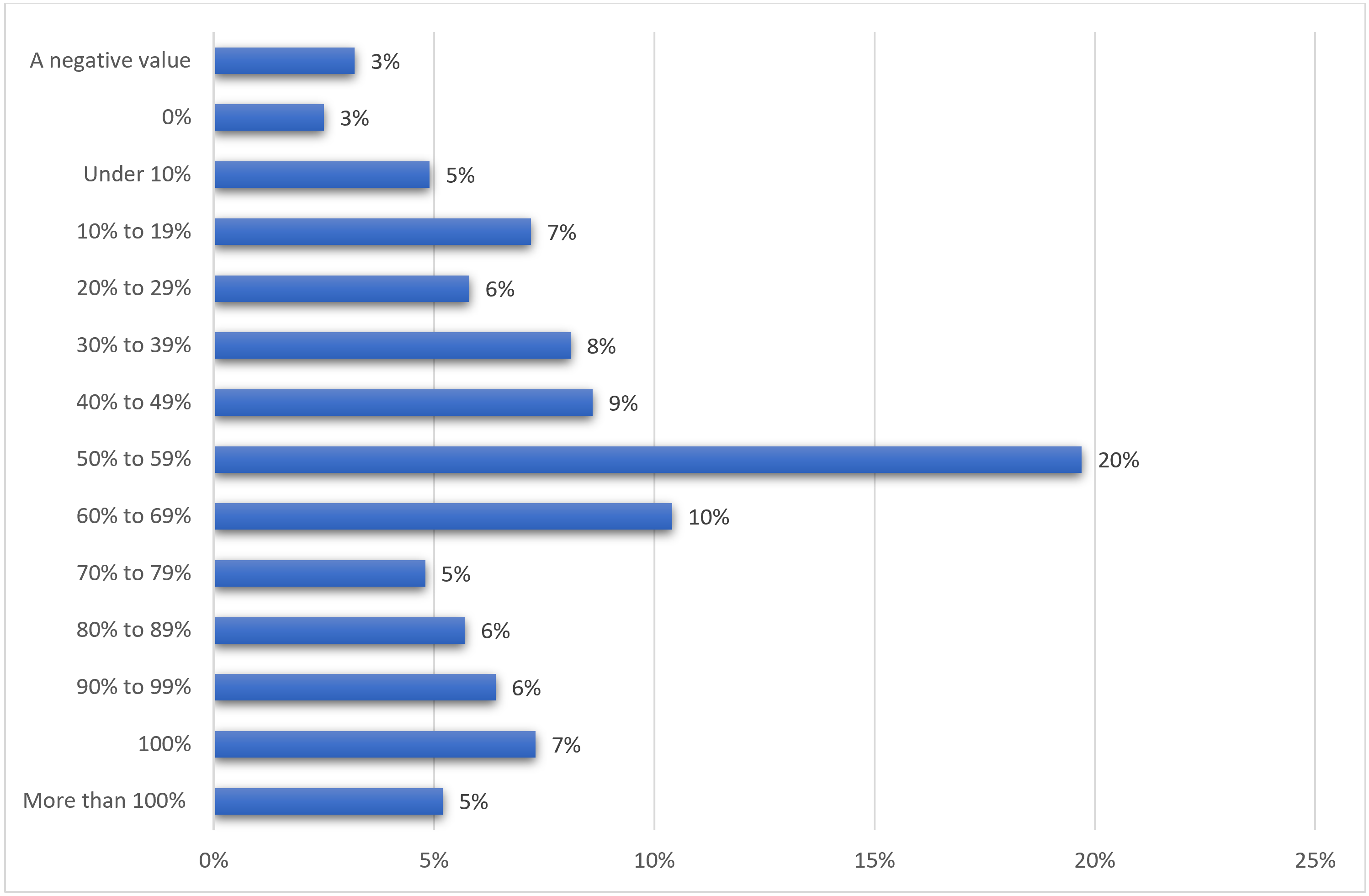

As outlined in Figure 2, only around three in ten (28%)5 divorcees who had divided their assets at the point of the survey reported receiving roughly half (between 40 and 59%) of the total asset pool. This meant that the majority shared out their assets unequally, with a third (32%) of divorcees reporting receiving a percentage share of less than 40%, including 3% who took on more debts than they received in assets (reported here as ‘a negative value’) and a further 3% who received nothing. Two in five (40%5) divorcees reported receiving more than 60% of the total asset pool, including 7% who received all of the pool and a further 5% who received more than 100%, possibly as a result of their ex-spouse taking on debts.

Figure 2: Percentage of the total asset value received by divorcee

Base: all divorcees who had divided assets (excluding those with only debts) for whom a calculation could be made (1,280).

The interview data suggested that the reasons for divorcees sharing out their assets unequally reflected need, individual circumstances and differing motivations amongst divorcees, such as wanting a clean break. One wife who was still waiting for the sale of the marital home to go through and the equity to be split, explained that she had agreed to take less equity than she originally expected, in the hope of having a clean break:

‘I wanted to end up comfortable, that I could afford to buy a property, which I am in the process of [although] not the one I wanted. I’ve taken less but I feel now I can have a clean break, by taking less, as long as he keeps his side of the bargain, fingers crossed that he will.’ (Wife 7)

Many interviewees also spoke about compromising or conceding when it came to the division of finances in order to spare their children from the emotional upheaval of divorce as far as they could:

‘I know the impact that a separation can have on children. So, to me, that just trumped any argument over debt and finance and everything else. … [I]f that meant swallowing a bitter pill over finances, that is, I think, where he trumped me in a way because I wasn’t, I just wasn’t prepared to argue over money.’ (Wife 28)

The study found that there was no statistically significant difference between men and women in the value of the shares received, but what did differ between them were the factors tending towards them receiving the larger share in any unequal division. For men, being less entangled in the marriage, such as having no children, or being younger, married for a shorter time, and having fewer assets, pointed towards doing better than their ex-spouse. For women, the reverse pattern was exhibited, though more weakly.7 However, having a larger pension at the point of divorce was associated with receiving a larger share of the combined asset pool for both women and men, underlining the potential for pensions to make a significant difference to an individual’s financial position post-divorce.

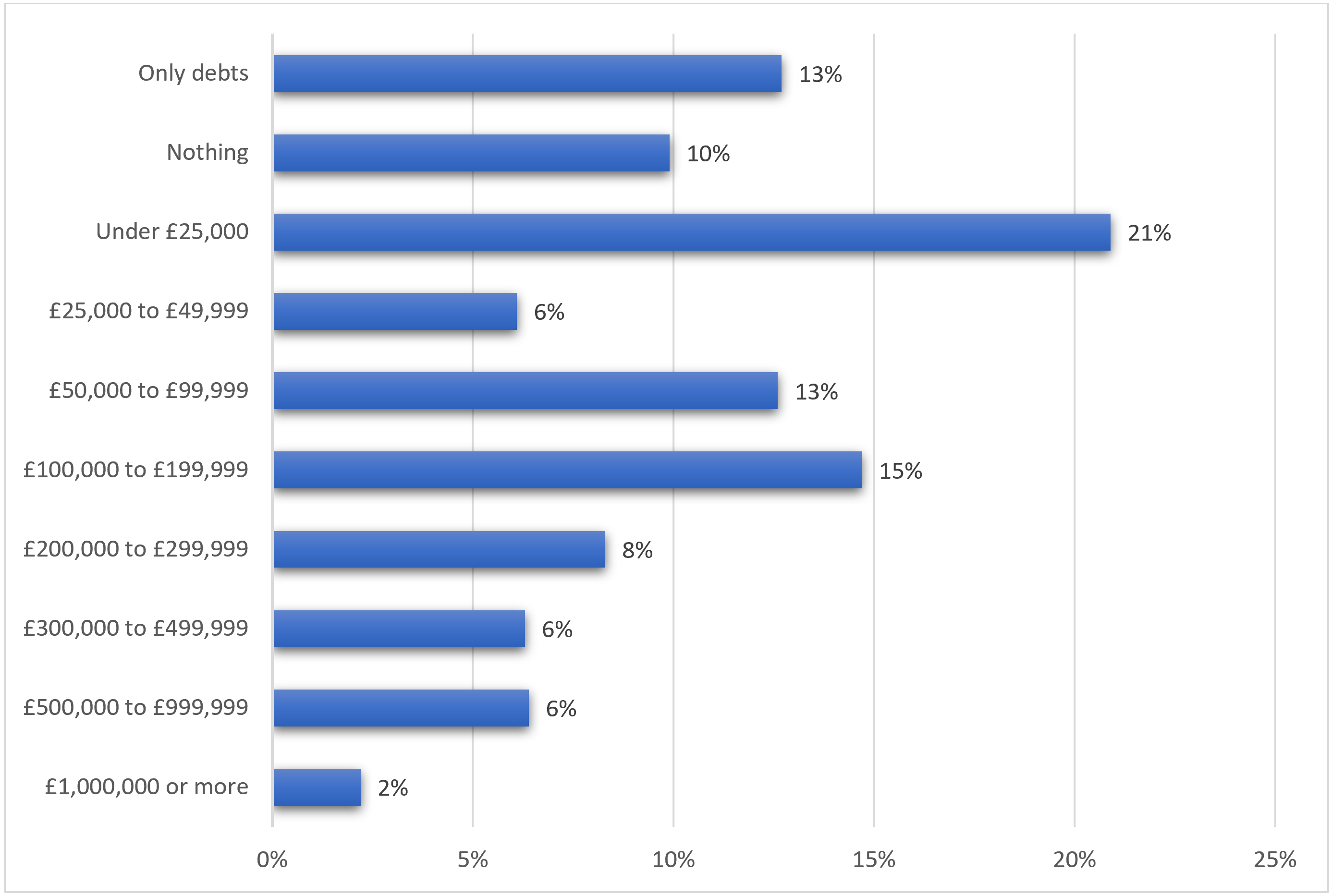

Since the median value of divorcees’ total asset pool was £135,000, it is unsurprising that half of divorcees who had made arrangements across all of their assets received less than £50,000. Figure 3 breaks down the value of the money and assets that divorcees received when they had settled all their finances, net of debts. It highlights both the fact that many divorcees came out of their marriages with nothing, and the modest value of the money and assets that other divorcees received. Almost a quarter (23%) ended up with nothing (10%) or only debts (13%).8 A further one in five (21%) ended up with money or assets worth under £25,000 and only 9% came out of the marriage with £500,000 or more. The picture that is painted is thus of many divorcees ending up with very little, not unexpectedly, given the modest value of their assets.

Figure 3: Value of the assets and money received by divorcee

Base: all divorcees who had divided assets (including only debts) for whom a calculation could be made (1,449).

The particular problem of pensions

A worrying issue that came through from the data, was the lack of awareness, understanding or interest in pensions amongst many divorcees. One interviewee knew that her husband had various valuable pensions, but had ‘no idea’ how much they were actually worth:

‘He’s worth an absolute fortune when he dies. … [but] if there was a way around him not giving me any money, he would find that way. So I didn’t look into it. If you don’t know what you’re missing, you don’t mind.’ (Wife 27)

This lack of awareness and understanding of pensions fed through, as one would expect, into how, if at all, pensions were taken into account when couples sought to make their financial arrangements.

Over a third (37%) of divorcees with a pension not yet in payment did not know the value of their own (let alone their ex-spouse’s) pension pot, with women (40%) more likely than men (34%) to say that they did not know (see Figure 1). In addition, nearly a quarter (23%) of those with an employer pension did not know what kind of pension scheme they were enrolled in, whether defined benefit or defined contribution. Furthermore, only 11% of divorcees with a pension yet to be drawn had made an arrangement for pension sharing, with men (14%) much more likely to report sharing their pensions than women (3%). Pensions were significantly more likely to be shared where they were of higher than lower value or where there were dependent or non-dependent children.

Reflecting earlier research,9 it is therefore unsurprising that this study found very low levels of pension sharing. Interviewees frequently told us that pensions ‘had not come up’ in discussions over financial arrangements, including even when lawyers had been involved.

But this was not necessarily only due to ignorance. A spouse might not actually want a share of the other’s pension. A husband noted that although his wife:

‘could take 50% of [the pension] She decided not to. I don’t know why. … [I]t’s been a bonus, like the whole pension thing, that she hasn’t … I was prepared to like, lose half my pension, but the fact that she said she didn’t want it, that’s been a bonus.’ (Husband 25)

The prevailing view appeared to be that pensions are entitlements of the individual concerned, and generally to be preserved by that person, rather than ‘marital assets’ available to be shared. Where pensions were considered, a lack of legal knowledge and advice might well lead some divorcees to make unwarranted assumptions or bad bargains regarding what to do with them. Where a pension not yet in payment was shared, there was an equal split of the participant’s pension in only 22% of cases. In nearly half of cases the recipient received less than half and in 18% over half.

Myth vs reality: spousal periodical payments

The issue of spousal maintenance has received particular attention over the last few years in England and Wales. Claims that the current law provides ex-wives with a ‘meal-ticket for life’ have been used as a rationale to suggest reforms which would limit the spousal maintenance period. However, the findings show that only 22% of divorcees reported having had a spousal maintenance arrangement at the point of divorce (by the time of the survey, this percentage had dropped to 14%).

A number of principal reasons came through from the interview data as to why most couples had no ongoing spousal maintenance arrangement. For many divorcees, the issue was simply not on their radar when going through divorce; others mentioned the practical reality of affordability; the desire for a clean break; the need to demonstrate financial independence from the other spouse, as well as domestic abuse issues with the victim of the abuse wanting to be away from the perpetrator and not wanting to communicate with them going forward.

Where spousal maintenance was paid, women were more likely to receive maintenance than men, but this was nearly always for a fixed term, with 88% of arrangements for a specified period, either defined by a particular event, or an agreed number of years. The payment of spousal maintenance was also associated with a certain amount of vulnerability on behalf of the receiving spouse; for example, where spousal maintenance was paid, it was often connected with having (or having had) children, or with the recipient having an illness or disability.

Therefore, there was nothing within our findings to suggest that maintenance was being used as a ‘meal-ticket for life’ for the wife. Instead, payments appeared primarily to be used to address the adjustment to post-divorce living arrangements, such as to meet housing and household expenses.

Achieving ‘fair shares’ – policy thoughts and recommendations

This article has focused on the financial reality experienced by the ‘everyday’ couple on divorce.10 As the Law Commission begins its scoping exercise, our findings suggest that it will be vital for policy makers to focus on the circumstances of the majority of divorcees who have limited means, rather than on the concerns of the very wealthy whose stories tend to dominate media accounts. Furthermore, the current broad discretion provided by the law to shape financial arrangements to meet the individual circumstances of each couple appears both appropriate and necessary, given the range and disparities in wealth and earning capacity of the divorcing population, and couples’ own priorities and circumstances. It is doubtful that laying down a strong legal presumption of equal sharing of assets or limiting the time period for spousal periodical payments would deliver a substantively fair outcome between divorcees or reflect their own priorities. To the contrary, it would be more likely to cement inequality as between husbands and wives, with mothers and older wives doing particularly badly.

Instead, policy makers need to focus their attention on how to enable and encourage couples to take full account of all of their assets and their future prospects when deciding on what would be the appropriate outcome for them and their family. In particular, greater consideration needs to be given to how pensions may more readily be factored into the arrangements that couples make, if real fairness, as distinct from notional ‘equality’, is to be achieved.