DR Corner: Fair Shares – Mediation Under the Microscope

Published: 13/03/2024 07:00

1 November 2023 saw the launch of the Fair Shares report, which presents the results of the first fully representative study of the arrangements families make on separation and divorce.1 Following a bespoke survey of 2,425 individuals who had divorced in the last 5 years, the report helps us to understand the trends amongst the full (approximately 100,000-strong)2 population of divorcing couples. Roughly two-thirds of the general divorcing population do not obtain a court order dealing with financial matters and are, therefore, not captured in previous studies of financial arrangements based on the court files.

A key finding of the report was that the median value of divorcing couples’ pool of assets was £135,000. The study therefore captures the experiences of those whose lives before, during, and after divorce are markedly different to those featuring in reported cases concerning substantially higher assets. As those of us practising in the area are well aware, the field of divorce and financial remedies is much broader than headline-grabbing cases involving millions of pounds. Policymakers considering the reform of financial remedies law (for whom this report comes at an important juncture given the government’s proposed review of financial remedies law and the Law Commission’s ongoing work) will be helped by the broader view of the impact of financial remedies law which this report offers.

Non-court methods of dispute resolution were front-and-centre of the findings. This is unsurprising given what was already known about the number of financial remedy cases which are resolved on a non-contested basis. (From July to September 2023, for instance, 70% of financial remedies applications were uncontested and 30% were contested at the time of application, many of which will also have gone on to be settled during the court process.3) Therefore, not only can the report inform the way the government approaches the substantive law going forward, but it can feed into policymakers’ approach to promoting and supporting non-court dispute resolution.

This article focuses on the findings of the report insofar as mediation is concerned, including the lessons which may be learned. The authors approach this from the perspective of being (in one instance) a mediator, in the other a keen supporter of mediation. However, even the most ardent advocate for mediation would accept that it is not a silver bullet and not suitable in every case. Mediation has been heavily promoted by the Ministry of Justice as a means of reducing the significant burden on the Family Court and supporting families to resolve arrangements through a less adversarial process.4 Since March 2021, the government has operated a (highly successful) Family Mediation Voucher scheme, offering a one-off contribution of £500 towards the cost of mediation in eligible cases.5 In March 2023, the government launched a public consultation about measures aimed to increase the use of mediation in family cases, including introducing a mandatory requirement to mediate before a court application is made.6 The government’s response to that consultation is understood to be imminent.

Data from the Fair Shares report as to the uptake of, reasons for, experiences of, and results of mediation shed light on the challenges mediation can face. What is clear is that mediation is not a panacea, and that a narrow view of the ‘success rate’ of mediation should not be allowed to cloud the government’s vision when it comes to the need for other resources for divorcing couples.

Uptake of mediation

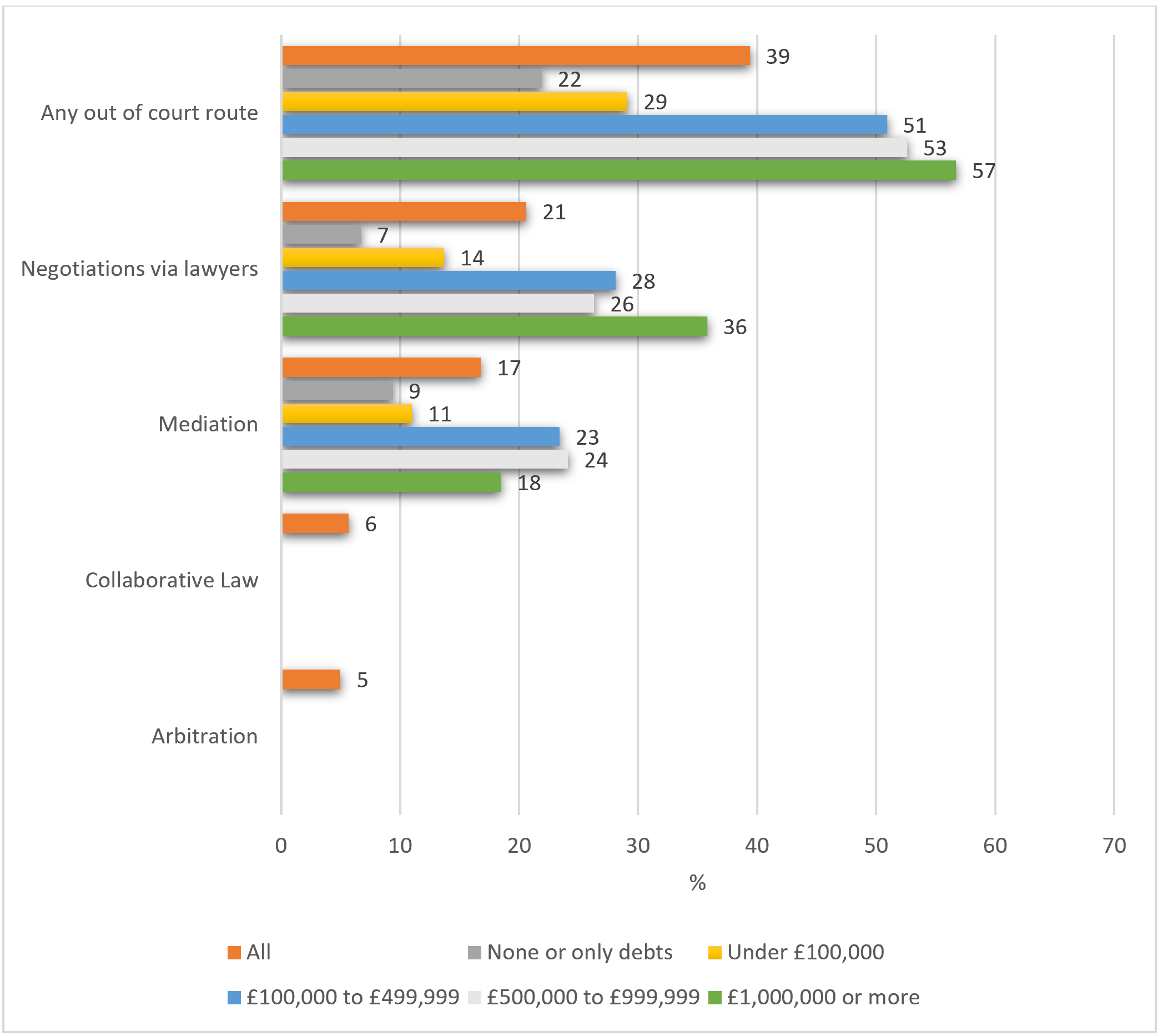

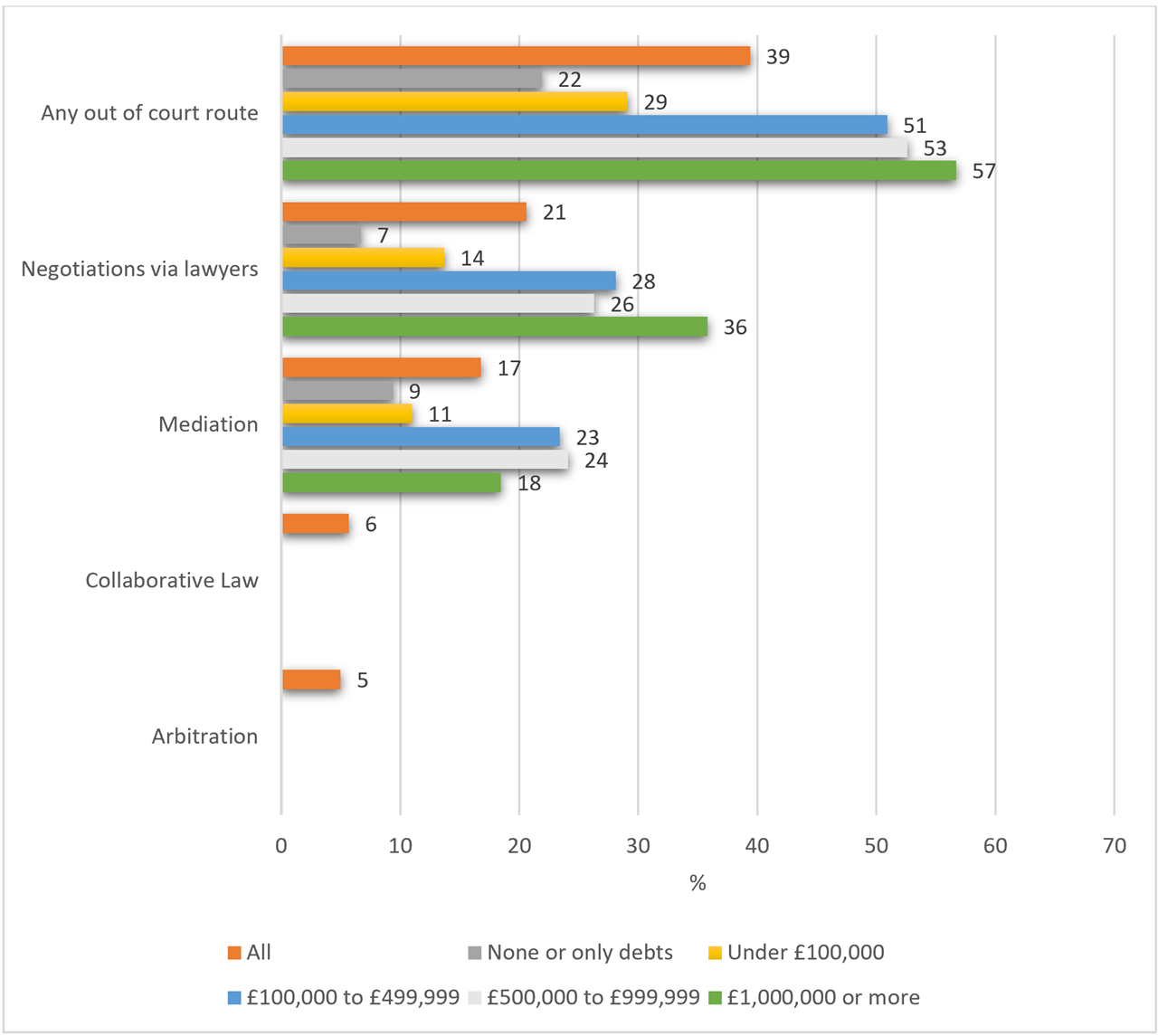

Figure 1: Non-court routes to attempt to make a financial arrangement

Base: all divorcees (2,415); divorcees with no assets or only debts (276); divorcees with assets under £100,000 (570); divorcees with assets between £100,000 and £499,999 (850); divorcees with assets of £500,000 to £999,999 (326); divorcees with assets of £1,000,000 or more (261).

Amongst those surveyed as part of the Fair Shares project, mediation was the second most popular form of dispute resolution, coming in closely behind solicitor negotiation. Figure 1 shows that 39% of the divorcees surveyed had used one or more forms of dispute resolution, of which 17% of divorcees reported having tried mediation.7

In speculating as to the reason for mediation’s popularity compared to other forms of dispute resolution, it is tempting to assume that mediation is simply better-known amongst the general public than, say, collaborative law or arbitration. A third of divorcees said in the Fair Shares survey that they had used government websites as a source of information, making the Ministry of Justice’s publications an important source of information and signposting, which might be responsible for raising consciousness of mediation compared to other processes.8

In the data gathered, the strongest predictor of using mediation was having used a lawyer: 28% of those who had engaged with lawyers reported having tried mediation, compared with 11% of those who had not.9 Uptake was higher amongst those with greater assets to divide, which mirrors the position regarding the taking of legal advice. It is clear that lawyers have an important role to play in providing information and signposting to help divorcing individuals decide by what process they will resolve matters and the appropriate parameters of settlement. The correlation between use of lawyers and uptake of mediation might be taken to show that mediation is a favoured form of dispute resolution amongst legal practitioners. Potentially counter to this, though, is the fact that use of mediation and use of providers of legal services were both higher in cases where the overall assets were higher. Those who see a lawyer may already be predisposed to consider mediation (for instance because they have assets available to fund the process) compared to those who don’t. What is clear, however, is that lawyers play a vital role in signposting people away from court, as shown by the fact that mediation numbers fell off a cliff in the wake of LASPO.

The report shows a continuing lack of understanding about mediation amongst the divorcing population. The researchers highlight that ‘some interviewees told us that they had not heard of mediation or had thought it related to disputes over children’.10

One interviewee cited in the report described a process where the parties were in separate rooms and a mediator shuttled between them. He falsely referred to this as ‘arbitration’.11 This perhaps goes to show that the public consciousness of ‘mediation’ is associated with a single mediator and two clients round a single table. The uptake of mediation may be greater – and perhaps even the outcomes of mediation more successful (more of which below) – if the divorcing population was more aware of the range of formats mediation can take, such as mediation with multiple co-mediators, a multi-disciplinary team involving additional professionals (e.g. a financial expert, a therapist), mediation with lawyers attending, and ‘shuttle’ mediation where the parties need not be in the same room.

Based on this information, although none of the main mediation organisations support government proposals to introduce mandatory mediation, its use may well be increased by improving divorcing couples’ understanding of mediation. That may particularly be the case if information provided to divorcing couples broadens awareness of mediation to include a wider range of models (e.g. shuttle mediation). The strong link between use of lawyers and attendance at mediation suggests that funding for early legal advice would be an effective way to increase proper understanding of mediation.

However, getting couples through the door into mediation is not the only challenge if the goal is to bring about satisfactory resolution of financial remedy matters.

Reasons for not using mediation

Notable for the government’s proposals for mandatory mediation are the parts of the Fair Shares report which shed light on the reasons given by those who chose not to pursue mediation (including by those who were clearly aware of it as an option). As the authors of the report summarise: ‘The reasons for using lawyers, and using courts, in preference to mediation, were primarily concerned with a lack of ability to negotiate with the other spouse.’12

The extracts from interviews provided in the report are illustrative of this, with one individual stating, ‘Nobody who was ever going to be able to help us meet in the middle … and we would have paid out money then that we didn’t have.’ Another said that, ‘[Mediation] was never discussed because he would have never done it. You’d have got more information talking to a tree …’.

These reactions to mediation suggest that there may well be a ‘ceiling’ to the number of people who can be encouraged into mediation by ‘nudging’ from the government. From an ethical perspective, there is also a limit to how far government ‘nudging’ can go when some divorcees clearly do not feel comfortable negotiating with their spouse, or identify that they do not feel their spouse will enter into mediation in good faith. Self-evidently, it is also important to ensure that where there is/has been domestic abuse, there is very careful screening and consideration as to whether mediation is the right process (and, if so, how that is to be managed).

The government’s schemes to promote mediation should not therefore be at the expense of providing solutions for those who, for reasons they have carefully considered, choose not to participate in it (or for whom it is clearly unsafe). For that category of divorcing individuals, the Fair Shares research would suggest that solicitor negotiation is the current most opted-for route (for which there is no financial support from the government, post-LASPO).

Experience and outcomes of mediation

When it comes to those who have attended mediation, the report shows that divorcees’ experiences of mediation were mixed. While some individuals who had attended mediation reported that it had been helpful, others found that it had been unproductive, unduly expensive, that they had felt ‘forced’ to attend, or that the sessions themselves had involved ‘fight, fight, fight’.13 This supports previous research, in the context of family matters more broadly, showing that mediation does not always match up to participants’ expectations, and can be a difficult experience for those who attend.14

In terms of the outcomes of that difficult process,15 13% of agreements reached in respect of financial arrangements were made by those who had attended mediation.16 Just under half (45%) of agreements reached in mediation were made into consent orders (compared to 72% of arrangements reached via lawyers).17 This proportion was lower than for agreements reached between the parties themselves (48%).18 This data might come as a surprise to legal practitioners, who – in the light of Wyatt v Vince [2015] UKSC 14 – will approach financial remedy cases on the basis that only an order of the court can bring matters to a final conclusion.

Perhaps even more surprising is the finding in the Fair Shares report as to divorcees’ perceptions of the effect ‘on the ground’ of the outcomes of mediation. Survey participants who had made arrangements were asked whether those had worked out as expected. Of those who had a full (rather than partial) agreement, only 44% of participants reported that arrangements made in mediation worked out as expected, compared to 79% in the full sample of divorcees.19

These findings call into question the government’s claim that mediation has a ‘69% success rate’.20 That claim is based on the results of a questionnaire answered by mediators participating in the government’s family mediation voucher scheme, and represents the number of families who took up the scheme and reached an agreement on all or some issues in mediation.21 The results of the Fair Shares research suggest that even amongst the ‘successes’ of mediation, there is a significant proportion of cases where agreements reached are never placed on a formal footing, or to some extent unwind.

The authors of the Fair Shares report give the following theory as to why arrangements reached in mediation are failing in such high numbers to live up to expectations: ‘Those undertaking mediation may already have tried and failed to negotiate an agreement between themselves (including with the help of lawyers), so that when they did then reach a settlement via mediation, it may have been the result of a rather grudging compromise rather than a real meeting of minds and thus more likely to unravel when it came to be implemented and a party had second thoughts.’22 In other words, the causality is not between mediation and unsatisfactory outcomes, but between ‘difficult cases’ and unsatisfactory outcomes. Then, separately, we might wonder whether difficult cases are being funnelled inappropriately into mediation.

Previous research, cited in the Fair Shares report, has demonstrated that one of the most important indicators of whether or not people will come to a settlement in financial remedy matters is emotional willingness to settle.23 That does suggest that there will always be a category of divorcing couples for whom mediation is unlikely to result in anything more than a ‘grudging compromise’ which may later unravel. In those cases, mediation may not be capable of bringing about long-term resolutions, and the new data suggests that cases falling into that category may have been ‘hidden’ within the figures for successful mediations. With this in mind, a government ‘push’ towards mediation cannot replace the proper funding of systems to support individuals within that cohort, including the funding of legal advice, and a fully functioning Financial Remedies Court.

Conclusion

The lesson to be learned is that mediation cannot be assumed to be the end of the story, any more than it can be regarded as a panacea.

There may be some scope for further increasing the uptake of mediation, particularly by improving access to information about mediation and the breadth of forms it can take. Given the strong link between use of lawyers and attendance at mediation, this information may be in the form of early legal advice. In addition, mediation is not ‘proper’ mediation without the ability on the part of the participants to take at least some legal advice along the way, and to ensure that any agreement reached is properly embodied in a consent order. It is not just about initial advice and signposting.

However, there is likely a ‘ceiling’ to the number of cases which can – or should – be signposted into mediation. Future measures seeking to bring about resolution of financial remedy matters must take a more holistic view of the ‘success’ of a financial negotiation, and support divorcing couples to make arrangements which work in the long term and can be properly formalised.