Dodgy Digital Documents: Where Are We Now? Where Are We Going?

Published: 06/07/2022 07:13

In the sun-kissed, halcyon days of late 2019 when Brexit had not yet taken effect and a corona was a halo of gas seen around the sun during an eclipse, a fevered discussion was taking place on Twitter between family lawyers regarding the increasing frequency with which we were seeing manipulated digital documents and recordings in family proceedings. In 2019 and 2020 this discussion prompted articles,1 a podcast with me, Byron James of Expatriate Law, and Ben Fearnley of 29 Bedford Row,2 and a seminar with District Judge Devlin of Oxford Family Court.3 The issue was also discussed by me and Byron James with Joshua Rozenberg on BBC Radio 4’s Law in Action.4 Those of us interested in the issue thought we had shouted loud enough for all to hear and for lay clients, lawyers and judges alike to be aware of the issue and what to look out for. It appears that we were wrong.

I was recently asked to speak again on the topic to a collection of judges, and the reactions of horror and incredulity from the audience that met my talk prompted the Chair of the Editorial Board of the Financial Remedies Journal, who was also in attendance, to ask me to write an article updating the position. So, where are we now?

The increased use of digital documents during and post the COVID-19 pandemic and their exploitation

Prior to March 2020, only a select few family and private client barristers and solicitors used and were familiar with digital documents and bundles to conduct their practice. It remained the norm to use paper copies and originals of documents and bundles. The need to work from home and the belief that the novel coronavirus was transmitted through droplets which would fall on documents and remain contagious meant that all institutions made far more use of modern technology, first scanning hard copy documents, so converting them into portable document formats (PDFs), then moving to downloading documents directly from websites as PDFs and saving them or otherwise ‘printing’ them as PDF documents. Coincidentally, at the same time in the Family Division of the High Court and in the Family Court, Mostyn J was pursuing compliance with the Financial Remedies Court Good Practice Protocol of 7 November 2019 and, on 3 March 2020, sent out an e-bundles protocol permitting the use of e-bundles with the court’s permission and directing how those bundles should be prepared.5 I believed that, as practitioners became increasingly familiar with digital documents and how commonly available software could be used to manipulate them (since that is what we do when we create e-bundles), practitioners would be less surprised with the ease by which an opportunist would be willing to amend documents to suit their case in court, but it appears that there are many of us who remain unaware of the problem.

The COVID-19 pandemic and remote working has given rise to another issue, namely that where all documents are now digitised in solicitors’ files, there is a temptation, frequently indulged, to transfer to counsel and/or to the court all the papers available in any one case. In that way, the solicitor can be sure that nothing that needed to be passed on has been missed. The effect can be that in the limited preparation time available for any one case, when trying to read all the documents provided (sometimes many thousands of pages), some may be skim read (in a bundle of up to 500 pages they would be properly considered), and discrepancies can be missed.

In my experience, we remain far too trusting to accept the contents of documents for the truth of what they say. We do not scrutinise for inconsistencies with sufficient rigour. We often do not have the time or facility to be able to do so. As practitioners and judges we are expected to pick out the most important points of an argument or a document and concentrate on them. In doing so, we ignore apparent or supposed peripheral issues, such as the state of, kemptness or wording of any particular document, and it is this ignoring that manipulators of documents exploit.

What can be manipulated and how?

Documents

In my earlier articles I explain how digital documents can be manipulated (including those from institutions such as pension funds, banks, local and central government, employers, etc). The likely manipulator can do it in a number of ways:

- downloading documents from those institutions and, providing they are not protected by significant security (and they often are not), opening them in Microsoft Word, Google Docs or a similar program and re-writing them with the content they want to show;

- if they cannot be manipulated due to security settings (more frequent now than 2 or 3 years ago), then they can be printed with a good quality colour printer (inkjet will do) and then scanned into a digital format and manipulated thereafter;

- editing those documents in Adobe programs, such as Acrobat Pro, which can be downloaded and used free of charge for a trial period, or otherwise costs only around £15 a month. Adobe programs try hard to replicate the flaws already present in a digital document and will try to match fonts, including proprietary fonts, of documents. NatWest, for example, uses a proprietary font in its communications, and Adobe programs will automatically try to match that font with something so similar that it is unlikely to warrant any scrutiny;

- presenting amended spreadsheets of, for example, bank statements or otherwise micro-fiche-style documents of historical bank records, which are easily manipulable in Microsoft Excel or similar spreadsheet program;

- taking photographs of documents and editing them on a smart phone or tablet. Litigants in person frequently provide photographs rather than direct downloads of documents, so they are photographs of copies.

If a likely manipulator is not familiar with these tools, but is determined to present false documents, there are companies on the internet that will provide you with ‘novelty’ documents for a fee, all of which look completely real (see Figures 1 and 2).6 All of the sites come with disclaimers as to fraudulent usage of these documents, but they are also providing these documents for people to overcome, for example, money laundering checks (relevant for Know your Client protocols) and to provide proof of points in court or other formal proceedings.

Figure 1: Sample documents

Figure 2: Sample bank statements

Audio and video recordings

It is not just documents that can be easily manipulated. Byron James has had a case in which a mother had manipulated the contents of telephone calls and audio recordings of her former partner taken over a number of years, so that a telephone call shown to have taken place at a particular date and time from both parties’ telephone records and supposedly recorded by the mother, included clear and obvious direct threats of violence to her from him.7 The fraudulent evidence was only ascertained after the father insisted he had never said such things, and the recording of the telephone call was analysed. It transpired that the mother had used easily available smart-phone editing software and online tutorials to create that recording.

Again, if one is not sufficiently competent to make use of that software, then one can send out recordings to online companies with a brief to create a realistic ‘deepfake’.

The availability of powerful and complicated computer technology in smartphones and dash cams has made it possible for everyone to record everyone else all the time. How many of us have video and audio recordings of our friends, family and strangers? All of these electronic files can be manipulated and edited by easily available means and a little bit of time, so that one has an apparently original file.

In short, false representations can be very easily made. Courts and representatives need to be alive to the problem. It is surely more frequent than it was when one only had Tipp-Ex or scissors and Sellotape to edit documents.

How does one identify a fake document?

First, one needs to listen to one’s clients. Lawyers and judges should be prepared to listen to complaints when one party insists that what the other says cannot be true, or that their document or recording should not say what the representor says it does.

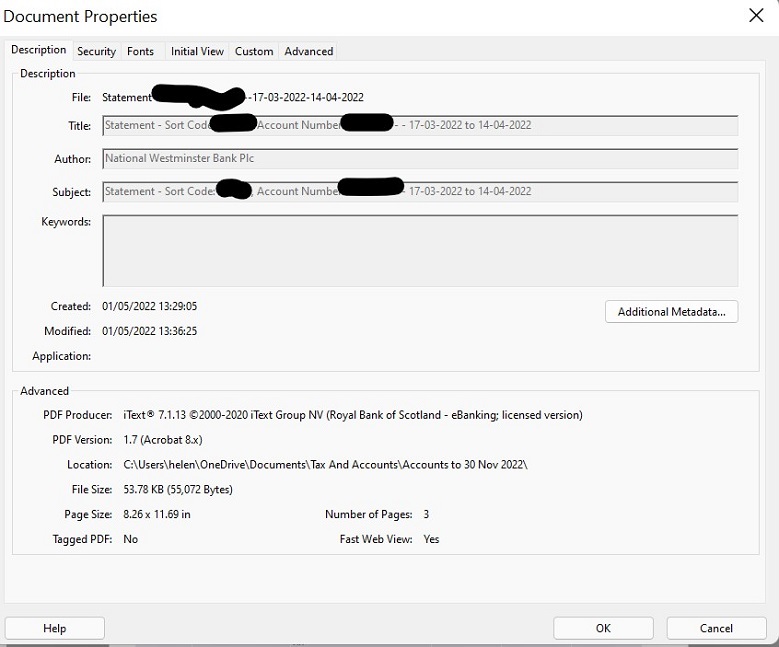

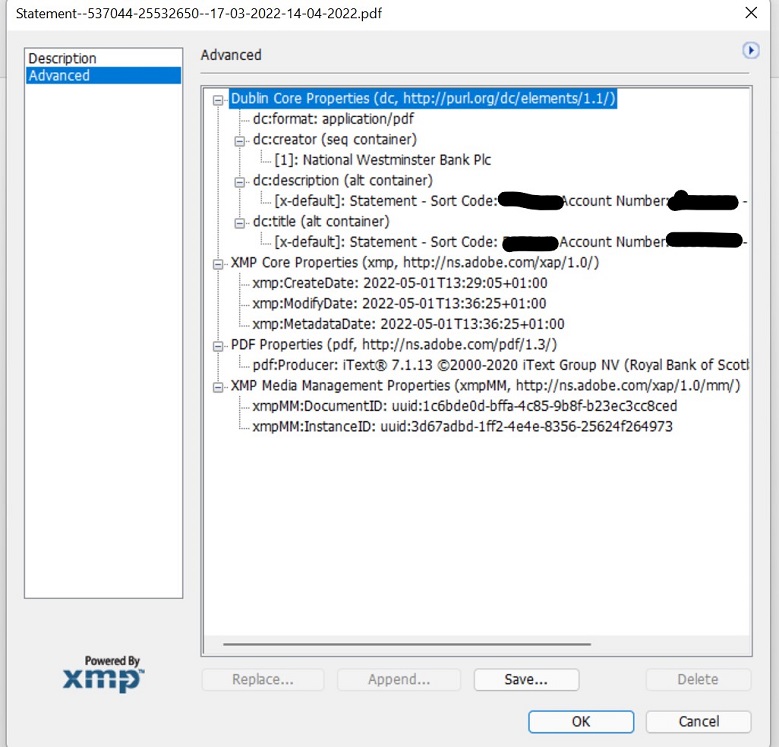

Secondly, always ask for the original version or download of a document. Electronic documents will have, in the information/properties tab of each document, details of who created it and when. If the document is a direct download from a banking institution, for example, the institution should show in the properties as the creator of the document (see Figure 3). The metadata under properties of a downloaded NatWest bank statement shows that the creator is NatWest. The additional metadata tab will take the scrutiniser to data that provides details of what the actual document is and when and how it was amended (see Figure 4).

Figure 3: NatWest document properties – description

Figure 4: NatWest document properties – additional metadata

If the document allows me to edit it, then I can do so, but the metadata will then show that the document has been edited by me/the person who has the software registered to them. If, however, I print it out, photocopy it, scan to PDF and email it to myself, the metadata will show the document as being created by me (or by whomever the software being used is registered). Frequently, documents are provided by clients to solicitors in just this manner. They might download those documents, print them, then scan and email them on, or otherwise download and print out the documents, before taking them into the solicitor, who then scans and saves them for later forwarding to others.

The direction in the good practice e-bundle guidance for a single, searchable PDF bundle has the potential to exacerbate the problem of manipulated documents to be provided to the court and to the other party. Historically, there would be a direction providing that original documents should be produced to the court at any hearing where they would be relevant. No more. Solicitors and parties have to provide a single e-bundle which, even if it is made up of multiple original documents, creates an entirely new document/file with its own metadata. Quite often, those bundles are made by creating a physical bundle of copy documents, which are then together scanned to PDF and subject to optical character recognition (OCR), before being indexed. Again this creates entirely new documents and the potential for investigating fakery is diminished.

Thirdly, where suspicion arises, scrutinise documents carefully for discrepancies. Look for anomalies such as slightly different fonts in documents, or page numbering/continuation that does not match. The fact remains that the better the fake, the more likely it is to be successful in its deployment. Examples of discrepancies arising are as follows:

- Manipulation of bank statements to show that a high-earning husband appeared to be earning very little, and so was unable to satisfy a maintenance order was discovered because ‘astute counsel’8 Ben Fearnley noted in cross-examination that one of the bank statements provided by the husband showed a transaction date of 31 September. When the husband was challenged about this, he said it must be the bank’s error. He was ordered by the judge to obtain a year’s run from the (offshore) bank overnight, and the husband purported to do so, producing those documents, plus a letter from the bank recording the apparent error. On the way to court that morning, Ben checked the metadata of the documents provided, and they all stated that they had been created by the husband. In cross-examination that day the husband had nowhere to go, having been caught. The court found against him and awarded the wife indemnity costs. He was also reported to the Director of Public Prosecutions, and was prosecuted for attempting to pervert the course of justice. He pleaded guilty. This middle-aged businessman of previous good character who did not want to pay his wife the maintenance to which she was entitled ended up with a 9-month sentence of imprisonment.9

- Council tax bills addressed to both parties and disclosed by one party to provide evidence that both parties were living in a property belonging to one of them on particular dates (relevant to contributions said to have been made) and when the other party denied that the discloser was living there should not include, on the face of them, the single person discount, as was the case in a matter in which I was involved.

- Where an email is produced by one party which is said to evidence an agreement to share interests in a particular property, the manipulator should ensure that all versions of that email are altered if they want to convince the court that what they say is correct. In the case in question, the email having derived from a company’s servers and back-up records to which the manipulator did not have access, the original was able to be retrieved showing the true wording of that email.

- If, however, the documents are produced by a company director or owner and are said to have been made on software belonging to that company, alarm bells should wail when that same director says the documents are no longer available as the computers have been wiped and destroyed and the electronic records no longer exist.

What to do?

Where suspicion arises in relation to the integrity of a digital document, a party or the court needs to grasp the nettle and deal with the problem. I have previously discussed the draft practice guidelines proposed by District Judge Peter Devlin and Byron James, which were considered by the Judicial Digital Steering Committee, but nothing has yet come of them. I reproduce them here, as they are excellent guidance for all practitioners and judges:

‘1. That the starting point is not to trust the content of any hard copy document which has not been subject to verification from the original third party source and/or the underlying metadata of the document.

2. In the normal course of disclosure the original electronic file of any document should be disclosed to the other parties and to the court, together with the electronic communication with which it was provided from the purported creator of the document. Those documents should be sent to a designated secure professional email address that the parties and the court can access.

3. PDF files should be the preferred file for documents (as the metadata can be easily verified). Screenshots and image files are inappropriate and should be rejected.

4. Where a question is raised regarding the veracity of a hard copy document or electronic file, the party producing the file should be required to answer a questionnaire detailing who was responsible for creating the document, their relationship to the person producing it, how the person producing came to be in possession of it, to confirm that they retain the original (hard copy or electronic original), and setting out how the electronic document has been held, saved and changed, if at all, by the person producing it.

5. Where the questionnaire is not answered, the court shall not assume the content of the document is accurate without independent third party verification.

6. Where there are inaccuracies/inconsistencies, then there should be verification by the third-party source, either by way of a third party disclosure order or a joint request from the parties.

7. If questions still exist, then forensic expert evidence should be sought and contempt/fraud warnings should be given.

8. If only hard copy documents are produced, without the original file or original document being available for scrutiny, then the court should consider making a specific finding about whether the producing party is able to rely upon that document in evidence.’

These proposals were met with a lukewarm reception in early 2020, but perhaps, given the realistic prevalence of document manipulation, they will be reconsidered.

I, too, have proposed a remedy that has met with an utterly cold reception (which I cannot understand), namely the use of an independent disclosure officer in private client and financial remedy cases. The parties should meet with that officer and download all their relevant disclosure in that officer’s presence, who can then verify its veracity and circulate to the solicitors/other parties and file electronically with the court. This would, in my view, completely minimise the opportunity for document manipulation. It would also minimise the desire to exercise ‘self-help’ methods of obtaining disclosure, now effectively outlawed by Imerman v Tchenguiz [2010] EWCA Civ 908, [2010] 2 FLR 814. It could be made a mandatory standard direction on Form C in advance of exchange of Forms E. Any other disclosure to be provided subsequently should be provided in the same way.

Conclusion

Document and digital file manipulation is a real and present problem in all litigation in which documents are deployed to support arguments or to prove facts. Judges and practitioners need to be aware and alert to it. The problem for any judge dealing with private individuals is, of course, the impact on them, their families and children, both of ignoring the manipulation and of referring the manipulator for consideration for prosecution or committal for a contempt of court. The consequences can mean that the breadwinner and/or parent receives a sentence of imprisonment and an inability to work in future, negatively affecting the welfare of the other members of the family. Despite this, the courts and practitioners must not and cannot ignore or acquiesce in this behaviour, which strikes at the heart of justice. Manipulation is easy to do and easy (if careful enough) to conceal. Fraudulent behaviour and attempting to pervert the course of justice should never be disregarded or brushed aside in the interest of reaching a practical and swift conclusion to litigation between private persons.