A Primer on Pensions and Percentages: AFW v RFH [2023] EWFC 119

Published: 27/09/2023 10:16

https://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWFC/HCJ/2023/119.html

I love this judgment of Recorder Laura Moys in the matter of AFW v RFH [2023] EWFC 119 as it gives a wonderful demonstration of:

- The neutrality of changes in public sector cash equivalent value’s (CEV) which give rise to much angst when they happen.

- The robustness of pension sharing orders to changes in CEVs.

- Why we use percentages for pension sharing orders, not monetary amounts.

- The critical dates in the lifecycle of a pension sharing order (PSO).

I shall in this article consider all of these issues in turn.

The background, in brief, to the pension aspects of this judgment is as follows:

- In January 2023 Recorder Moys made a final order in the financial remedy proceedings between the applicant former wife (AFW) and the respondent former husband (RFH), following a three-day hearing in December 2022.

- In June 2023, a further hearing was held as the applicant alleged that the respondent was in breach of several of the provisions of the final order, including, inter alia, he 'refused to complete the pension sharing annex to enable implementation of the pension sharing order' that had been made in his favour. The PSO was for 49.2% of the wife’s NHS pension.

- At paragraph 95, it said: 'The respondent has claimed that there has been a freeze on public sector pension values and that there will potentially be a recalculation of the applicant's pension in the coming months. He says that until he receives clarity from the applicant about this, he is not willing to complete the documentation he is required to send to the pension provider to implement the order.'

- The PSO was made on 26 January 2023. The decree absolute was dated 23 September 2021, and thus, as Recorder Moys says in paragraph 96: 'The pension sharing order therefore took effect on 23 February 2023 (i.e. 28 days after the final order was made, this being "transfer day").'

- Towards the end of March, the NHS pension scheme, along with other public sector schemes, suspended the provision of CEVs and the implementation of pension sharing orders, pending a review of the actuarial basis underpinning the schemes, and the factors used to calculate both CEVs and the pension per annum to be granted for any given pension credit. The new factors were released in June 2023 and have been in use since, and thus an order can now be implemented.

- Recorder Moys gave the respondent until 28 July 2023 to complete the necessary paperwork to get the PSO implemented and return it to the applicant’s solicitor.

So let me turn to the statements I made at the start of this article as to the learning points of this judgment, and joining the first two, demonstrate why the worry or frustration from family lawyers, every time the public sector suspends provision of CEVs and in so doing frustrates the implementation of orders is misplaced, and just how robust a PSO is to changes in actuarial basis. To do this, I need to make some assumptions, as we know little of H and W in this case, other than W has an NHS pension. I am going to assume:

- W was aged 50 in January 2023, and is now aged 51, and H was aged 52 in January 2023 and is now aged 53.

- W had accrued in the NHS 1995 scheme, a pension of £15,000 pa, and a lump sum of £45,000, as at January 2023 which because we are assuming we are dealing with the NHS 1995 scheme, will be payable at age 60. I am assuming the pension is deferred (that is to say W is no longer actively accruing benefits). This being so, the pension benefits (pension and lump sum) will have increased by 10.1% in April 2023 (as would any pension benefits had a PSO been implemented in January 2023.)

On this basis, we can say:

- The CEV of W’s NHS benefits of a pension of £15,000 pa and lump sum of £45,000 in January 2023 was £300,600, using the old actuarial basis.

- The CEV now, of W’s NHS benefits, which due to the inflationary increase in April 2023 now stand at pension £16,515 pa and lump sum of £49,545, is now, in September 2023 using the new factors, £379,845.

As can be seen, the CEV from January 2023 to September 2023 has risen by 26%, due to (i) the new actuarial basis which has the effect of raising all CEVs, (ii) W being assumed to be one year older and (iii) the 10.1% increase in benefits in April 2023.

So what is the impact of a 49.2% PSO (the amount prescribed in Recorder Moys’ judgment in January 2023) using both the old and new CEVs? The following table sets this out:

| Comparison of PSO of 49.2% in January 2023 vs September 2023 | ||

| Date of CEV and assumed implementation of PSO | Jan-231 | Sep-23 |

| W's NHS pension per annum | £15,000 pa | £16,515 pa |

| W's NHS lump sum | £45,000 | £49,545 |

| CEV of benefits | £300,600 | £379,845 |

| PSO made | 49.2% | 49.2% |

| W's pension after PSO | £8,390 pa | £8,390 pa |

| W's lump sum after PSO | £25,169 | £25,169 |

| Pension credit awarded to H | £147,895 | £186,884 |

| Pension awarded to H in NHS | £8,037 pa | £8,172 pa |

| Lump sum awarded to H in NHS | £24,111 | £24,515 |

| Variance in W's outcome | 0.0% | |

| Variance in H's outcome | 1.7% | |

We can see that from W’s perspective:

- Had a PSO of 49.2% been implemented in January 2023, when the CEV was £300,600, then adjusted for the April 2023 pension increase, W would have been left with a pension of £8,390 pa and a lump sum of £25,169, which is the identical outcome for W had the PSO been implemented in September 2023 when the CEV was 26% higher at £379,845.

And from H’s perspective:

- Had a PSO of 49.2% been implemented in January 2023, from the pension credit of £147,895 (49.2% of £300,600) H would have been awarded a pension of £8,037 pa and a lump sum of £24,111 (again adjusted for the April 2023 increase of 10.1%) and had the same order been implemented in September when the CEV was 26% greater, and the pension credit thus £186,884, the outcome would be only marginally different (1.7% greater) with a pension of £8,172 pa and lump sum of £24,515.

In other words, the outcome for both W and H is not materially different whether the PSO of 49.2% had been implemented pre-NHS CEV suspension when the CEV was £300,600 or whether it was implemented nine months later with the new actuarial factors, despite the CEV having increased by 26% in the interim.

This is why I say in lectures and blogs and other articles, when dealing with public sector pensions, I am not usually as bothered as many others when we see these occasional revisions to actuarial bases. The reason we can usually be so phlegmatic about these public sector revisions, is because both member and ex-spouse remain in the same scheme, and any changes to the actuarial basis usually affect the member and ex-spouse equally.

This is not so where we see revisions in private sector schemes where the ex-spouse is required to take their pension credit out of the scheme. Great care needs to be taken where we see revisions (like the very significant reductions we have seen in the last 12 months to private sector final salary CEVs) unless that scheme allows internal implementation. Even then, I would want to satisfy myself on this point, prior to proffering an opinion upon which the parties / court rely.

We can also see here why the PSO legislation requires a percentage to be stated, not a monetary amount. The above example shows just how robust PSOs (if they are expressed in percentage terms) are to changes in CEVs. Let’s assume, though, that instead of stipulating a PSO of 49.2%, it had been stipulated that H should receive a pension credit of £147,895 (which is the effect of a PSO of 49.2% based on the January 2023 CEV).

- Well, had such an order been made and implemented in January 2023, the outcome for the first numerical column would be the same as above – a PSO of 49.2% and pension credit of £147,895 are interchangeable as long as the CEV is £300,600.

- The second numerical column (assuming the order is made in September 2023) would change dramatically. The requirement for H to receive a pension credit of £147,895, would have necessitated, with the new CEV of £379,845, a PSO of 38.9%, with the result, as we can see summarised in the table below, that W would be c. 20% better off and H c. 20% worse off than had the order been implemented in January.

| What would have happened had the January order specified a pension credit of £147,895 (49.2% of the January CEV)? | ||

| Date of CEV and assumed implementation of PSO | Jan-23 | Sep-23 |

| W's NHS pension per annum | £15,000 pa | £16,515 pa |

| W's NHS lump sum | £45,000 | £49,545 |

| CEV of benefits | £300,600 | £379,845 |

| PSO made | 49.2% | 38.9% |

| W's pension after PSO | £8,390 pa | £10,085 pa |

| W's lump sum after PSO | £25,169 | £30,254 |

| Pension credit awarded to H | £147,895 | £147,895 |

| Pension awarded to H in NHS | £8,037 pa | £6,467 pa |

| Lump sum awarded to H in NHS | £24,111 | £19,400 |

| Variance in W's outcome | 20.2% | |

| Variance in H's outcome | -19.5% | |

Instead of prevaricating over the order, H should be thanking the people responsible for the pension sharing legislation!

All of this demonstrates in clear monetary terms, the points raised by HHJ Hess in T v T (variation of a pension sharing order and underfunded schemes) [2021] EWFC B67 and that of Mrs Justice Baron in H v H [2010] 2 FLR 173 where to counter the effect of moving target syndrome, a PSO should be 'specified only in percentage terms'.

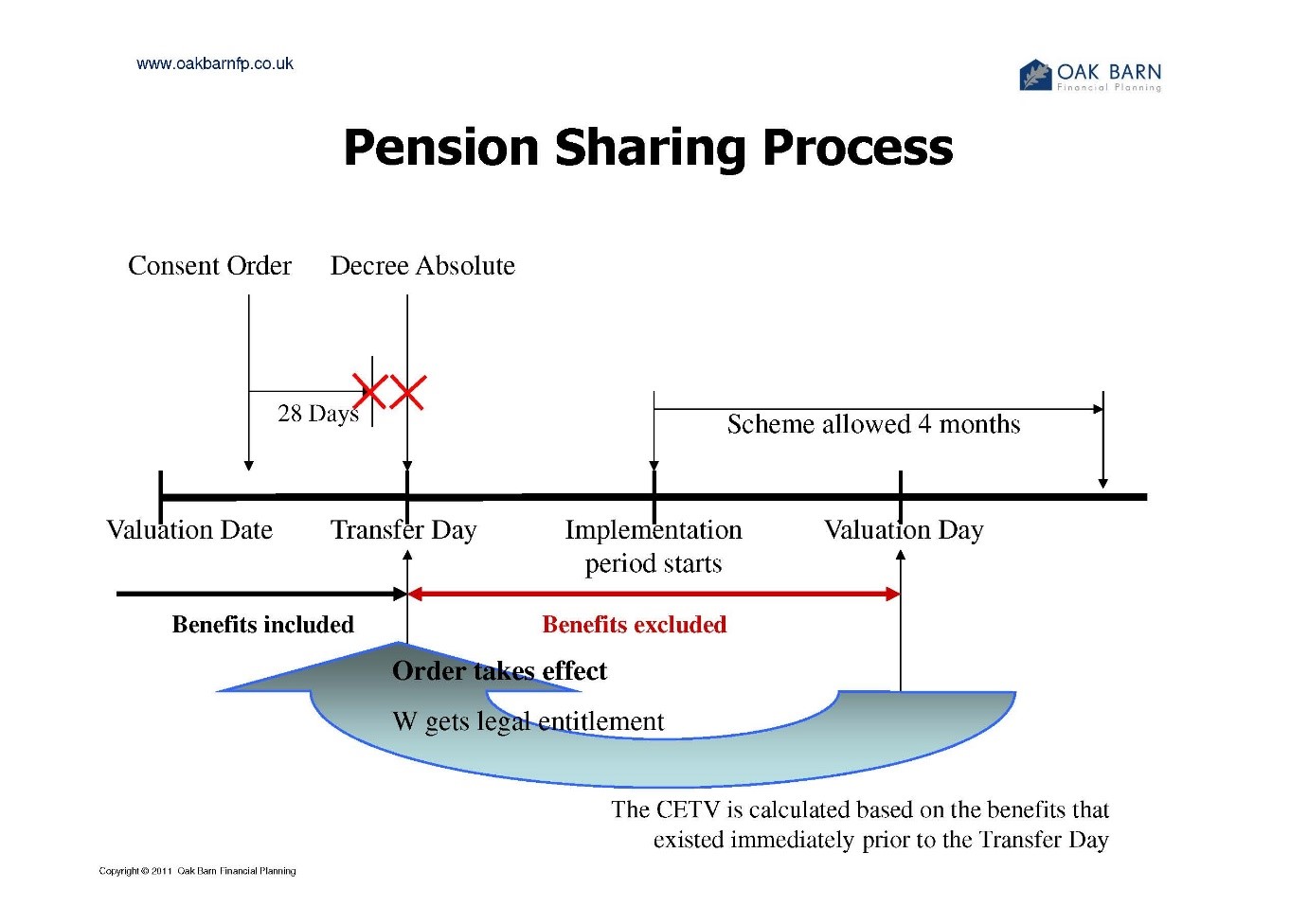

I think we should also be most grateful for Recorder Laura Moys setting out most clearly the issues around dates. Paul Cobley of Oakbarn Financial Planning produced the following diagram some years ago which sets out a summary of the key dates very well:

What is both gratifying and at the same time worrying, is that whilst Recorder Moys sets out the legislation regarding dates very well, the NHS Pensions Agency appears not to understand the legislation. At paragraph 97 says:

‘The applicant has produced a letter from her pension scheme provider that states, “As the PSO was finalised on 26th January 2023, the order effective date is 28 days after this date and therefore the CETV which you have received will not be affected by the change in factors.”’

This I believe is incorrect, because as Recorder Moys correctly says in paragraph 101:

'As the order has already taken effect, in any recalculation on the "valuation day" the provider will take into account market fluctuations but not any additional pension contributions (or drawdown) made by the applicant in the intervening period between transfer day and implementation.'

The revision of the CEV is exactly what 'market fluctuations' is referring to, and thus should be taken into account. This is perhaps a nugatory point of academic interest only, because as we show above, the fluctuation in value is neutral.

One further point, and for this I am grateful to the eagle eyed Paul Cobley again, he notes that at paragraph 106 Recorder Moys states:

'If the respondent refuses to provide information that is in his possession (such as his national insurance number) which is not currently known by the applicant/the court then the practical effect will be that the pension sharing order cannot be implemented and he will not receive any pension payments. I had initially considered that – given the effect of non-compliance by the respondent would be prejudice to the respondent and not the applicant – there was little the court could or should do about this state of affairs.' (Emphasis added)

There are circumstances where non-compliance by H (the respondent and recipient of the PSO) would be prejudicial to the applicant wife. For example, if during the period of non-compliance W had retired and drawn her pension, and H then remained non-compliant for a long period, potentially W could face a significant clawback of pension deemed to be overpaid by the scheme.

It should also be noted that – as Rhys Taylor so eloquently states in his article – thanks to paragraph 95 b iii of the new Standard Family Order Template, when it comes to frustrating a pension sharing order:

'The coercive controller will be wise to resist his (for it usually is the husband) darker impulses as such behaviour will now put him on the wrong side of a court order, whereas before he could act with apparent impunity.'

Conclusion

This seemingly simple judgment of Recorder Moys, on an application to force compliance with previous orders, may sneak under the radar of many. But it is such an elegant judgment for us pension experts, in that (i) it enables us, in a real case, to demonstrate why PSOs are expressed as percentages and the robustness of such an approach, and (ii) it sets out in such clear terms all of the critical dates in the lifecycle of a pension sharing order. I commend it to all as a Primer on Pensions and Divorce.

George Mathieson is not a FCA regulated person, and thus is not able to advise individuals on matters covered by the FCA regulation. Any guidance that George Mathieson supplies is not covered by those protections available for the regulated activities of RBC Brewin Dolphin; including access to the Financial Services Compensation Scheme and the service of the Financial Ombudsman Service.

Risk warnings

The value of investments, and any income from them, can fall and you may get back less than you invested. This does not constitute tax or legal advice. Tax treatment depends on the individual circumstances of each client and may be subject to change in the future. Information is provided only as an example and is not a recommendation to pursue a particular strategy. Opinions expressed in this publication are not necessarily the views held throughout RBC Brewin Dolphin Ltd. Information contained in this document is believed to be reliable and accurate, but without further investigation cannot be warranted as to accuracy or completeness.

RBC Brewin Dolphin is a trading name of Brewin Dolphin Limited. Brewin Dolphin Limited is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority (Financial Services Register reference number 124444) and regulated in Jersey by the Financial Services Commission. Registered Office; 12 Smithfield Street, London, EC1A 9BD. Registered in England and Wales company number: 2135876. VAT number: GB 690 8994 69