Arbitrating Costs Provision Applications

Published: 05/12/2024 08:00

There have been few seismic changes in family law that reshaped everything. Much as we would love suddenly to have a new landscape for our professional work, most of us can only hope to find small solutions that work for some small corner of one field. However, bit by bit this may all contribute to an evolving and improving climate in which families change and start their new chapters. Here we hope is one more such.

One feature in that vista is that separating partners generally need advice and support to reach good agreements and oftentimes, one party has access to the funds for advice and the other does not. In the absence of agreement and co-operation an intervention will be needed, without which there cannot be fairness in the litigation or negotiations, in other words a level playing field.

We are conscious that there is a difference between:

- the matrimonial situation where one party is simply seeking access to the resources in which they are entitled to share; and

- the Schedule 1 case, where the applicant is seeking provision for their child out of the respondent’s resources.

We anticipate that in time these differently nuanced case-types will (and should) lead to different jurisprudence. We do not explore that aspect here. This article asks the question, ‘in the light of PD 9A, can’t we do these cases a little bit better?’

Problems with fees funding applications

Litigation funding as we have all experienced comes at a price and with difficulties. The LASPO solution is not a cure all; there is an immediate bind:

- Court dates are hard to come by and involve long waits.

- The court is reluctant to provide for payment of historic costs (which are inevitably incurred in the preparation of the application, and in progressing the case and/or dealing with interim issues pending the hearing).

- The process designed to address the question of costs actually exacerbates them as it comes at significant expense for both parties.

It is not helpful that the case has to stall until the court date arrives. Families move on and waiting months for the hearing that may then provide the funding – or funding but not enough of it – is far from ideal. In cases where there is an abusive dynamic, the financially stronger party may use the delay to their advantage knowing the absence of funding is placing the other party under strain.

Quantification of the claim

Then is the issue of the automatic assessment of costs:

- 15% in BC v DE [2016] EWHC 1806;

- 30% in X v Y Re Z (No 1) [2022] EWFC 80 at [39];

- Confirmed again in May 2024 as 15% in JK v LM [2024] EWHC 1442.

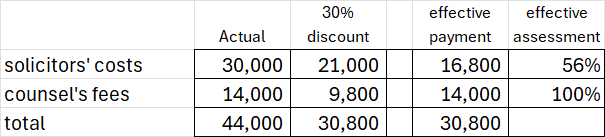

Just pausing to reflect on this point, how this may play out could be particularly challenging for solicitors. Many counsel are generous about their fees. However, if you take the view that it is solicitors who take on the case and counsel who are appointed under a cab rank rule, then it is not for counsel to assist with the funding of the case. If they are paid in full then, the quasi-assessment falls disproportionately on the solicitor. For example:

We don’t understand why, when the purpose of the application is to provide access to justice and a careful assessment as to the likely spend has been carried out, that there is then a mechanical deduction below that figure, particularly where the other party is left free of such restrictions.

This is why the alternative approach is so welcome

- In DR v ES [2022] EWFC 62 (a judgment that appeared March 2023, although delivered in 2022), Francis J said at 59:

‘Mr Hale, on behalf of the husband, made the very valid point that when one goes through an assessment of costs, you get about 30 per cent knocked off. Well, that may be true in civil litigation, it may be true where one party is ordered to pay the other's costs in some family litigation, but my job at the moment is not assessing costs in that sense of somebody being made to pay an order for costs, it is dealing with debt. The wife's debt to her solicitors is a debt that she has to pay, and if she does not pay it, there is a serious risk that they will not continue to act. There is no reason why solicitors should act as creditors or bankers to litigants, and many firms are unable or unwilling to do so, particularly when the numbers are in six figures, as they are here.’

- Peel J took the same approach in HAT v LAT [2023 EWFC 162 from [34] onwards:

‘34. In my judgment, a LSPO should be made in order to level a playing field which would otherwise lean heavily in H's favour.

35. I considered applying a notional reduction to reflect what would occur on a standard basis assessment, a technique which has on occasions been used by judges of the Division (see, for example, Cobb J in BC v DE [2016] EWHC 1806 (Fam). But on balance my view is that to do so would be the wrong approach in this case. This is not an inter partes costs order where such a deduction is routinely applied. It is a solicitor/client sum sought by W to enable her to litigate in circumstances where she cannot reasonably be expected to access her own limited resources.

36. The approach to quantum, in my view, is simply whether the costs sought are reasonable, in the context of the nature of the litigation, the issues, the resources, and how each party is approaching the proceedings …’

Until these two approaches are reconciled, it adds uncertainty of approach to an already unpredictable domain.

Still, this is our law (or these are the two approaches in our law) and until changed that is what must be applied. Perhaps the biggest challenge is that the applicant (‘party A’) only gets their case off the ground at all if they can persuade a lawyer to carry out the preliminary work and run the risk that they are not paid for it. For most firms with any sort of commercial interest in staying in business, the message may well be clear:

- Monied parties? ‘This way sir.’

- Parties A? ‘Let me provide you with a list of excellent law firms for you to call.’

Not a great outcome for a system that holds at its heart the 'equality of arms'.1

Other problems with our law

Fast forward to the costs application itself and the court awards a sum of money for party A to litigate the case to an FDR. Irrespective of the sum ordered, we might see a strange version of the level playing field:

| The monied party (‘party B’), generally has: | Whilst the applicant for provision (‘party A’) may: | |

| 1. | Freedom of choice of lawyer. | Immediately following the LASPO hearing party A might find themselves without a lawyer because: (a) the court has reduced party A’s budget to such an extent that the solicitor cannot do the necessary work within the budget; and/or (b) the court refused to order that party B pays the full costs party A incurred in making the application, and the solicitor’s firm’s credit policy might not permit them to work whilst carrying an unpaid debt on their file. Realistically this debt could be unpaid on the file for the next 12–18 months (or however long it might take for the case to the resolved, and for party A to receive an award from which the debt can be paid). |

| And those lawyers and the client enjoy: | If party A’s lawyers are willing to take on the case, they will have to contend with: | |

| 2. | No need for costs estimates to the court or other side going forward. | Being stuck with an inflexible estimate which operates as a fixed fee. |

| 3. | No containment on hourly rate. | The inability to increase hourly rates during the LASPO. |

| 4. | Freedom to manage the case strategically and flex spends on fees as required. | The litigation strategy being substantially limited by the imposed budget, creating a potential conflict between party A and their lawyer. |

| 5. | Costs usually paid in full on the usual ‘as you go’ basis. | Having historic costs paid only if there is evidence that otherwise the applicant will not be able to access representation (X v Y re Z [2020] EWFC 80). |

| 6. | Freedom in case and costs planning. | Having to repeat an application after FDR; and the need for party A’s solicitors to undertake all the work that immediately follows the FDR order on credit. |

| 7. | No scrutiny applied with regards to the way a funded litigant uses their legal spend. | The possibility that provision may be refused if:

|

The incentives to enter NCDR

Is there a solution?

Well, ‘of course’ to at least part of it. We trailed that in our opening paragraph. We take a leaf out of PD 9A, which surely creates the expectation/default that where safe, unresolved disputes will generally find their resolution in arbitration (see paras 17a & 25(v) for example.)

In our view, generally, these cases should not be troubling the court at all.

Party A will welcome the new procedure: quicker and cheaper will help a lot.

Party B will refuse at their peril. Surely properly directed, the court would say in terms:

‘You had a chance to sort this out 3 months ago

So how can you fairly complain about Party A incurring historic costs during this period?

Had you taken up this offer to arbitrate, this, it would have all been completed at a fraction of the cost and on papers. And perhaps as importantly, it probably could have been a conversation between solicitors (who, after all are the ones with expertise in formulating costs estimates) rather than involving another layer of professional fees through [no disrespect to their value] counsel.

So regardless of the award I am about to make, it is right that party B picks up the additional costs of this process.’

Party B will also reflect that starting on that (likely) footing is no safe way for them to enter a discretionary exercise. It is this norm that should provide the incentive to respondents to requests for funding (parties B) to enter this NCDR process: they will do so because of how it may affect their case if they do not. The upsides for the court and for society’s aspiration to fair outcomes is promotion of somewhat fairer litigation and a small contribution to reducing the queues at court.

A procedural route map – the LASPO arbitration protocol

We see arbitration running on fixed tracks with a tested process at relatively minimal cost and with minimum delay (the possible directions are in the panel below) – where the process can begin immediately the need is identified:

| For example | |

| Party A proposes adopting the costs provision protocol and provides the form ARB1FS (‘the commencement date’). | Jan 1 |

| Party B signs form ARB1FS within 7 days. | Jan 8 |

| Party A sends the signed arbitration form to: | |

| - the agreed arbitrator; or | |

| - to IFLA to select an arbitrator marked URGENT seeking a selection within 7 days. | Jan 15 |

| Within 3 weeks of the commencement date, the parties provide each other with: | |

| - Their signed terms of business with their lawyer; | |

| - A detailed cost estimate; | Jan 22 |

| - An account on spending on lawyers to date; and | |

| - The standard information required in the Rubin run of cases (if not provided already). | |

| Within 14 days party B indicates: | |

| - whether they agree Party A’s cost estimate and if not, their reasons for this; and | Feb 5 |

| - whether they are prepared to adopt matched funding. | |

| Without prejudice save as to costs offers might be made at this stage. | |

| The parties then provide written submissions to the arbitrator, with party A providing theirs within 7 days of Party B’s indication of their provision and Party B providing theirs 7 days later. | Feb 12 Feb 19 |

| Party A may reply only to new matters arising within 3 days. | Feb 22 |

| Adjudication on paper within 7 days. | Mar 1 |

Incidentally, it is a short step from considering the steps and stages to giving directions in the case and one could see the benefits of this process becoming the entrée to the arbitral process, with its benefits of faster, cheaper and more focused resolutions.

Conclusion

We acknowledge that this does not immediately solve all of the problems set out in the first table but in arbitration it is the law that must be applied, rather than the arbitrator’s view of what the law ought to be. In addition, the benefits of a decision being secured more quickly and cheaply are significant – as is the benefit of the opportunity for considered and expert input. As we said at the start, greater change may come through incremental steps and solutions for specific situations. We leave the issues in the first table to others for now.